ROSES ARE RED, VIOLETS ARE BLUE,

ME LUVLY TEACHER, I BELIEVE IN YOU.1

1. Introduction

Early debates on the invisibility of women in Yugoslav history were initiated as late as the mid-1980s2 and the greatest contribution to the promotion and strengthening of feminist historical research of autonomous women’s organisations and associations was made by the late Lydia Sklevicky, the feminist theorist who left us too soon.3 In her work4 she consistently criticized the traditional approach to the ‘grand topics’ of political, military and diplomatic history, and stood up for the research and analysis of historical change in everyday life, the relationship between sex and gender, and the writing of a (new social) history of women.5

Although the second half of the 1980s was marked by feminist-orientated works,6 and a renewed interest in women’s issues,7 this positive trend in research was brought to a halt by wartime8 as well as post-war socio-political developments and cultural and educational policies. The questions of the AFŽ’s legacy and/or the emancipation of women in the People’s Liberation Struggle (henceforth NOB) and during the socialist period were considered anew from a feminist point of view as late as the beginning of the new millennium.9 In this regard, a phenomenon of particular import is the emergence of a new generation of women scholars, in the region and beyond, who have explored, for their master’s and doctoral theses, certain aspects of women’s engagement in the NOB and the AFŽ.10

Although Bosnian-Herzegovinian historiography still does not indicate that an institutional framework for the systematic study of the modern history of women will be established in the foreseeable future,11 it should be pointed out that the establishment of the online Archive of the Anti-Fascist Struggle of Women of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Yugoslavia12 has been a significant step forward in the archiving of materials13

pertaining to the engagement of women in the NOB and the AFŽ, if nothing else.14 The archive makes it possible for new generations of female scholars and researchers as well as artists and cultural operators to conduct research15 and offer new answers to questions related to the unfinished processes of emancipation and participation of women in the political, cultural and educational life of the community.

Thanks to the invitation extended to me to participate in the production of a publication which aims, among other things, to affirm the Online Archive, I received the opportunity to explore, to an extent at least, a prominent revolutionary figure – the progressive people’s teacher, or more precisely, her role and tasks in the revolutionary activities and the establishment and construction of the new social order. Despite the fact that people’s teachers garnered enormous respect and admiration in BH society, they mostly remained timeless heroines, symbolical figures, “anonymous accomplices, fellow travelers, fellow fighters, associates”, most of whom have yet to go down in history “with their full names and surnames, with their roles, functions, thoughts, feelings, hopes and fears.”16

To demand that they be recorded in history, together with all the other forgotten, neglected or erased figures of women workers and revolutionaries from BiH, is the only way to break the “endless circle of discovering and forgetting women’s history, emancipation and oppression, from the endless restoration of the patriarchal order of values and relations which becomes more and more ruthless in every subsequent historical episode.”17

1.1 The Framework and the Aim of the Paper

Even though many researchers18 in our historiography have explored the topic of the historical development of BiH school system from the Ottoman period to the end of WWII, relatively little19 has been written about the characteristics of the teachers’ professional activities and their contribution to the social and cultural development of the community. Although there had been trained teachers in BiH as early as the end of the 18 century, and even though they left a deep mark on the development of culture as such, Mitar Papić notes that “this was written about only sporadically […] and we still do not have a single synthesis which would show that we have never had a profession in BiH whose contribution could bear comparison to that of the teaching profession.”20

However, none of these sporadic notes written before the 1990s specifically examined the status and the social role of female teachers or their contribution to the development of the school system in BiH. Moreover, although it was precisely the teachers who championed the establishment of professional associations (as early as 1896, Marija Jambrišak and Jagoda Truhelka called on teachers to unite along class lines, which was realized with the formation of the Teachers’ Club in the reading room of the Croatian Teachers’ Hall in Zagreb in 1900).21

Jovanka Kecman, in a study devoted to working and professional women’s associations, deals with the status of progressive teachers in the 1930s by examining their activities solely as part of the progressive teachers’ movement and the activities of the Communist Party.22 That is to say, the information on specific aspects of the teachers’ activities remained rather fragmentary, and was mentioned in passing in papers which treated the broader topic of education, or the teachers’ movement. The trend continued after the 1990s war, with only a handful of papers dealing to an extent with the education of women in the BiH school system or with prominent female educators and cultural figures from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.23

Like most topics related to the socialist heritage, the topic of the progressive teachers’ movement is either neglected or mentioned only in passing in general overviews of the development of the teaching profession in BiH, and not a single monograph on progressive women teachers has been published hitherto. But, as I attempt to demonstrate in this paper, it is precisely in the figure of the woman teacher that all the contradictions of becoming the new working woman in socialism are inscribed. At the same time, having become the possessor of an aversive excess of memory24 of socialism and anti-fascist struggle in the aftermath of the war in BiH, the figure of the (progressive) people’s teacher can also point to possible alternative models of thinking the present moment, marked by processes of faux emancipation and aggressive repatriarchization of women.

The paper examines the role and position of the (progressive) people’s teacher from the late 1930s to the early 1950s, considering this to have been a crucial period of comprehensive transformation of the state-operated system of mass primary education in which the new type of teacher was constructed. The figure of the woman teacher is especially indicative in this regard. The process of the formation of a new type of teacher builds on the effort to completely change the social position of women25 and create a new type of woman26 in BiH27 first via Party edicts during the NOB, and subsequently via constitutional and legal solutions.

Assuming that the educational system can be seen as a tangle of discourses, knowledge, legal and institutional arrangements of the ruling regimes and social structures that for a long time had ensured and legitimized first the exclusion, then the discrimination of women in education and teaching, this period is interesting because it was precisely during those twenty years that the number of primary school women teachers soared. At the same time, female teachers were officially made equal to their male colleagues; the new government provided equal living and working conditions and – nominally, at least – strove to improve the traditionally unfavorable financial circumstances of teachers.

The intention behind this paper is to outline the numerous social duties of the teachers during the NOB, first and foremost in spreading literacy and educating women to meet the needs of the general mobilization during the NOB, and their selfless, committed work on raising and educating children and spreading literacy among adults over the first few years following the liberation of the country as part of the five-year reconstruction plan. The main goal of the paper is to trace the trajectory of the progressive teacher from a revolutionary figure forged in the struggle for a new, more equitable social order to a figure that is gradually depoliticized and rendered passive, as part of a wider process of feminization of the teaching profession.

2. Material Conditions of Work and the Administrative and Legal status of Female Teachers During the Austro-Hungarian Occupation and the Interwar Period

Ever since the beginning of the development of a (state-operated) school system in BiH, 28 which dates from the early days of Austro-Hungarian rule in this country, female teachers, as civil servants, had to work in accordance with markedly discriminatory public service laws and by-laws which greatly contributed to the deterioration of the working conditions and advancement opportunities for female teachers.

In spite of the increase, compared to the Ottoman period, in the number of female primary schools, as well as female teacher training schools,29 the Austro-Hungarian authorities did not actually strengthen the processes of female emancipation, nor did they think it was in their interests to increase the number of women in public service. As Suzana Jagić writes, in the Austro-Hungarian period, alleged bodily and spiritual differences between the sexes were used as a pretext for different approaches to the education30 of women and men, and for their different positioning in society.31

Thus in this markedly patriarchal society32 women, as “lesser beings”, were not only assigned different roles and tasks, but their freedom to operate in the public sphere was limited too. The public service, as a potential arena for the engagement of women, did not approve of the hiring of women, as it was considered that women belonged in the private realm of the home where their chief roles included those of homemakers, wives and mothers. Thus women were hired as public servants almost exclusively in the field of education.

Although the number of female teachers was constantly rising, Austro-Hungarian authorities did nothing to create a legal framework which would ensure the improvement of the professional and material conditions for women teachers. On the contrary, the Act on the Rights and Relations in the Teaching Profession subjected women teachers to multiple discrimination. In addition to their salaries being lower than those of their male colleagues, and their advancement made more difficult by the so-called pay grades, they were not allowed to marry; that is, if they did marry, they would be permanently banned from teaching. An exception was made for marriages to male teachers, in which case the female teacher’s salary would be halved and she would lose the right to paid accommodation and other employment benefits.33

All female teachers graduated from teacher training schools before they turned seventeen, but many would start working as teaching assistants at fifteen or sixteen. As a rule, after graduation, they would be posted to female primaries. They were allowed to work at male primaries only if there was a shortage of male teachers, and could only teach junior years. They would win the right to teach at secondary schools only in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. As for advancement and pay grades, the process was very slow, and women would, at best, reach pay grade three towards the end of their careers. Thus, for instance, teacher Hasnija Berberović took her first teachers’ oath in 1909, and her last in 1934. She spent 29 years teaching, and was retired in 1939 for health reasons, but, as Mina Kujović points out, it is questionable whether this hard-working teacher was able to enjoy her well-deserved pension of 1475 dinars, seeing that she was committed to a mental hospital, and her pension was deposited with the court.34

Even after the breakdown of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), there was no significant improvement in the financial circumstances and working conditions of women teachers. The problems faced by teachers remained the same in the newly-formed kingdom; teachers still lived in financial hardship, which is best illustrated by their excessive debts due to extremely low salaries35 recorded in some banates, as well as a large number of resolutions on the issue adopted all over the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.36

Teachers who championed the cause of progressive education37 and were active in the Communist Party of Yugoslavia,38 or openly supported the Party were at best transferred to other banates or subjected to frequent controls, arrests and protracted trials; some spent years in prison, including a number of female teachers. For instance, teacher Lepa Perović, a distinguished Party activist, was arrested for revolutionary activities and transferred from Bosnia to Serbia, only to be fired from public service in 1937. Teacher Draginja Savković spent three months in remand before she was arraigned and charged with spreading communist ideas and propaganda, but the charge was dropped due to a lack of evidence. After the trial she remained under constant police surveillance, and was transferred to another county.39

Persecution and arrests continued during World War II. Ilinka Obrenović-Milošević, known as the Red Teacher, was pregnant when she was arrested for collecting food and clothes for Partisan fighters and deported to the Banjica concentration camp. A similar fate befell the progressive teacher Živka Vujinović-Bula, who spent eleven months in the Banjica camp, and was fired from her post upon release.40

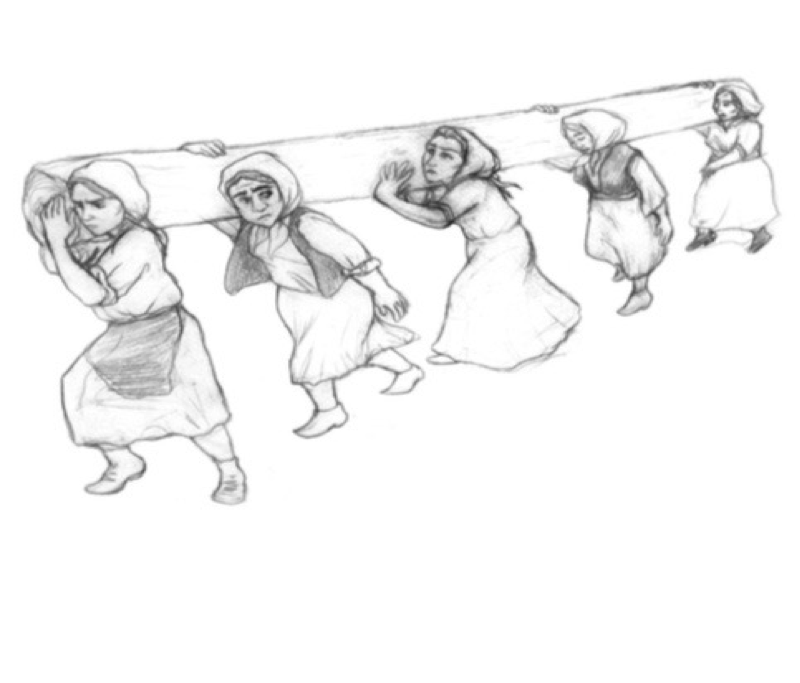

In addition to the legally mandated rights and obligations, the profession faced specific problems in the teaching process itself as well as in extracurricular activities in the community, especially where the population was largely illiterate. This was usually the case in rural areas. Working in the country was much more difficult because rural school buildings often did not meet the most basic of requirements for work, and instruction was, as a rule, organized in a single classroom. Jovanka Kecman notes that female teachers were mostly employed in the country after they graduated from teacher training schools. In addition to their work at school, they had the obligation to participate in the activities of all cultural organisations and charities operating in their counties, as well as to organize literacy courses and housekeeping courses which educated women on the importance of hygiene, a healthy diet and household economy. In spite of their much greater workload, female teachers were underpaid – in some cases their salaries were up to 50% lower than those of their male colleagues.41

3. The Development of the Progressive People’s Teacher on the Eve of World War II and During the People’s NOB

On account of their social engagement in the country, women teachers enjoyed a good reputation among the villagers and were influential in the community, all the more so because they respected local customs, lived by the village rules and were therefore treated as full members of the community. For this reason, the Communist Party, having strengthened and massified the progressive teachers’ movement, would lay particular stress on training female teachers for so-called political work in the rural areas.42 Since young teachers received their first posts in villages and towns as a rule, the political mission of the progressive teachers’ movement focused almost exclusively on these rural areas.

Seeing that the CPY operated illegally from 1921 to 1936, their legal activities among teachers took the form of starting culture and publishing collectives. The progressive teachers of BiH started their own “Petar Kočić” collective as late as August 1939, at the Teachers’ Congress43 held in Banja Luka, having previously operated through the “Vuk Karadžić” and “Ivan Filipović” collectives. These collectives organized gatherings of teachers, where the so-called Pedagogy Weeks, organized during winter holidays between 1938 and 1941, were especially important, as political and ideological lectures were held and discussions on important issues and problems of the profession.44 From 1936 onwards, the activities of these collectives, and their work with progressive female teachers were especially intensified.45 In addition to these gatherings, progressive teachers developed their political, cultural and educational activities through people’s libraries and reading rooms.46 Of the several magazines they published, Učiteljska straža (Teachers’ Guard) was of particular note.

Since progressive teachers were mostly assigned to villages, they became the core membership of the Communist Party in rural areas; more specifically, in Bosnia, we are talking about villages in Bosanska Krajina, areas around Sarajevo, Mt Romanija, Semberija, and East Herzegovina. It was in these areas that most teacher-WW2 volunteers, recipients of the 1941 Partisan Commemorative Medal, lived and worked.47 Whilst the authorities in the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina administrated by the Independent State of Croatia (ISC) were committed to creating a new state-run education system, Croatian in character, by endeavoring to “[…] breathe into its first laws the ‘ustasha spirit and the Croatian national spirit’ […] in the spirit of anti-Semitic policies accompanied by racial laws”,48 the leadership of the People’s Liberation Movement (NOP) endeavoured to implement the CPY programme and the NOP Platform from the very beginning of the uprising, and worked on developing and improving popular enlightenment schemes by running literacy programs on a massive scale and renewing and developing the regular education system in the aforementioned (free) territories.49

According to a report by the teacher Mica Krpić, organized work in education commenced as early as April 1942 in villages around the town of Drvar, where the first cultural and educational committees were established along with literacy courses with classes three times a week.50 Cultural and educational work spread over Mt Kozara and the villages of the Podgrmeč region, where literacy courses were led by, among others, teachers Mica Vrhovec, Ivanka Čanković, Jela Perović and Anka Kulenović.51 After that, educational departments were established to organize courses preparing young people for work in schools and literacy courses. In addition, teachers Nijaz Alikadić and Cecilija Čebo wrote the first textbook for pupils, the Primer of Livno (Livanjski bukvar).52

After the First Session of the Anti-Fascist Council of the People’s Liberation of Yugoslavia (Antifašističko vijeće narodnog oslobođenja Jugoslavije – AVNOJ) which took place in Bihać in late November 1942, the Educational Department of the Executive Committee of the AVNOJ was tasked with organising educational activities in the liberated territories. The Department adopted a series of regulations, including the Instruction on Primary School Work, along with a number of requests and instructions to Narodno-oslobodilački odbori (NOO) to open new primary schools and literacy courses, as well as syllabi for primary schools, courses and the people’s university.53 Kožar argues that these documents of the Educational Department are “an historically significant clue for the reform of education in the spirit of the ideology of the NOP’s forces. They mark a new era in the development of schools.”54

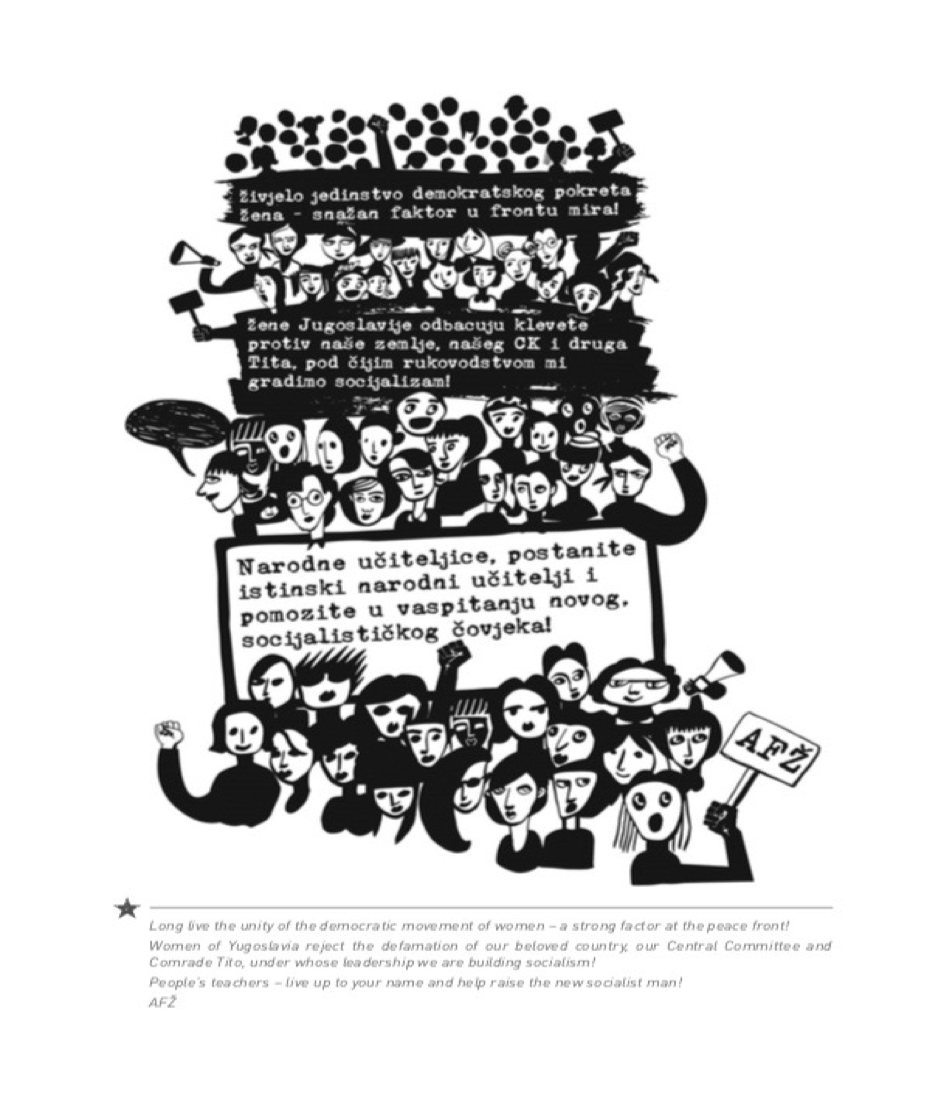

From late 1942 onwards, conditions for organizing literacy courses in the free territories as well as in the Partisan units were improving, largely thanks to the empowerment of the AFŽ as a mass political organization.55

In addition to the courses for literacy course leaders, the AFŽ also organized political education courses for women, regionally and nation-wide. Lectures were given by, among others, Mara Radić, Nata Hadžić-Todorović (in the region of Bosanska Krajina) and Radmila Begović and Milka Čaldarević (in Eastern Bosnia). The AFŽ also set up culture groups comprising poetry recitation sections, event organisation sections, and sections for reading radio news and Partisan press.

In November 1943, the AFŽ organized the First Educators’ Conference in the free territories on the topic of literacy courses and drafting a comprehensive primary school primer.56 Zaninović notes that a new groundwork was laid for the organisation of literacy courses with the liberation of large tracts of territory, while from 1944 onward it was compulsory for the courses to last 30 days with classes four times a week.57 The end of 1944 saw the beginning of a large-scale process of setting up new schools in the liberated territories.

However, the spreading of the network of primary schools and the rise of other forms of educational activities put the issue of staffing on the agenda. Just before the war, there were 1043 primary schools in BiH employing 2,321 teachers instructing 150,783 pupils, that is, 65 pupils per teacher.58

At the end of the 1944/45 school year there were 577 schools with 82,705 pupils, 359 male teachers and 741 female teachers.59 Given that, according to incomplete data, 173 male teachers and 80 female teachers were killed during the war,60 it is clear why restaffing was to become one of the key challenges of the new educational policies.

As a temporary solution, the decision was made to start training temporary teaching staff while the war was still on, to have them fully trained after the war. Teaching courses were set up and all young people who had completed at least two years of secondary school were invited to enrol. The first course was carried out in Sanski Most in May 1943. Another was then held in Lipnik, and by the end of the war courses with the same syllabus were organized in several other towns in BiH. Most attendees graduated from teaching schools and universities after the war and became the vanguard of new educational policies in BiH.61 It should be pointed out that seminars were organized for new teachers and those who joined the movement and the NOB at a later stage, in which they were acquainted with the goals of the NOB and the educational policies implemented by the People’s liberation committees, as well as with the basic ideas of the progressive teachers’ movement.62

Thus, in addition to the progressive female teachers who started their revolutionary struggle in the interwar period and became prominent political and revolutionary figures,63 another type of people’s teacher emerged during the war: a young woman who had completed a few years of secondary school and had voluntarily joined the struggle, or had become a fellow traveller. These women were trained for teaching in courses started during the war. As a rule, they went on to graduate from teacher training colleges and continued to work in education until retirement.

3.1. Five Year Reconstruction Plan: New Challenges and Old Burdens for the Teachers

Educational policies of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia led to an illiteracy rate of around 75% in BiH in 1941. This undesirable situation was exacerbated by terrifying material and human losses, and thus after the war BiH faced enormous illiteracy rates, especially among women,64 as well as a lack of professionals, especially in education, and a large number of destroyed or damaged school buildings.65

This slowed down the planned tempo of the reconstruction of the country set down in the Five-Year Plan,66 which is why the improvement of education was one of the priorities of the new Yugoslav and Bosnian-Herzegovinian government. It was necessary to reconstruct damaged schools and build new ones, as well as educate new teachers.

At the same time, the newly-formed socialist state and the CPY had specific expectations from teachers.67 Among other things, in the first years after the war, the process of construction or reconstruction of institutions of culture went in parallel with the construction and reconstruction of schools. Libraries and reading halls were opened, along with co-operative halls and culture halls. All these institutions were mainly managed by teachers, often without any kind of compensation. All of this made the teacher’s job extremely difficult in the first post-war years. However, in this period primary schools were in the focus of the state and socio-political organizations, which fired the teachers’ enthusiasm.68

I will now make use of the testimonials quoted below to try to roughly sketch the extremely difficult working conditions the people’s teachers were facing, but also their unquestionable enthusiasm.

First, one should mention the literacy courses, that is, one of the most important, most massified social actions of the day – the so-called literacy campaign. In five popular enlightenment actions carried out from 1945 to 1 October 1950, 42,196 literacy courses were organized and 670,874 people were taught to read and write.69

The people’s teachers’ contribution was enormous,70 since the courses ran under their supervision. Teachers taught 3,099 courses along with regular monthly or fortnightly counselling with course leaders to ensure highest-quality work. As Papić stresses, “enormous effort and overtime work were woven into [this undertaking], because every teacher taught, in addition to the courses, one or two classes at a regular school. The work started early in the morning and finished at night.”71 This is how teacher Slavica Bureković from Sarajevo, who served in the village of Pokrajčići near Travnik, described her experience of organising and leading literacy courses:

Teachers were tasked with spreading literacy, that was one of the biggest steps society was to take. There were very many illiterate people indeed, among them great numbers of young men and women. We teachers organized literacy courses even at come-togethers. The instruction usually took place late at night, when the teachers were free, after their classes at the regular school. I brought many women to literacy, I reckon seventy per-cent of attendees were women. I organized these courses not only in my home, but also in hamlets. On a few occasions I was remunerated for my work.72

Krunoslava Lovrenović, a teacher from the village of Ričice near Zenica, recounted that the courses were organized in winter months, from late October to late March or early April. They were mostly

organized late at night, because we teachers worked with regular pupils during the day. At times we didn’t have enough paraffin [for the lamps] and we had to be extremely economical, watch the consumption. I’ve had a mother and daughter or a father and son sharing a desk. An exam had to be sat at the end of the course. Our attitude was clear – ignorance is our arch nemesis, the sooner we vanquish it the sooner we will get out of poverty.73

Working in rural areas after the war remained the most demanding form of teacher engagement, just as it was before the war, and the new state continued the practice of assigning young female teachers to the country. The hardness of the teachers’ work was reflected by the fact that they were burdened with extracurricular activities and they had to perform several functions at the same time. In rural schools, teachers also managed and administrated their schools and had to submit performance reports on a regular basis. At the same time they were saddled with great teaching loads and had to work in crammed classrooms.

Pupils attended combined classes. In rural schools, teachers often had to work with over a hundred pupils at the same time.74 In addition, the material conditions of work and life in rural schools were exceedingly difficult. Village teachers were entitled to free lodging and heating fuel. 75

However, as most villages could not provide these entitlements, teachers either had no place to stay, or were given one to two rooms in the school itself, mostly in disrepair, without running water and sanitation. There are many eloquent testimonials from the day. When in 1951 teacher Krunoslava Lovrenović came to the village of Mošćanica near Zenica, she found the school in dire condition. This is how she describes it:

The school had two classrooms and a hall, and we also had a school kitchen. I don’t know if it even had bread at the time. There was a stove in the middle of the classroom. Both Muslim and Orthodox children went to my class together. When teacher Ljepša Džamonja and I first arrived, there weren’t even any locks on the doors. We taught so-called combined classes. First and third grade, or second and fourth, all together in one classroom in which instruction took place. First you teach one grade, then the other. As you work with the group you have to talk to, you assign the other group to draw something, to keep them still. The children were nice, well-behaved and tidy. Orthodox girls wore blouses with long black skirts and always plaited their hair, while Muslim girls wore Turkish trousers and blouses. Each wore whatever footwear they had – woollen socks, hide shoes or galoshes. There were shelves in the hall for coats. In winter, they would come to school wading through deep snow […]. Nobody provided firewood for the school, each child would bring a split log in the morning.76

Seeing that literacy courses in the country were organized in winter, teachers were often unable to exercise their right to holidays, and they worked hard during the school winter break. Yet, in spite of the exceedingly difficult material conditions of work, it seems that teachers, as a rule, carried out their tasks enthusiastically. This can be seen from the many testimonies and recorded interviews with teachers. Thus, for instance, in the Nova žena magazine, teacher Mileva Grubač from Višegrad went into raptures about working with women in her literacy course in the village of Dušća. She first relates how she was asked by the women from that village to “come and teach them, too” and promised to come on Sundays, as she was busy working at school or at the literacy courses in Višegrad. This is how she describes her first visit to the village, and the first class:

On Sunday, they sent a boy to fetch me lest I got lost and wandered about trying to find the village. I went up the Drina, thinking about that wonderful river, celebrated in song, bloodied. She flows quiet and blue, as though she remembers no evil. Steep hills tower above her banks, and on the patches of flatlands traces of aerial bombs can be seen. Here and there, the steel frame of a building juts out from the ground, loomed over by a factory chimney. These are the remnants of “Varda”, the erstwhile saw mill. I finally arrive in the village. I am welcomed by women with primers and writing tablets. Merry was our first class, when our grow-up pupils, with great patience and determination, began to write their first letters in unsteady strokes.77

With their enormous enthusiasm and engagement, progressive people’s teachers laid an important cornerstone for the building of a new state. Together with their colleagues, female teachers organized schools across the country and created new educational policies. In their struggle for new schools they not only changed the curricula, but also established completely new relations with their pupils. Rigid classroom hierarchy was abolished, and new learning and work practices were introduced, based on mutual trust and respect. The teachers were often full of parental concern for their pupils. Instead of corporal punishment they reasoned with pupils, nurtured a competitive spirit and camaraderie.78 This earned teachers a reputation, as well as the recognition and respect of the whole community, especially children and their parents. In addition, they organized cultural events in the areas where they served, and often worked at cultural institutions, from libraries and public reading rooms to amateur theaters and athletics societies.

One such exemplary teaching career is that of people’s teacher Nasiha Porobić.79 She was born in 1928 in Derventa. When the Partisans were in Derventa for a day in 1944, she joined the movement as a sixth-former. She was wholly unprepared when she joined the Partisans; at first she served as a nurse in Teslić, then she was elected to act as a delegate at a congress in Sarajevo, and after the war she went to the village of Korače, where she taught 146 pupils. First she completed a teacher training course in Banja Luka, and went on to study to be a teacher of Serbo-Croat. She worked during her studies. She organized all extracurricular activities at school, took part in all competitions for pupils and organized events. She stressed that she loved her calling and her pupils more than anything, and that she even neglected her family, two children and husband because of work. She received several awards and honors, including the Order of People’s Merit With a Silver Star.

I repeatedly listened to the recording of the interview with Nasiha Porobić, attempting to work out what it is in her voice and the way in which she answered the questions that has an unsettling effect, why her answers rouse a vague feeling of unease. No, her account is not a testimony of the futility of the struggle which, in her own words, gave her what she was able to receive. Her life was not without purpose, and there is no remorse. Nasiha claims that, if she could do it all again, she would not change anything, but this time she would join the struggle “with a bit more caution and better preparation. I’d take at least two changes of clothes. I wouldn’t just plunge headlong into it.”

What is unsettling is not the resignation in her voice, or her conciliatory tone – these are probably just the distance that comes with old age, or perhaps even a wisdom with which we assess our own decisions at the end of our lives. What is disturbing is the passive voice in the narration which suggests that Nasiha accomplished so much in her rich, fulfilling life, but had too little time actually to live this rich life. What is unsettling is the fact that she, like most women who participated in revolutionary struggle, uncritically agreed to support the myth of the woman who gladly gives up her life in favor of building the state and society of the future.80

However, that is one side of the coin. It is important to keep in mind that, in spite of the fact that great masses of women accepted the role of self-sacrificing heroines, modern-day Iphigenias, there existed systemic gaps, or conscious strategies of dealing with women, in this case people’s teachers, strategies that saw to it that the process of transformation from the oppressed to the progressive teacher remained unfinished.

3.2. Between the Emancipation and the Feminization of the Teaching Profession

If we are talking about the specificities of female socio-political organising in WWII, the massive scale of association, as well as the participation of large numbers of rural women and women of all social and ethnic backgrounds, are brought up as a rule.81. Ivana Pantelić argues that the mass mobilisation of women and their decision to join the Partisans was influenced by the mass arrival of female teachers to rural areas after 1918.82 In various ways, these teachers worked towards the emancipation and empowerment of women.

Although people’s teachers, along with nurses and female fighters, were distinguished activists of the anti-fascist movement and the NOB, they were not invited to participate in the executive bodies of the government and the highest bodies of the party during and after the war.83

On the contrary, the emancipatory figure of the teacher-fighter from the NOB gradually transformed into the figure of the great selfless mother who is supposed to raise a new generation through the process of compulsory primary education.

As noted by Amila Ždralović, the mass participation of women in combat units during the war also meant the beginning of struggle against the traditional notions of the woman’s role and place in society, in their families as well as in the units they were joining. From the stories about female partisans it may be concluded that in their units many of them were in charge of patriarchally defined female tasks, such as cooking and sewing. However, at the same time they do tasks patriarchally defined as male, and they often volunteer for the most difficult assignments. In this way they helped break traditional notions and stereotypes of the woman’s place and role in society.84

Thus was popularized the figure of the woman-mother, oppressed and kept in a state of ignorance by the patriarchal bourgeois order, who not only manages to bring herself to literacy in the revolutionary struggle by attending a literacy course, but also enters the educational process from the anonymity of the private sphere and teaches others. In Mi se borimo i učimo (We Fight and We Learn), a regular section in the AFŽ magazine Žena kroz borbu (Fighting Woman), one such transformation of a woman was described in an article about a celebration organized by the 16th Muslim Brigade in June 1944 at which distinguished fighters were decorated:

A mere year ago, Zumreta was hauling heavy ewers of water, scrubbing cobbles in courtyards, laboring in other people’s houses, far from books and any semblance of cultural life and work. Today she is being honoured as the best educator and cultural worker in her brigade […] Zumreta has acquired so much knowledge that she has been able to lead and teach others.85.

However, from the mid-1950s onward, it was precisely these attempts by women to ensure equality and new positions and social roles through selfless commitment, caring for others, volunteering and doing the hardest jobs that led to the loss of their hard-earn positions, after they had borne the brunt of the effort to rebuild the country which lay in ruins.86 In other words, they returned (more precisely: they were returned) to the confines of the traditional patriarchal roles. Thus, as Vjeran Katunarić puts it, the new socialist woman slipped from the heroic figure of the woman-fighter to the figure of the tame homemaker and ‘fashion-conscious’ woman:

Immediately after the war, [the figure of the woman-fighter] was supplanted by the woman from the socialist poster, the woman-builder in the factory, at the construction site, at sporting events, etc. That figure reflected the revolutionary zeal of the young people of both sexes, as well as the spontaneous assimilation of women into male activities. A strong flash of light gradually faded from culture and was overwhelmed by the evolution of standard patriarchal culture. Women were pushed into the private sphere, and as the living standard of the family rose, the patterns of petty bourgeois life were renewed […]. The tabloid press exploded in the 1960s as a consequence of the strengthening of the role of the market in the Yugoslav economy. The female press, focused on fashion and make-up, faithfully copies the Western model of the female body, the female inner life and sentimentality. Jacqueline Onasis and similar characters overshadowed the emancipating figures of female social-realist culture, female fighters, workers and athletes.87

In the post-revolutionary period, the figure of the progressive teacher follows the same path of transformation previously taken by all revolutionary female figures. Thus the people’s teacher, on the wings of the ideals of labor, first became a shock worker who, working more and more to meet the needs of her great metaphoric88 family, only to gradually put on (or be thrown into) the chains of patriarchy and tradition of the previous regimes. Her performing of the traditional and ‘natural’ female roles of the nanny of the nation, the caring mother of all pupils and their mostly illiterate parents, left the people’s teacher, like other working women in socialism, with less and less “time for self-management”. Not having time meant “being outside of time, outside of history, being left with your biological nature”89 permanently stuck in the state of becoming90. a progressive teacher.

However, it would be false to suggest that the struggle of the progressive teacher for full emancipation, independence, better material conditions of work and appropriate remuneration91 was left unfinished92 just because teachers obediently agreed to play the imposed roles and operate under unfavourable circumstances. We are dealing with a different, more complex phenomenon. Relying on Bloch’s claim about the women’s movement being obsolete or supplanted or delayed, and his hypothesis that after revolution it is the movement’s turn as a self-realisation of femininity, Nadežda Čačinović93 examines the quality of being delayed as a new element within the classical doctrine of the workers’ movement, and, among other things, she notes that the possibility of a different self-realization of femininity in post-revolutionary societies is still delayed, and that femininity reappears as an old greatness94

Čačinović explains that the very effort to include everyone in the work process, especially in the division of managing duties, is considered positive progress. In principle, it is acknowledged that ‘the New Woman’ is human and capable of superior achievements whilst performing all the traditional female roles (consoler, feeder, healer). However, she concludes, “the inner unsustainability of that role is acknowledged as ‘overburdening’, a euphemism which conceals the draining of women and a complete lack of improvement regarding the male role.”95

This process, from the emancipation to the feminization of the teaching profession, should first and foremost be seen from a wider ideological level of operation within which the hijacking and the abuse of traditional values in a new context takes place.96 Thus, even during the preparations for the mass agitation of women and the broad masses and their inclusion in the NOB, the leadership of the movement and its chief ideologues concluded that the existing tradition should not be openly questioned, because “respecting the tradition is a better/more expedient form of propaganda and a way to expand the movement.”97. As Lydia Sklevicky shows, neither the Central Committee of the Communist Party (CCCP) nor any other governing body of the NOP was trying to change traditional values; instead, the focus was on trying to modify them to suit the new historical moment. Therefore, “traditional ‘female values’ are not questioned or integrated into some new value system, but their emancipatory charge is reflected by their utility in spreading and strengthening the NOP.”98

In the case of the progressive teachers’ movement and the position of the progressive female teacher in the NOB, emancipatory values were insisted on only to the extent that this insistence was conducive to the successful achievement of the general goals of the struggle. This is why, Sklevicky explains, a pragmatic approach to traditional cultural values was developed, especially patriarchal ‘female’ values of reverence, selflessness, honour and honesty,99 the values which had become the cornerstone of all the social functions women had in the war. Thus it was believed that motherhood and its socialising role helps lay the groundwork for, among other things, brotherhood and unity100 Hence the figure of the progressive teacher was modeled on the figure of the caring mother who raises generations of pupils – children – in the new spirit of the times.

However, this trend continued during the post-war construction of a new socialist society. Although the authorities, in principle, made it possible for women to realize their political rights, the right to work, education and the protection of motherhood, and publicly promoted the idea of gender equality in all the spheres of activity, in the words of Renata Jambrešić-Kirin:

Yugoslav ideologues did not practise a radical break with the cultural forms of pre-revolutionary society based on the idea of gender differences and compatibility […] Yugoslav politicians eagerly resorted to the traditional repertoire of gender roles and symbols.101

The process of feminization102 of the teaching profession and the degradation of its social status (and, therefore the disempowering of women) began with the insistence on the figure of the teacher as a caring mother who sacrifices herself for the good of the community as a whole, and the claims that women manage to get things done and are better at teaching, which is ‘merely’ an extension of their ‘natural’ roles and a honing of their ‘innate capabilities’. As some feminist research103 has shown, gender stereotypes and gendered professional structures largely came about thanks to the rhetoric of a ‘proper/natural female profession’ which showed teachers as objects of knowledge, not active agents/subjects. Similarly, their professional activities and their work as educators were not seen as the practicing professional skills based on their education, which led to the gradual abandonment of progressive ideas about permanently honing pedagogical methods and improving classroom activities. Thus the concept of feminization of the teaching profession meant not only an increase in the number of female teachers, but also low status and inadequate remuneration, which necessarily led to the profession’s loss of social significance and a radical reduction of its power.

4. In Lieu of a Conclusion

The initial premise of this paper is that the figure of the progressive teacher reflects the limits of the professional emancipation of women as well as the consequences of the incompleteness of the process of construction and/or transformation of the woman as a new, independent, liberated and equal subject in a better, more humane society.

As the paper points out, in spite of the fact that women have made up the bulk of the teaching cadre since the end of WWII, research has so far paid little attention to the gender dimension of teaching. From 1918 to the beginning of WWII there was a rise in rural education and an increase in the number of young professional female teachers who joined the progressive teachers’ movement. Because female teachers were still in an exceptionally unfavorable financial position at the time and were subject to a law which discriminated against them by stipulating that they were to be paid less than men and by prohibiting marriage, except to other teachers, progressive female teachers fought for equal working conditions, equal rights and equal pay.

New socio-cultural revolutionary policies which were promoted and spread during the war led to radical changes in the status of female teachers. Many progressive female teachers, especially in the countryside and in the free territories in BiH, actively participated in these changes as well as in the implementation of educational reforms and the introduction of a new social order. Although the figure of the peoples’ progressive teacher was constructed as a distinguished female revolutionary figure by the new government and the new official ideology, after the war they were less and less politically active and intellectually committed to further empowerment and professional independence. Such development of the figure of the female teacher and the practice of female teaching is partly the result of the fact that the professional skills were treated as innate rather than acquired skills that required additional learning and honing. The teachers’ profession was increasingly feminized until the 1980s, when what was left of the teachers’ revolutionary efforts was a limited amount of cultural capital and a symbolic role.

Thus the transformation of the figure of the people’s progressive teacher could be ironically and succinctly represented in three images: from a teacher with a gun in one hand and a primer in the other, to a teacher with a red carnation tucked in her lapel, to a mid-eighties teacher who expected her pupils to give her a #16 lipstick on International Women’s Day.

Unfortunately, in the tumultuous post-war years of transition to a market economy, female teachers have lost even this symbolical importance and standing. In the tempestuous sea of educational reforms and the continued reorganization of primary education, the female teacher is no longer seen as a strong figure who shapes new generations and inculcates positive values in them. The teaching profession is further marginalized and devalued, and the rights and freedoms teachers enjoy in their work with pupils are limited and checked. Thus, it seems to me, one should advocate the establishment and empowering of a professional organization of female teachers which would find a way to act and formulate new progressive teaching policies, in spite of all the imposed divisions and segregation in the BiH education system.104 Feminism teaches us that for any kind of female professional association we need to find authentic figures from the past, predecessors we can rely on and build a more just, more responsible society. In that regard, this paper also pleads for research of the teaching profession and the status of female teachers conducted from a feminist and historical standpoint, research that would take a gender perspective and draw attention to the history of the development of this profession in BiH, in order to identify the structures which have continually oppressed female teachers and still keep them in an unfavorable position.

—Translated by Mirza Purić

References

| ↑1 | Letter by a girl named Vojka Beaković. This short letter by a war orphan who was transported from BiH to Slovenia for respite over the winter, testifies, amongst other things, to the ability of teachers to organize instruction successfully even in wartime, and to build rapport with their pupils. Here I quote it in its entirety: “Hello comrade teacher, first of all one should ask if you’ve started teaching year three. Me dear teacher, please let me know who has made it into year three, and who hasn’t. Have Milanka and Dana passed, they were doing quite well while I was there. I haven’t started over here yet, they say we’ll start this winter, and in summer I’m coming over again for you to teach me. Roses are red, violets are blue, me luvly teacher I believe in you. Dear teacher are you almost married yet? Because there is no time to waste, I beg of this letter to make haste. On a wooden bench I’m sat, in me right hand I’ve got a pen, in me left a kerchief white, I’m shedding tears as these words I write. Dear teacher reach out your hand to shake my own before the break of dawn, blossom ye roses, sprout tiny seed, do you teacher still remember me. I would give anything to be a bird on the wing and fly over to you. Long live comrades Tito and Stalin.” The letter was published in the section titled “Letters from the Children in Slovenia” in the magazine Nova žena 8 (1945), 12. The same issue features a detailed account of the departure of the first group of orphans for wintering in Slovenia. I thank Danijela Majstorović for bringing this letter to my attention |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This research was preceded by philosophical debates aiming to shed light on the position of women in socialism. Cf. Nadežda Čačinovič-Puhovski, „Ravnopravnost ili oslobođenje. Teze o teorijskoj relevantnosti suvremenog feminizma“, Žena 3 (1976): 125–128; Dunja Rihtman-Auguštin, „Moć žene u patrijarhalnoj i suvremenoj kulturi“, Žena 4–5 (1980); Blaženka Despot, „Žena i samoupravljanje“, Delo 4 (1981): 112–116; Nada Ler-Sofronić, „Subordinacija žene – sadašnjost i prošlost“, Marksistička misao 4 (1981): 73–80. In addition to these works, one of the first feminist-orientated studies, authored by the sociologist Vjeran Katunarić, should also be mentioned; it also points to the problem of reducing ‘the Woman Question’ to the status of a general social issue, which avoids ‘active opposition to those who maintain domination’. Cf. Vjeran Katunarić, Ženski eros i civilizacija smrti (Zagreb: Naprijed, 1984), 239. Also, a matter of exceptional importance is the international conference “Drugarica žena. Žensko pitanje-novi pristup?” organized in Belgrade in 1978, where the inequality of women in socialism in different social and political spheres was publicly discussed for the first time |

| ↑3 | Died in a traffic accident in 1990, aged 39 |

| ↑4 | Sklevicky, Lydia. “Karakteristike organiziranog djelovanja žena u Jugoslaviji u razdoblju do drugog svjetskog rata”, Polja 308 (1984); and “Žene i moć – povijesna geneza jednog interesa”, Polja 309 (1984). Here I reference the versions from the posthumous volume of Lydia Sklevicky’s works titled Konji, žene i ratovi. Zagreb: Ženska infoteka, 1996., edited by Dunja Rihtman Auguštin |

| ↑5 | Cf. Sklevicky, Konji, žene, op. cit. p. 15. |

| ↑6 | Cf. the edited book Žena i društvo. Kultiviranje dijaloga, Zagreb: Sociološko društvo, 1987, featuring papers by distinguished feminist theorists of the day: Rada Iveković, Žarana Papić, Blaženka Despot, Lydia Sklevicky, Andrea Feldman, Vesna Pusić, Željka Šporer, Gordana Cerjan-Letica, Vera Tadić, Vjeran Katunarića, Đurđa Milanović, Jelena Zuppa, Ingrid Šafranek, Slavenka Drakulić. |

| ↑7 | Senija Milišić made a pioneering contribution to Bosnian-Herzegovinian historiography of the day by researching the processes of emancipation of Muslim women in BiH. Cf. Senija Milišić „Emancipacija muslimanske žene u Bosni i Hercegovini nakon oslobođenja 1947 – 1952 (Poseban osvrt na skidanje zara i feredže)”. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Sarajevo, 1986. |

| ↑8 | According to Ines Prica, war yet again “postponed the tasks and the closing of planned gaps which certain periods leave behind in scholarly records or scholarly conscience, for times of peace.” Ines Prica, “ETNOLOGIJA POSTSOCIJALIZMA I PRIJE. ili: Dvanaest godina nakon „Etnologije socijalizma i poslije”, in: Lada Feldman Čale and Ines Prica, eds. Devijacije i promašaji. Etnografija domaćeg socijalizma, Zagreb: Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, 2006, p. 21. |

| ↑9 | See, among other things: Slapšak,Svetlana, Ženske ikone XX veka, Belgrade: Biblioteka XX vek – Čigoja Štampa, 2001.; Jambrešić Kirin, Renata. Dom i svijet. O ženskoj kulturi pamćenja, Zagreb: Centar za ženske studije, 2008.; Bosanac, Gordana. Visoko čelo: ogled o humanističkim perspektivama feminizma, Zagreb: Centar za ženske studije, 2010; Jambrešić Kirin, Renata and Senjković, Reana, Aspasia: International Yearbook of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European Women’s and Gender History, 4, 2010; 71–96; Pantelić, Ivana. Partizanke kao građanke, Beograd: Institut za savremenu istoriju – Evoluta, 2011. ; Jambrešić Kirin, Renata. „Žena u formativnom socijalizmu“, in: Refleksije vremena 1945-1955 Zagreb: Galerija Klovićevi dvori, 2013. |

| ↑10 | Cf. Batinić, Jelena. “Proud to have trod in men’s footsteps: Mobilizing Peasant Women into the Yugoslav Partisan Army in World War II”, (MA thesis, Ohio State University, 2001), and idem, “Gender, Revolution, War: The Mobilization of Women in the Yugoslav Partisan movement in World War II” (PhD thesis, Stanford University 2009); Stojaković, Gordana. Rodna perspektiva u novinama Antifašističkog fronta žena u periodu 1945-1953, (PhD thesis, University of Novi Sad, 2011), Bonfiglioli, Chiara. Revolutionary Networks. Women’s Political and Social Activism in Cold War Italy and Yugoslavia (1945-1957) (PhD thesis, Utrecht University, 2012), and Jelušić, Iva. Founding Narratives on the Participation of Women in the People’NOB in Yugoslavia (MA thesis, Central European University, 2015). Some of these research papers were based on the first studies of the participation of women in the NOB conducted at American universities. Cf. Reed, Mary Elizabeth. Croatian women in the Yugoslav Partisan resistance, 1941–1945 (PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1980.) and Webster, Barbara Jancar. Women & Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945, Denver: Arden Press, 1990. Most of these works were subsequently published as monographs. |

| ↑11 | Studies about women in the post-war period are more often sponsored by NGOs and civic associations then by official institutions or history departments. Cases in point would be the books by Tanja Lazić, Ljubinka Vukašinović and Radmila Žigić, Žene u istoriji Semberije Bijeljina: Organizacija žena Lara, 2012, and by Aida Spahić et al., Zabilježene – Žene i javni život Bosne i Hercegovine u 20. vijeku, Sarajevo: Sarajevski otvoreni centar, Fondacija CURE, 2014. For instance, only one BA thesis of that kind was defended at the Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo: Emira Muhić, Žena u socijalizmu u Bosni i Hercegovini od 1945. do 1971. godine prema časopisu ‘Nova žena.’ ‚BA thesis, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Sarajevo, 2012. |

| ↑12 | The archive was created in the course of the activities of the association for culture and the arts “Crvena”, Sarajevo. More about the archive and the project at http://www.afzarhiv.org/o-nama |

| ↑13 | For more details on the state of archivalia on WWII, the incompleteness of the fonds and the collections, see: Kujović, Mina. “Stanje arhivske građe o Drugom svjetskom ratu u Bosni i Hercegovini” in: Šezdeset godina od završetka Drugog svjetskog rata: kako se sjećati 1945. godine. Proceedings, Sarajevo: Institut za istoriju, 2006, pp. 217–235. |

| ↑14 | As early as 1953, the first systematic triennial gathering of archivalia or records on women’s wartime was started. For more on the launching of this archive and its scope in its initial phase see: Jambrešić Kirin, Renata. Dom i svijet, pp. 31–33. |

| ↑15 | With due awareness of the numerous difficulties in creating female history through archivalia, press clippings, recorded accounts and oral sources. For more on certain challenges facing research see: Bonfiglioli, Chiara. “Povratak u Beograd 1978. godine: Istraživanje feminističkog sjećanja” in: Glasom do feminističkih promjena, eds. R. J. Kirin and S. Prlenda, Zagreb: Centar za ženske studije, 2009, pp. 120–131 |

| ↑16 | Milić, Anđelka. “Patrijarhalni poredak, revolucija i saznanje o položaju žene, Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima 19. i 20. veka”, Položaj žene kao merilo modernizacije: naučni skup, Belgrade: Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije, 1998. Quoted in: Petrović, Jelena. “Društveno-političke paradigme prvog talasa jugoslavenskih feminizama,” ProFemina special issue (2011): 59–81, 62–3. The author explains that the purpose of female history is not to fill the gaps in the existing historiographical canon, but to transmit the knowledge based on the female historical experience and everything that had been systematically left out. This approach makes it possible finally to break “the endless circle of discovering and forgetting female history, emancipation and resubjugation, from the infinite renewal of the patriarchal order of values and relations which returns with a vengeance with every new historical episode.” Ibid. |

| ↑17 | Milić, in: Petrović, “Socio-Political Paradigms”, op. cit. 63. |

| ↑18 | Including: Pejanović, Đorđe, Historija srednjih i stručnih škola u BiH, Sarajevo, 1953.; Esad Peco, Osnovno školstvo u Hercegovini od 1878. do 1918., Sarajevo 1971; Mitar Papić, Školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini za vrijeme austrougarske okupacije (1878-1918), Sarajevo, 1972, Istorija srpskih škola u Bosni i Hercegovini do 1918. godine, Sarajevo 1978.; Hrvatsko školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini do 1918. godine, Sarajevo 1982., Školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini (1918 – 1941), Sarajevo, 1984., Hajrudin Ćurić, Muslimansko školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini do 1918. Godine (Muslim Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina until 1918), Sarajevo, 1983, and Azem Kožar, “Osnovno školstvo u toku Drugog svjetskog rata (1941-1945)” and : Osnovno školstvo u Tuzli (istorijski pregled) Tuzla, 1988. |

| ↑19 | In addition to the works which appeared in publications such as “Zbornik sjećanja treće poslijeratne generacije učiteljske škole u Derventi juni 1951. godine” or “Zbornik radova 100 godina učiteljstva u Bosni i Hercegovini” and the papers presented at a symposium organized in Sarajevo in 1987 to mark the centennial of the first school of education in the country, the role of the teacher was examined in more detail by Mitar Papić in his books Školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini od 1941. do 1955. godine, Sarajevo, 1981, and Učitelji u kulturnoj i političkoj istoriji BiH, Sarajevo (Svjetlost, 1987) and, to an extent, by Mato Zaninović in his study titled Kulturno-prosvjetni rad u NOB-u (1941 – 1945), Sarajevo, 1968, and Snježana Šušnjara, “Učiteljstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini za vrijeme Austro-Ugarske”, Anali za povijest odgoja 12 (2013): 55–74. An MA thesis was defended at the Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo in 2014, titled „Uloga učitelja u prosvjetnim, političkim i kulturnim promjenama u BiH od 1945. do 1951. godine.” The author Ademir Jerković examines the material conditions of teaching during and after the war and looks at teachers’ contribution to the general cultural and educational progress in BiH; a BA thesis on the position of teachers during the Austro-Hungarian occupation was also defended. See: Anđa Bandić, Društveni položaj učitelja u Bosni i Hercegovini za vrijeme Austro-Ugarske, BA thesis, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Sarajevo, 2011. |

| ↑20 | Papić, Mitar. Učitelji u kulturnoj i političkoj istoriji Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1987, p. 3. |

| ↑21 | Quoted in: Suzana Jagić, “Jer kad žene budu žene prave: Uloga i položaj žena u obrazovnoj politici Banske Hrvatske na prijelazu u XX. stoljeće”, Povijest u nastavi 11 (2008): 77–100, 83–4. |

| ↑22 | The author justifies this bias by citing the fact that progressive female teachers in the interwar period did not form separate professional associations. Cf. Jovanka Kecman, Žene Jugoslavije u radničkom pokretu i ženskim organizacijama 1918-1941, Belgrade, 1978, p. 373. |

| ↑23 | Cf. Kujović, Mina. Muslimanska osnovna i viša djevojačka škola sa produženim tečajem (1894-1925) – prilog historiji muslimanskog školstva u Bosni i Hercegovini,” Novi Muallim 41 (2010): 72–79; and idem, “Hasnija Berberović – zaboravljena učiteljica – prilog historiji muslimanskog školstva u Bosni i Hercegovini”, Novi Muallim 40 (2009): 114–118; Šušnjara, Snježana. “Jagoda Truhelka”, Hrvatski narodni godišnjak 53 (2006): 239–256.; idem, “Jelica Belović Bernadrikowska”, Hrvatski narodni godišnjak 54 (2006): 66–76., idem, “Školovanje ženske djece u BiH u vrijeme osmanske okupacije 1463.-1878, Školski vjesnik 4. (2011); and idem, “Školovanje ženske djece u Bosni i Hercegovini u doba Austro-Ugarske (1878.-1918.), Napredak 155 (4) (2014): 453–466. In her comprehensive study on the position of women in society in 19th- and 20th-century Serbia, Neda Božinović also offers a general overview of the social status of teachers in the lands which made up the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, as well as a short overview of the circumstances in BiH during the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian rule. Cf. Neda Božinović, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji: u XIX i XX veku, (Belgrade: “Devedesetčetvrta” and “Žene u crnom”, 1996). It should be pointed out that most of these works do not engage critically with the traditional historiography and move towards filling the gaps in the existing historical models (markedly ethno-national in character after the last war). The focus is on the effort to fit distinguished female figures into the existing canon, and there is almost no discussion of how and why one of the most popular female professions remained historically unrepresented, and no discussion of the still-pressing issues of educational systems and education of girls and women. More on the concept of gender as a “societal organization of sexual difference” in historical research in: Joan W. Scott, Rod i politika povijesti (Gender and the Politics of History), Zagreb: Ženska infoteka, 1988, 2003, and Feminism and History, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996. |

| ↑24 | Jambrešić-Kirin, Renata. “Politike sjećanja na Drugi svjetski rat u doba medijske reprodukcije socijalističke kulture”, Lada Feldman Čale and Ines Prica eds., Devijacije i promašaji. Etnografija domaćeg socijalizma, Zagreb: Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, 2006. p. 157. |

| ↑25 | Cf. Katz, Vera. “O društvenom položaju žene u Bosni i Hercegovini 1942.-1953.”, Prilozi 40 (2011): 135–155 |

| ↑26 | In her speech at the Second Session of ZAVNOBiH, Danica Perović pointed out that the new figure of the woman was “was a female combatant who has grown and matured politically during the struggle, emancipated herself and is able to lead and make decisions on every issue pertaining to the struggle and the life of the people.” Cf. Govor Danice Perović na Drugom zasjedanju ZAVNOBiH-a u Dokumenti 1943–1944, Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša, 1968, p. 200 |

| ↑27 | These changes affected all of Yugoslavia, yet several papers point out the substantial differences between the previous economic and socio-cultural circumstances in different parts of this former state. The countries which comprised the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and subsequently the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, had somewhat different social orders, and substantially different demographic make-ups. This necessarily meant substantial differences and specificities regarding the position of women in these countries – from marital status and access to education to the right to act in the public sphere. Examining this question in a separate Bosnian-Herzegovinian context seems justified precisely because of those differences and specificities. |

| ↑28 | During the Ottoman rule in BiH, education was private and religious only. After the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austro-Hungarian authorities opened more and more state schools, the so-called “People’s Primaries”, which operated alongside the existing private religious schools, and their curricula, textbooks and reading lists were mandated by the state. At the beginning of the Austro-Hungarian occupation of BiH, 535 so-called sybian-mekteb schools were active in the country (this is to be taken with a grain of salt; a paper by Snježana Šušnjara claims that in 1876 there were 917 mektebs), 54 Catholic schools and 56 Serb Orthodox schools; towards the end of the Austro-Hungarian rule in BiH, in the school year 1912/13, there were 331 state schools in addition to the religious schools. Taken from: Mitar Papić, Školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini za vrijeme austrougarske okupacije 1878-1918, Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša. 1972. |

| ↑29 | The first girls’ school in the Ottoman period was opened in Sarajevo, as late as the school year 1857/58, thanks to the tenacity, selflessness and dedication of the teacher Staka Skenderova, the first woman in Bosnia and Herzegovina to write a book (Ljetopis Bosne 1825—1856.). The second girls’ primary was established in 1866 by the Protestant suffragette Miss Adelina Paulina Irby. Both schools were boarding schools, and both were attended by girls of all faiths. Seeing that some of the pupils became teachers after graduation, we may treat these schools as the first girls’ schools of education in BiH. Five years after Miss Irby opened her school, nuns from Zagreb opened the first Catholic girls’ school in Sarajevo. The Sisters of Charity of St Vincent De Paul soon opened schools in Mostar (1872), Dolac near Travnik (1872), Banja Luka and Livno (1874). Muslim girls, as a rule, attended religious schools (mektebs). The data on the schools comes from the studies by Mitar Papić, Istorija srpskih škola u BiH (A History of Serb Schools in BiH), Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša, 1978; and Snježana Šušnjara “Školovanje ženske djece u Bosni i Hercegovini u doba Austro-Ugarske”, op. cit. |

| ↑30 | As Dinko Župan relates, pedagogical discourse in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy supported sex policies by producing knowledge on different traits exhibited by sexes on which gender roles were based. It was precisely in the secondary schools that the desirable female identities were shaped. Župan writes: “The main traits the female students were to develop at the secondary school for girls were piousness, sincerity, chastity, meekness, shyness, modesty and taciturnity.” A female identity developed along these lines was represented as natural and immutable. But this identity was only seemingly universal, because the female identity was criss-crossed by a web of other identities (class, religious, ethnic). Thus, for instance, every class had a unique way of implementing the universal determinants of womanhood. The desirable behaviour of a mother, wife and a home-maker varied across classes. Cf. Župan, Dinko. “Viša djevojačka škola u Osijeku (1882-1900)”, Scrinia slavonica 5 (2005), 366–383. |

| ↑31 | Cf. Jagić, “Jer kad žene”, p. 80. The author points out that women were educated with the sole purpose of becoming good wives and mothers, because only an educated mother and wife was able to “lay the religious and moral groundwork for the kind of upbringing on which the well-being of the homeland would depend.” Ibid. |

| ↑32 | Given that patriarchy can be thought in various ways today, and that it is not a self-explanatory system, I am taking my cue from Dunja Rihtman-Auguštin, who lists “the domination of men in the workplace, decision-making and property relations […] as well as the separation of women from the public sphere and their subordination” as the basic features of patriarchy. Rihtman-Auguštin, Dunja. Etnologija naše svakodnevice. Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1988. p. 193 |

| ↑33 | Cf. Božinović, Neda. Žensko pitanje, op. cit. p. 80 |

| ↑34 | Cf. Kujović, “Hasnija Berberović – zaboravljena”, p. 116. |

| ↑35 | While other civil servants had salaries ranging from 2,900 to 7,500 dinars, teachers were paid 705 to 2,500 dinars. Reč istine br. 1 (1940), 6. Quoted in: Rade Vuković, Napredni učiteljski pokret između dva rata, Beograd: Pedagoški muzej, 1968, p. 109. |

| ↑36 | The resolutions regularly demanded matching remuneration to the prices of essential items, matching the salaries of married female teachers to those of male teachers (“equal pay for equal work”), abolishing the III price grade, the rejection of group V just as with other civil servants, etc. Cf. Vuković, Napredni učiteljski, p. 93. |

| ↑37 | Progressive schooling is understood as schooling based on socialist ideas. As early as 1873, Serbian teachers in Zemun launched the socialist teachers’ Učitelj which gathered progressive teachers from the Vojvodina region; in Serbia proper, a social democratic teachers’ club was established in 1907 and it stood for free compulsory universal education at all schools, i.e. for the idea that the state should build and maintain people’s schools. Cf. Vuković, Napredni učiteljski, 10. As early as 1908, the pedagogic book series Budućnost served as a platform for progressive pedagogy and had an increasingly strong influence on the teaching profession. However, whereas a certain percentage of the teaching cadre in Serbia and Croatia belonged to various social-democratic organizations, teachers from BiH, as a rule, did not enter political life openly during the Austro-Hungarian rule, and were therefore less in touch with revolutionary pedagogic ideas. It was only after 1920, and the Congress of Teachers of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes that the number of progressive teachers in BiH rose. Mitar Trifunović Učo especially distinguished himself as one of the first active members of the workers’ movement and a Communist Party of Yugoslavia MP. Cf. Papić, Učitelji, pp. 45, 46. |

| ↑38 | After the Protection of Security and Social Order Act was passed and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia banned (by a decree known as “Obznana”) in 1921, the party went underground. The decree also banned the Communist Teachers’ Club, as well as the party and union press. The 6 January Dictatorship abolished permanent employment for teachers and put them under police surveillance, while it continued to persecute, fire and imprison them. More in: Vuković, Napredni učiteljski, 14, 15 |

| ↑39 | In: Kecman, Žene Jugoslavije, op. cit. pp. 381, 82 |

| ↑40 | Quoted in: Radisav S. Nedović, Čačanski kraj u NOB 1941-1945: žene borci i saradnici, Čačak: Okružni odbor SUBNOR-a, 2010., pp. 59–63. |

| ↑41 | In: Kecman, Žene Jugoslavije, op. cit. 373. |

| ↑42 | Ibid. p. 375. |

| ↑43 | At this congress, i.e. at the Nineteenth Annual Supreme Session, the representatives of political groups submitted three candidate lists for the executive, steering and other committees and organs of the Yugoslav Teachers’ Association. Three political groups were active within this umbrella organisation – the Yugoslav Radical Union (YRU) or the New Teachers’ Movement, a group built round the so-called class line of bourgeois democrats, and a group gathered round the Učiteljska straža journal including the teachers’ co-operative “Vuk Karadžić”, which gathered communists and other progressive teachers, male and female. At the congress, the communists submitted a list which represented the interests of the third group of teachers. Seeing that it was third in succession, this group was subsequently called Treća učiteljska grupa (Teachers’ Group Three). More in: Rade Vuković, Napredni učitelji, pp. 74–88. The congress was notable for gathering female teachers from all over the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in a separate meeting, to discuss the legal and financial status of female teachers. On that occasion the female teachers motioned again to create female departments within regional teachers’ association. Cf. Kecman, Žene Jugoslavije, n.dj., p. 381. |

| ↑44 | Cf. Kecman, Žene Jugoslavije, op.cit. p. 375. |

| ↑45 | Ibid. p. 374. |

| ↑46 | An article titled “Vrijeme zrenja” published in a volume of testimonies about the engagement of women of Mostar in the pre-war period describes various activities of women which took place at the library and reading room. More in: Mahmud Konjhodžić, Mostarke, fragmenti o revolucionarnoj djelatnosti i patriotskoj opredjeljenosti žena Mostara, o njihovoj borbi za slobodu i socijalizam, Mostar: Opštinski odbor SUBNOR-a, 1981., pp. 36–38. |

| ↑47 | Cf. Papić, Učitelji u kulturnoj, 67. Teacher recipients of the 1941 Commemorative Medal are: Vera Babić, Mila Bajalica, Jela Bićanić, Milka Čaldarović, Dušanka Ilić, Milica Krpić, Danica Pavić, Jela Perović, Lepa Perović, Nada Prica, Mica Vrhovac and Zaga Umićević. Ibid, p. 82. |

| ↑48 | Gladanac, Sanja. “Uspostava državnog školstva na području Velike župe Vrhbosna”, Husnija Kamberović ed., Bosna i Hercegovina 1941: Novi pogledi. Zbornik radova. Sarajevo: Institut za istoriju u Sarajevu, 2012: 67–97, 74, 75. |

| ↑49 | Cf. Kožar, Azem. “O nekim aspektima obrazovno-odgojne politike Narodnooslobodilačkog pokreta na području Bosne i Hercegovine 1941-1945”, Šezdeset godina od završetka Drugog svjetskog rata: kako se sjećati 1945. godine. Zbornik radova, Sarajevo: Institut za istoriju, 2006, pp. 235–248, 236 and 237. |

| ↑50 | Zaninović, Kulturno posvjetni rad, p. 20. |

| ↑51 | Zaninović, op. cit. p. 21. |

| ↑52 | This textbook had only 44 pages and was a cross between a primer and an exercise book. It is notable because, among other things, it represents an historical document which features, for the first time, content promoting different educational, pedagogic and ideological values. Cf. Mihailo Ogrizović (1962). Quoted in Papić, Učitelji u kulturnoj, p. 74. |

| ↑53 | In: Kožar, “O nekim aspektima”, op. cit. |

| ↑54 | Kožar, “O nekim aspektima”, op. cit. |

| ↑55 | The first national conference of the AFŽ Yugoslavia was held from 6–8 December 1942 in Bosanski Petrovac. The tasks defined during the conference preparations were agreed upon, and two basic sets of tasks which the AFŽ was to carry out during the war were confirmed: assisting the armed forces and ensuring the normalization of life in the liberated territories, and achieving political and cultural emancipation of women and their integration as equals into the NOB and the fight for a new society. Cf. Sklevicky, Konji, žene, op. cit. pp. 25–26. |

| ↑56 | In: Papić, Učitelji u, pp. 78, 79. |

| ↑57 | Zaninović, Kulturno posvjetni rad, 158, 159 |

| ↑58 | In: Papić, Mitar. Školstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini 1941-1945, pp. 4–11. |

| ↑59 | Zaninović, op. cit. p. 176. |

| ↑60 | Ibid. pp. 187, 190 |

| ↑61 | For more on these courses see: Zaninović, Kulturno prosvjetni, n. dj., pp. 124, 180–184. |

| ↑62 | Zaninović, op. cit, p. 185. |

| ↑63 | A good example is the career of Rada Miljković, who started out as a progressive teacher, became a successful agitator and finally a soldier killed in action in 1942 near Bugojno; in 1953 she was posthumously awarded the Order of the People’s Hero of Yugoslavia. A detailed account of her revolutionary path is available here: http://www.savezboraca.autentik.net/licnosti_rada_ miljkovic.php |