Written after the Vitry-sur-Seine and Montigny-lès-Cormeilles “affairs,” and published in Le Nouvel Observateur, no. 852 (March 9, 1981), this article earned my expulsion from the French Communist Party (PCF) at the time (of which I had been a member since 1961), via a resolution of the Paris Federal Committee passed the same day and which appeared in L’Humanité on March 10, 1981. It also prompted two clarifications I must note: one is from Henri Alleg, concerning the circumstances surrounding the publication of La Question in 1958 (see L ’Humanité, March 18, 1981), and the other is from Mme. Béatrice Maillot concerning her brother’s engagement on the side of the FLN, and the relationships between the Communist Party of Algeria and the PCF (see Le Nouvel Observateur, no. 853, March 16, 1981). The article was republished in Les frontières de la démocratie (Paris: Editions La Découverte, 1992).

Racist, the party of Moussa Konaté 1 and Henri Alleg, the party of those who died at Charonne, to whom Communist deputies have asked that we finally erect a commemorative monument? Antiracist, the party of Guy Poussy 2 and Paul Mercieca, 3 the organizers of the bulldozer operation at Vitry, the party of Robert Hue, 4 who used an Algerian family to pit a small city against another family of Moroccan workers? No communist today can avoid this question.

I was not in the streets, near the Charonne metro station, on February 8, 1962. A month and a half prior, on December 19, during the first of the truly massive united demonstrations against the OAS, against the attacks by de Gaulle and Debré, and for immediate peace in Algeria, the Brigades spéciales of [Maurice] Papon’s prefecture, armed with their “widgets,” from those rifles to the iron crosses they used as clubs, sent me to the ground along with dozens other members of the Communist Youth’s service d’ordre. There were no deaths (yet) that day. Among the wounded, some managed to be carried to the hospital by comrades, by anonymous friends who emerged from the great fraternal crowd. Others, “rounded up” by the police, were transported first to Beaujon Hospital, where they were specially “looked after.” The same was the case on February 8, and several times since. I can still recall, in the moment the cops charged, that calm assurance of a group of workers in the CGT’s [the General Confederation of Labor] service d’ordre, spreading throughout our disoriented ranks to lead us, knowing by instinct and experience that there would be fewer and less serious injuries in a resistant crowd than in a fearful crowd seeking to flee. And I remember that remark from an intern at Saint Antoine hospital, upon seeing me arrive with blood on my head: “Serves him right. What was he going to do about it?”

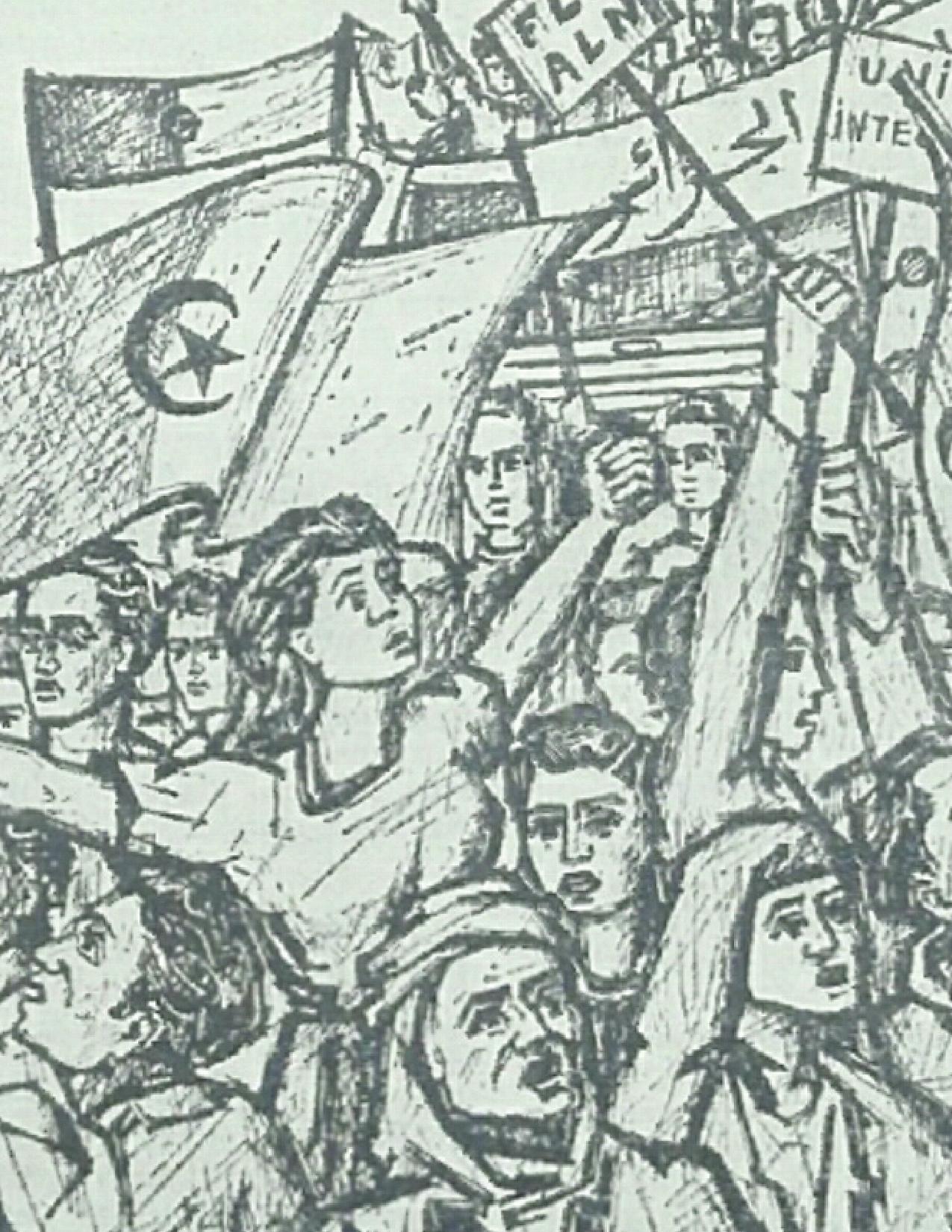

What were we going to do? We knew better than him, poor parrot of his class discourse, isolated from his generation, in a historical period when all the youth, workers, and even the bourgeoisie, felt it necessary to take a side against racism, imperialism, and war. Several weeks later, workers, employers, students, teachers, numbering anywhere from 800,000 to a million, took to the streets to bury the eight people who died at Charonne – seven of whom were communists – and block the streets. Who could pretend that those eight people, and the million who came out, did not have an impact on those in power when they made the decision to abandon their double game and recognize the Algerian FLN’s demand to govern its own country?

I am not recalling these experiences to summon the romanticism of youthful memories, but to provide some reference points for thought. I think that these reference points are necessary today, when for men and women of this country and elsewhere, the French Communist Party (PCF) might rather conjure the image of a bulldozer dumping heaps of soil in front of a house in the banlieues, where a hundred or so Malian workers, unwelcome everywhere, had settled.

To the question on everyone’s minds and lips – “How did the Party come to this?” – I challenge the notion that one can provide a simple, black and white answer. For some, it is the eternal “red fascism” that had finally revealed its naked truth. For other, first of all those in its own ranks, it was unexpected, the stupefaction of a brutal reversal to what they had always believed: the Party had “fundamentally changed…” Not to mention those who only saw it as one episode, a more or less explicable result of pre-election one-upmanship in these difficult times we are going through. But if we wish to understand this event, if we want to act while there is still time, it is not enough to resort to a formula. And we must not only talk about the present moment, not only about immigrants and red suburbs, or youth and drugs – but also about the Party’s anticolonialism and the form it has taken in the recent past, now repressed and covered over by myths.

The French Communist Party has always referenced – today more than ever – the deaths at the Charonne metro, as well as to the martyrdom of Audin and Alleg, or the sacrifices of Iveton and Maillot, to bear witness to its anticolonial engagement. I would like to discuss here why this reference, which many of my generation had good reasons for committing themselves to, has always been a deep source of embarrassment for me. I see in it a long-term equivocation, which we are paying the consequences for in the present.

To begin with, over the past few years, this legacy has been invoked to emphasize the contrast between the PCF and the task of the Socialist Party and its leaders. The historical facts are there, in fact. It was indeed Mitterrand who, as Interior Minister in 1954, said: “Algeria is France. The only possible negotiation is war.” And it was the socialist government (invested with “special powers,” also voted for by Communist deputies) that started the “dirty war,” which was continued by de Gaulle after the 1958 Algiers putsch. But first of all, what is this Manichean vision of history that seeks the sin of some to be an indefinite witness for the grace and virtue of others? Why, moreover, is our correct policy then a guarantee now? And above all: how can the detestable policies of the socialists erase and render moot any analysis of our own uncertainties?

There is no question that in the years between 1958 and 1962, no opposition to the colonial war could have triggered a historically effective mass mobilization without the CGT, without the Communist Party. We who entered the Party were perfectly aware of this, as we knew that the role of organization and assembly was not a matter of chance. And Marxist theory, even if frozen in a few formulae, along with organic implantation in the working class were decisive factors. Our analysis at the time remains correct: the facts have confirmed it. But for all that, we did not forge an ideal image of this organization. Perhaps, having had the opportunity to come into the Party later in its history, after the trials of the Popular Front, Liberation, the Cold War, and the first tests of “actually existing socialism,” we could make this choice without representing the Party and its leaders as infallible. We saw the limits and contradictions of its anticolonialism, particularly concerning Algeria (which Thorez had previously called a “nation in formation,” thereby contesting that it was ready for independence and ready to join the Arab world – and this error did not end up harming him). But we chose the principal aspect, confident that the class struggle and people’s struggle would irresistibly move in that direction…

But let’s return again to Charonne. I find it very revealing of the Party’s attitude which, both today and yesterday, glorifies the fallen comrades but never recalls why the demonstration was held in the first place. One hears only of an abstract and mythic anticolonial struggle. Many of us can bear witness with lucid memories: if there was a February 8, 1962 and before it a December 19, 1961, these united demonstrations in which everyone’s divisions and sectarianisms were put aside, it is only because the terrible event of October 17, 1961 happened, of which the Party never speaks, nor anyone else for that matter.

On that day, in fact, thousands of Algerians – men, women, and even children – unarmed and ignoring the imposed curfew, left the bidonvilles of Nanterre and Aubervilliers. Following the workday, instead of returning to hole up in their ghettos – and those were really ghettos! – they answered the FLN’s call and “descended” into Paris to proclaim their desire for liberation. The Brigades spéciales awaited them. The next day, the bodies were recovered by the hundreds (the exact number has never been given) from the Seine, from Saint Cloud to Mantes… Yes, in the end it is essential to remember that without the sacrifice of those Algerian workers, tragically isolated, without the shock it generated in public opinion, the French working class and its organization would never have been shaken up. What, then, is the Party leadership waiting for, to finally put the immigrant Algerian workers of October 17 and the French workers of February 8 together in the same memorial? Why is it waiting to ask one of its municipalities in a working class suburb, which trusts the party and “houses” [hébergent] so many brothers and sons who have set an example for us, to erect a monument to the victims of October 17, 1961?

After having long thought about what these historical facts mean, I am now convinced that they clarify, in a decisive fashion, whole swathes of our national history and the role the Communist Party has played in them. Two aspects should not obscure one another: neither the fact that, ultimately, the liberation struggle and the national class struggle converged against their common adversary, nor the fact that this convergence intervened so late and in so incomplete a manner. For the Algerians went to the frontlines on their own, and we went into the streets in turn; surprising as it may seem, they were not linked to the organization of the demonstration! The latter was primarily a demonstration against fascism and for peace, to end a war that most French people no longer wanted to fight, but only secondarily for independence, because the former was the condition of the latter. A fortiori, the protest was not fully about class internationalism, although it was present and active. This why it was indeed representative of the limits and contradictions I mentioned above.

Faced with an apologetic history, I do not intend to initiate a retrospective trial. Objective explanations and knowledges are needed in order to clarify the present. Where do the hesitations of the PCF’s anticolonialism stem from, which is still mobilized, with all the risks, in connection to the situations in the Rif and Indochina? Certainly, against the myths of a spontaneous “class consciousness,” the persistent effects of belonging to an imperialist nation should be considered, whose colonial (and neo-colonial) benefits leave some “crumbs” for the workers and, consequently, their organizations. Certainly, the Party’s grounding in Algeria itself should be considered too, in a European population that could even less escape the illusions and alibis of the French “civilizing mission”… Above all, the nationalism of the PCF should be considered, that surprising concentration of contradictions in which the legacy of the working class’s patriotic role in the anti-fascist resistance and the worst “great power” (or medium power) chauvinisms, cemented by the influence and mimicking of Soviet nationalism, are mixed together.

It is clear enough, in fact, that today there is no incompatibility (much to the contrary) between this kind of nationalism and the degraded form in which we were led, in a context of pitiless confrontations, to the “unconditionally defense” of the Soviet state, from whom the revolutionaries the world over expected indispensable support, if not greetings. Both fed into, and concealed, the other. But the Algerians fought under a different ideology than ours (which set them apart from the Vietnamese). Their Mecca was not that of communism. To discover paths of common action with them, beyond the objective difficulties, the Party had to overcome both its internal nationalism and relativize its view of the “camps” comprising the world. That was a lot to deal with, apparently.

We now know that those leaders of ours (like Waldeck Rochet or Laurent Casanova) who sought to wrench the party away from its wait-and-see attitude to play a more decisive role in supporting the national liberation struggle of the Algerian people led by the FLN were also, in part, those who correctly saw the meaning of Gaullism, and were also – following others – accused by Thorez and Duclos of “bourgeois nationalism.” The fact is that after having voted for special powers to be given to Guy Mollet (perhaps awaiting a miraculous solution to the problem: this is one of the famous “errors of ’56,” recently noted in sibylline formulae), after having stopped – in order to not be cut off from the masses,” the protest movement among conscripts [le mouvement des appelés], in which young communists played an active role, it took the Party leadership years to come to a clear position. For fear of running too far ahead, the Party found itself regularly running late. But this was not the Party that publish Henri Alleg’s The Question. This was not the Party that created the Audin Committee, but a group of left-wing Christians, Trotskyists, and several “dissident” socialist and communist militants avant la lettre. It was the UNEF, directed by the same “rightist” and “leftist” militants, that was the first trade union to meet with an Algerian syndicalist organization. It was the worker-militants of the French Confederation of Christian Workers (the same ones who went on to form the French Confederation of Democratic Workers) who so often showed the way for the CGT.

From the day that the working masses, following-preceding the Party, entered the struggle, the squabbles over priority became derisory. That is always the case in retrospect. But the fact remains that the PCF has no right to claim a monopoly on anticolonialism. And above all, in this explicable, if not justifiable, hesitations, a perhaps fragile yet real historical opportunity was lost, whose consequences would have changed many things.

The opportunity was missed to forge an organic unity in struggle between French workers and immigrant workers. For both, internationalism remained, save for some exceptions, a calculus of convergent interests, not a common practice in which one learns little by little to know each other, to overcome contradictions, to envisage a shared future.

Who can say today how such unity would have changed the history of independent Algeria, for its benefits and for ours? In France, there were – and still are – more than a half million Algerian proletarians in daily contact with the world of large-scale industry and the traditions inherited from October 1917 and 1936. They provided a good number of militants and cadres to the patriotic struggle. Their influence could have been crucial in building Algerian socialism – and thus ultimately in the struggle for a “new international order,” different from the one prepared for us by multinational capitalism, in the face of technocratic military interests and a “national bourgeoisie” quick to turn the heroism of its people to its own exclusive benefit…as with all bourgeoisies! Today, Algeria is certainly a country whose role in the world is more progressive than others. It’s also a country where workers are deprived of any possibility for trade union or autonomous political organization, and therefore of any immediate revolutionary possibility.

Who can say how this unity would have changed the history of class struggles in France itself, at the moment when the major shift in the proletariat took place, as those “O.S. strikes” came to the fore, with the mobilization of immigrant workers as a primary factor? Emerging from the Algerian War as the party of the whole working class, would not the PCF have appeared to Portuguese, Antillean, African, or Turkish workers as their “natural” organization? And would the party not have had, then, from ’68 through the years of the “Common Programme” an entirely different impact in the establishment of the balance of forces that the left needed in order to confidently come to power? This factor cannot be ignored amongst the causes, although not the only one, of a historical failure – that of March 1978 – that we have not yet acknowledged.

But other, no less precious, opportunities were missed in the onset of the 1960s, decidedly proximal to our present reality. One such opportunity for the PCF was its becoming a major pole of attraction for French youth. At present, we are a very low level in this respect, if we do not want to confuse hegemony for a conception of a deeply-rooted revolutionary worldview [conception du monde], and the formation of a few meager, though reassuring, fetishes and rituals. Neither the pathetic “Chiffon Rouge” 5 nor the stupefying cult of personality around “Georges” will help us overcome the dismissal we are experiencing, especially among younger workers. But it will not be the anti-drug campaign either, since its targets have been chosen outside of any analysis of the real problem, confusedly and with police denunciation [à coups d’amalgame et de dénonciation policière], stuffing victims and those responsible in the same bag, treating the former as hostages in the competition between political organizations – and here I will not dwell on the cogent arguments concerning alcoholism by the doctors [Paul] Milliez, [Alexandre] Minkowski, and their colleagues, who would be difficult to dismiss as puppets of power. 6

Whether they reject the drugs of violence and despair or those who are tempted by them in a society that is itself sick, our plans and slogans, our organizational methods, when not provocations, appear to these youth as if coming from another planet! In truth – to cite only a recent example, also revealing as a “mass” demonstration – it is with dismay that we see L’Humanité, under the authorized pen of André Wurmser, give a lesson to Roger Ikor, whose son’s death provoked a cry of despair and indignation, by providing him with the example of the Communist Youth – of which I was once a member – mobilized for Health, Order, and Work [Santé, l’Ordre et le Travail] and would have us believe that they are at a distance from all the disorder of their generation…

These youth are of a different age. On the pretext of pulling them away from the bottomless pit of drugs (for how long, and by what means? Is this the actual goal of the operation?), what kind of impasse forces us to take on the responsibility to engage them? And who among us would like to see their children enter the party, exchanging one form of familial paternalism for another, more oppressive and perverse one?

We should recognize that it is a singular societal fact that our language no longer has any hold on “youth” today. Class divisions are not absent, much the opposite. Any teacher or educator can see them today, widening before our eyes. But there is an immense gap between these glaring inequalities in work, culture, and leisure, and “class consciousness.” This gap can leave room for the visibly most brutal and most irrational oscillations, from one extreme of the political spectrum to the other, bringing together, for better or worse. young workers and young bourgeois intellectuals in the same mass thrust: witness May ’68, but also the fascism of yesterday. This milieu accentuates the ideological tendencies ascendant in the conjuncture.

But it also has the surprising property of reproducing a generational memory, beyond the renewal at an individual level. But the youth of the 1960s, those who took part in May ’68, found in anticolonialism and anti-imperialism the reasons for its political engagement: first in relation to Algeria and Latin America, then in relation to Vietnam. It’s clear that in both cases, these youth were profoundly disappointed by the PCF, always systematically lagging behind a slogan or revolution – even though many student militants and young workers would go on to join the party, often for long periods, bringing with them their enthusiasm and desires.

From the Front Universitaire Antifasciste to the Comités Viet-nam “de base,” and the ideological revolt of the educated youth in ’68 and its attempts to join up with, after having provided the initial spark, the largest workers’ strike in French history then in motion (attempts that were certainly aleatory and contradictory, but in which the Party chose to only see the dangerous influence of a “German anarchist,” “gauchos” and other “ultra-leftists”…), this is a distressing story that would be necessary to retrace, without any kind of complacency. I do not wish to preemptively judge it, but I consider it very probable that the destructive effects of nationalism and an anti-imperialism too often more verbal than consequential can be read at every step. Here again, it is a matter on one factor among others, but this demoralization, ideological exasperation [ras-le-bol], and the extinguishing of revolutionary ideas of the youth carried a heavy impact when, throughout the world, liberation struggles had started to fall off and it had become evident that the countries in the “socialist camp,” always given as examples in the “overall positive” balance-sheet, were now caught up in the infernal logic of imperialist they had been fighting.

And, to cap things off, it was in this period that the Party missed the opportunity – as was once again the case in 1968 and 1976, to transform and renovate itself in order to become the “revolutionary party of our time.” An analysis of why would take too much time. Louis Althusser, among others, undertook one a short time ago, offering a critique and showing “what must change” – but has never changed – in the PCF, in a series texts still fresh in our memory and which earned him a flood of insults and calumnies. Two years ago, myself and a few others called for comrades to “open the window” – more shuttered than ever – and tried to do so, as close to the militant experience of communists as possible.

I will only say once more that since the Party is not an empire within an empire, that is, a closed space within French society, miraculously preserved in its nature and history from the changes and crisis traversing that society, the sudden discovery that it is being penetrated and besieged by the worst temptations and resurgences of moralism and racism should not be surprising. The unprecedented crisis of the party, the past several weeks of which have revealed new developments, cannot be seriously considered as an isolated phenomenon. It reflects, in its own way, the crisis of French society itself, which in turn reflects a global crisis that poses grave threats. Against the abstract and voluntarist slogans complacently repeated by the leadership, there is no watertight partition between our surroundings and the currents that carry us. But the theoretical forces and human energies the Party could muster have not stopped weakening from within. They have been systematically discouraged, even persecuted.

This leads us to the “blunders” [bauvres] of Vitry, Montigny-lès-Cormeilles, and elsewhere, which everyone can plainly see are neither isolated nor matters of chance, since the Party leadership covers them and claims them as symbols of its politics, even if it did not plan them according to an electoral calculation of a frightful unconscious. What is clearly expected, then, is the channeling this current of fear, self-defense, and withdrawal into an “every man for himself” attitude towards acquired advantages – which we sense all around us, even among our neighbors, friends, and colleagues, and which has found government backing in the “Security and Liberty” law – to the Party’s benefit during this difficult phase it is going through. On this terrain, the risk of competition between political apparatuses exerts itself.

This resignation, this abandonment to racism and populism, this Peyrefitte-ism of the poor, that suddenly emerges in the light of day with the bulldozer operations, where we have the power, and risk taken without hesitation, to get behind the idea that all North Africans are hard drug traffickers! The party has already taken up [Lionel] Stoleru’s position – at the same time offering him, in what is truly a crowning achievement, the role of “défenseur des immigrés” – that is, his language and his slogan for an immediate block on immigration, without specifying any conditions that would allow for the intervention and expression of immigrants themselves, when it is well-known in practice that this slogan serves to justify all sorts of arbitrary expulsions.

How much time must it take for the Party, in these conditions, to pass to the next stage: “Let them go home, they are taking away our jobs”? Here and there, one hears the rumor – the consequences are already being drawn out. Even if this means having to use as an alibi, and to calm the emotions elicited within the party ranks, the exemplary struggle of a Moussa Konaté, or the aid collected for the victims of the El-Asnam earthquake. The gangrene has penetrated, slowly but surely. Once it has bitten, if nothing and no one stops it, then no one knows when it will stop, but it’s clear who will benefit: if it is a matter of mobilizing nostalgic watchwords like “France for the French” [la France aux Français], others are better equipped and have better credentials to do so than the communists. Their posters are already on the walls.

The problems of coexistence between ethnic communities and between generations, problems of housing, social security, cultural and sporting facilities [équipements culturels et sportifs] that municipalities in the working-class banlieues face are only too real. For the most part, the complacent censors of the Communist Party give them short shrift, whether unconsciously or impudently. The crisis has intensified these problems, which are deliberately deployed by power politics to greater enforce the crux of the division between workers and popular organizations.

Another reason to refuse to follow the line of the steepest slope; another reason to emphasize everyday collective action – politics in the strong sense of the word. This does not mean “fistfights,” or spectacles or provocations, but politics as organized by people themselves, which draws them away from their isolation and fear, and sustains the patient efforts towards solidarity by militants, educators, and social workers, who do not wait until an electoral conjuncture to struggle. A politics that would favor and develop the autonomous forms of mobilization of immigrants, emerging from their exploitation, their concentration, their communal traditions maintained against all odds.

This raises the problem of “mass action,” about which enough has been said. In this respect, it must be borne in mind that outside the bases that provide its municipal grounding on the one hand, and its leading influence within the trade unions, especially the CGT, on the other, the political strength of the PCF is virtually nil. Both are incontestable gains from the class struggle, indispensable means of defense and struggle in a conjuncture of crisis, where workers are shouldering the costs and day after day unemployment and a not particularly “modern” form of misery are growing, and which has not encountered until now any kind of adequate, united collective resistance, opening up political perspectives.

But the CGT, which has spoken of these “regrettable incidents,” instead of denouncing the danger, sent a member of its confederal bureau to the shameful demonstration at Vitry, organized by party leadership to lend unconditional support to the mayor and federal secretary’s initiative. What prevents a “mass-and-class trade union” from asking itself about the contradictions, likely to be heightened, between its activity in the enterprises (for example when it works to unite all workers, French or immigrant, from manual workers to engineers, against a mass layoff decided through the framework of “industrial restructuring”) and the antagonisms it aids in deepening around the residential areas [lieux d’habitation]? Is it not precisely by resisting the splitting of man as worker and the “concrete” man of everyday life that class unity ceases to be a theoretical abstraction? And is this not precisely the mortal danger, and thus the practical challenge thrown up by the crisis of the workers’ movement?

And here the communist municipalities – or rather some of them – that have come to grips with paying the cost of the rupture of the Union of the Left in the 1983 elections, are increasingly tempted to seek out a new electoral base by exploiting the fears and prejudices they feel cannot be combated. By what unfortunate “chance” must this temptation coincide with a just struggle for the popular exercise of the right to vote (and inclusion on voter rolls) and subsequently have its meaning diverted – while compelling the President of the Republic to unmask the few cases in which they practice the constitutional principles they claim? What a waste of the efforts of militants, ambushed [pris à revers] once again by their own leaders!

How many communists of Charonne are there today in the PCF’s ranks, who took part in the struggle and conviction of those who died on February 8, 1962, who can compare the reasons for our commitment and our perspectives in the past with those of today, so as to draw the necessary lessons? Increasingly fewer, no doubt, since the way of life [règle de vie] of a party without critical memory, in which the co-opted leaders only talk amongst themselves, is now an accelerated “turnover” in numbers. Those militants without whom, in the difficult years of the past, the party would neither have a mass audience nor the capacity as an organization of struggles, we shed without regrets or scruples, whether they leave themselves or whether, as holders of a symbolic card that no longer gives them any rights except to pay dues, they remain at home in the improbable expectation of a sudden resurgence – or whether yet they are expelled in a hypocritical manner, since to critique a line over which they have never had any say in orienting, elaborating, or carrying out is today called “putting oneself outside the party” (look for the corresponding article of statutes).

Increasingly few, but certainly far from zero. One such example is the way in which our comrades in Rennes collectively forced an overzealous federal secretary to back off in a dispute over an Islamic cultural center. We all know similar types of militants. But they have a task ahead of them, as do our younger or older comrades for whom the contradiction between the declared principles and goals and the effective practices have passed beyond what can be supported, and who refuse, by all possible measures, the individual solution of departure or silence. A major social crisis, like the one we have already been experiencing for several years, always leads to transformation across all social classes: conditions of life, conditions of work, ideologies and “mentalities,” representative organizations.

Whatever it can throw up to escape this crisis, the communist party will not emerge unscathed. Faced with a working class that less and less resembles dogmatic Marxist stereotypes, the self-proclaimed politico-ideological monopolies will end up shattered into pieces. And all for the better. But that does not mean that workers will be able to dispense with existing organizations. Collectively, they do not have ideal free choice. If they want to defend themselves, they will be forced to impose a progressive outcome to this crisis themselves; they cannot engage in a politics of the worst, nor start over with a clean slate. Therefore, party and class will change together to a significant degree.

But in what direction? There is no predetermined end, only more or less unfavorable material conditions. It is up to us, communists, to put a stop to the double spiral that leads, on the one hand, a fraction of the working class and petty bourgeoisie towards a defensive, corporatist, xenophobic, and moralistic ideology; while, on the other, the party (along with the CGT, unless this shift, which has already caused it to lose hundreds of thousands of members, does not lead to its disintegration) would provide this historical regression with the cover of a “revolutionary” phraseology.

I am publicly posing the question to my comrades in the party, militants and officials: are you going to believe in this inevitability, and let yourselves slide down the slope? Is it impossible to draw lessons from the history I have just recounted in broad strokes, to establish another politics, whose class bases have always existed, even if it means harsh revisions and bitter trials, as was the case for other examples which swam against the current [ramer à contre-courant]? Is there really no alternative in the enterprises and the low-income neighborhoods other than passivity or alignment with ruling class ideology and methods? Is it necessary for us, in our ranks, to prevail, without debate nor struggle, against the line and practices of the communists in Vitry and their emulators across all levels of the Party, which over several years has institutionalized a double language and monopolized power through barely disguised factional methods? Perhaps we shall know before too long.

– Translated by Patrick King

This article first appeared in Le Nouvel Observateur, no. 852 (March 9-March 15, 1981): 56-60.

The translator wishes to thank Joseph Serrano for his helpful comments on earlier drafts.

References

| ↑1 | A militant in the PCF and CGT, from Mali, who was a leader [responsable] of the Syndicat des Grands Magasins, and whose deportation order by the Barre government was canceled after several weeks of mobilization. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Secretary of the PCF Federation of Val-de-Marne. |

| ↑3 | The Communist mayor of Vitry, who helped a public works bulldozer drive into the entrance of a house where Malian workers had settled, against the opinion of the municipality. |

| ↑4 | The Communist mayor of Montigny-lès-Cormeilles (Val-d’Oise). In the context of the PCF campaign against drugs, he publicly decried the young Moroccans living in the city as “dealers.” |

| ↑5 | Translator’s Note: Balibar is referring to the song “Le Chiffon rouge,” written in 1977 by Maurice Vidalin, but sung and popularized by Michel Fugain. It was a mainstay in the social struggles of the PCF and CGT in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, and its lyrics contained misérabiliste accents, in line with the PCF’s political discourse and working class strategy during this period. Thanks to Julian Mischi for the precise reference. |

| ↑6 | TN: In 1981, Paul Milliez, a doctor known for his political engagement, headed a commission on criminal justice and victim rights, which suggested to the Minister of Justice greater resources be devoted to crime victims, and a more restorative policy model be introduced. |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine