[This essay is an excerpt from Evan Calder Williams’ new book Shard Cinema, out now from Repeater. 1 Another brief excerpt, and longer description of the book project as a whole, can be found at The New Inquiry.]

--

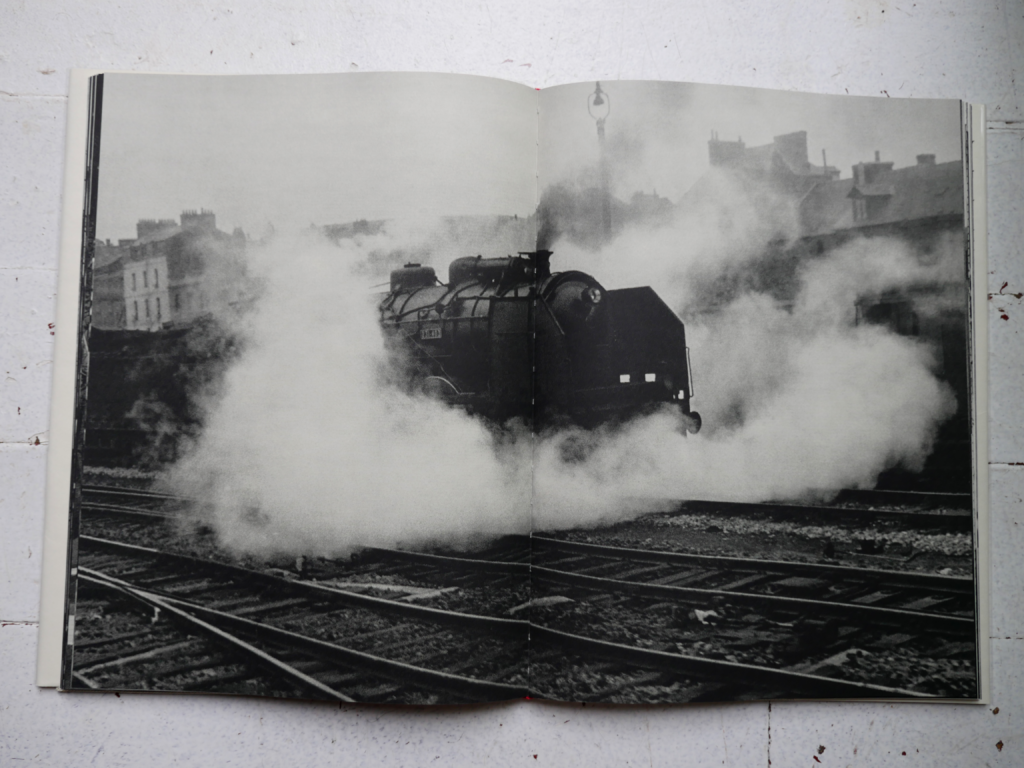

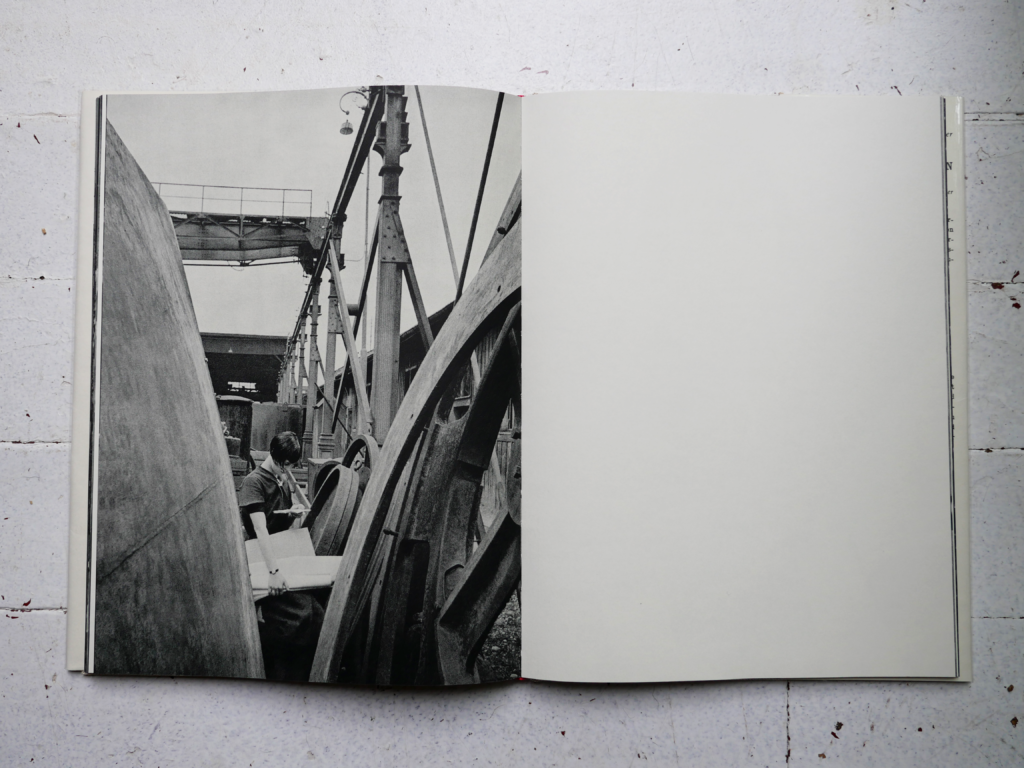

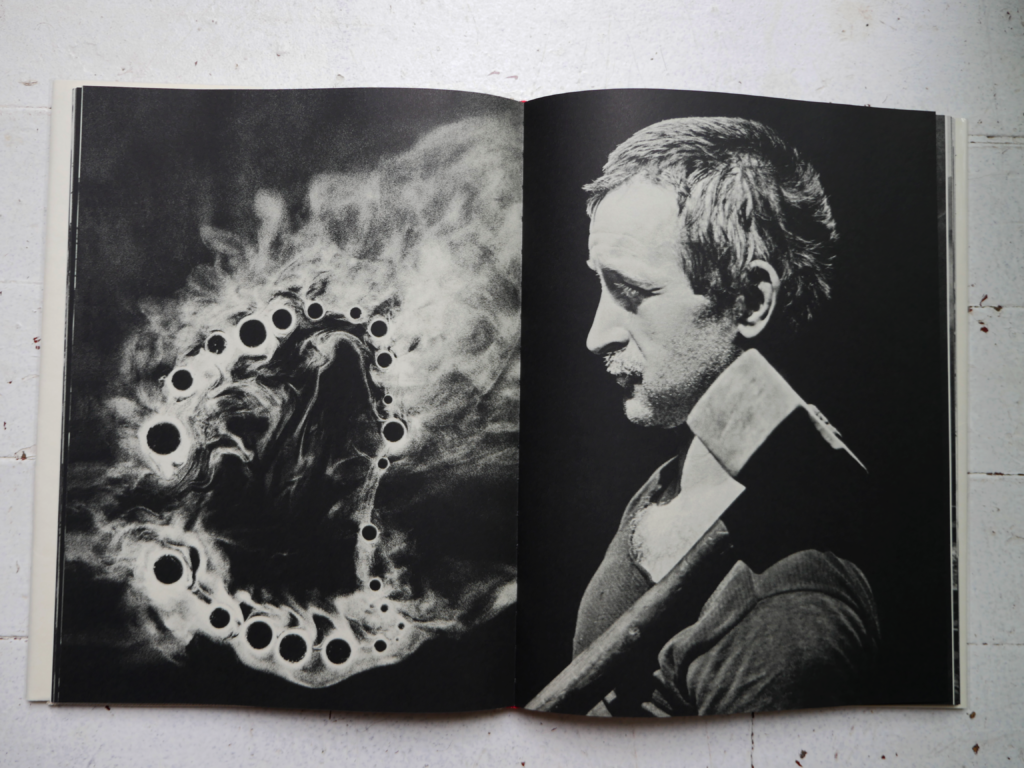

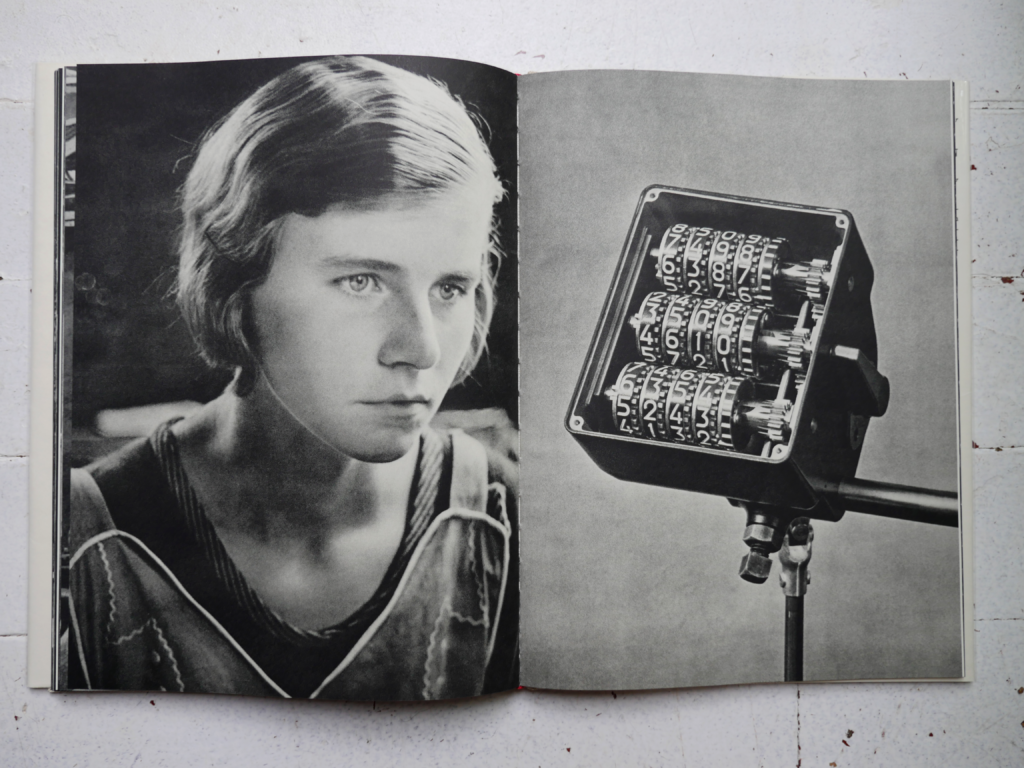

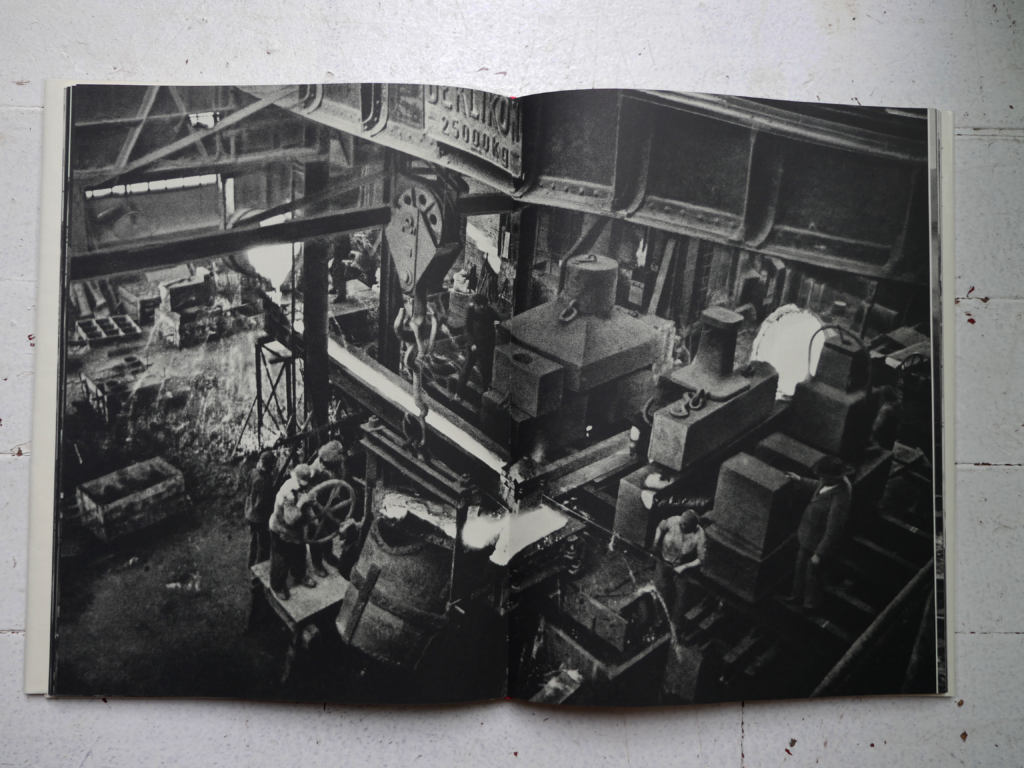

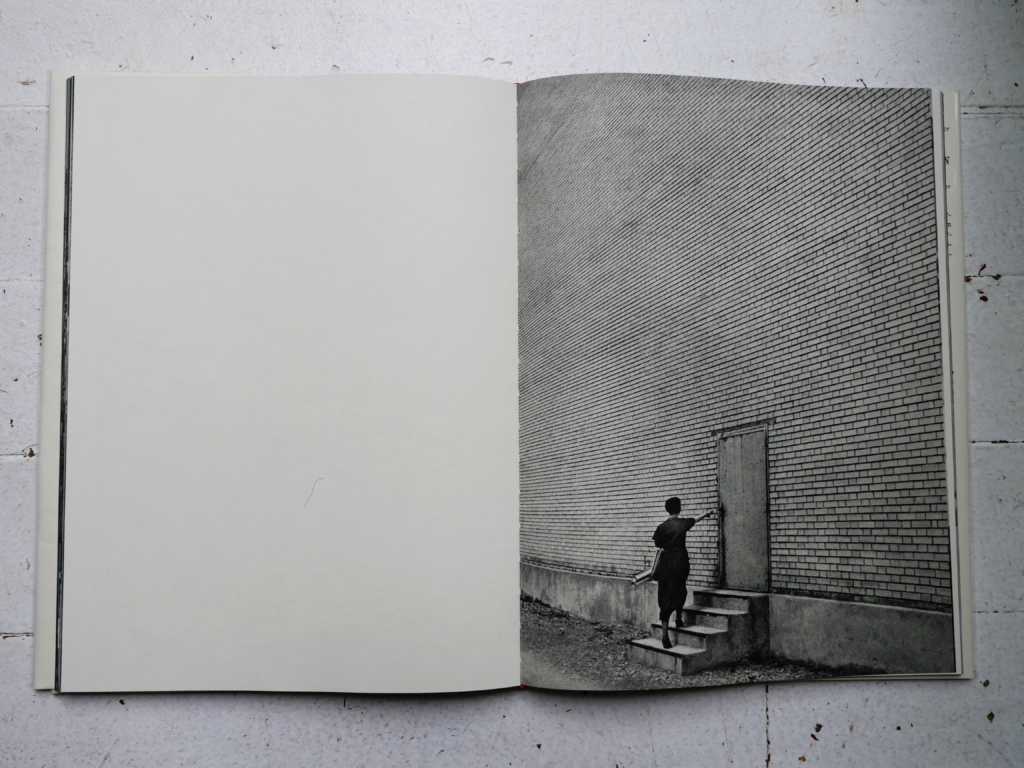

from Jakob Tuggener’s Fabrik

There’s a fundamental tension at play in how we think about the emergence of new technologies, especially those so significant that they seem to rewire the very paths and categories we use to navigate the world. From a distance of decades or centuries, when one might try and draw a clear divide between before and after, a common temptation is to focus on that initial contact when a typewriter, car, mechanical loom, indoor toilet, or television is first glimpsed and used, the uninitiated gasping in wonder at the alien novelty dropped as if from on high. According to this schema, the shock is one of the truly new, the exotic, and the exceptional, an essentially modernist and colonialist 2 fantasy of a technological event that interrupts and abolishes what is suddenly outmoded, like Marinetti’s self-mythicized 1908 car crash or the Lumière brothers’ train racing toward the screen and blowing the minds of a panicked audience unprepped for anything of the sort. 3

Allegedly blowing the minds, that is. Because as far as we can tell, no one ever actually ran from that infamous steam engine – the one in Train Arriving at La Ciotat and hence at the supposed origin point for cinema, at least in terms of the first screening for which people paid. 4 In existing accounts of the 1896 screenings of that film, that mythical moment of panicked belief – as the train threatens to roar through the screen and smush the audience beneath spectral wheels… – never appears. 5 However, this only amplifies its significance as a twinned myth of progress and obstinacy, because it indicates the anxious urge for the story to be true (and, in other moments, a vested interest in it being otherwise). 6 Moreover, as much as it has been endlessly rehashed, it can’t be fully set aside, as it still informs how we work with and against images: in part because it names the inanity of dividing between representations and things, in part because debates over the story became foundational to film history and theory, as in Tom Gunning’s 1989 essay on the matter.

In that essay, Gunning works to dismantle three distinct inheritances: the story itself, the commonplace explanation (i.e. the naive viewer who mistakes the train as real and/or generally freaks in the face of advanced tech), and the “admirable subtlety” of Christian Metz’s structuralism-on-overdrive take on it. For Metz, the story, however false, was bound to be blown out of proportion by later spectators – by us, by all of us, you can feel Metz chiding – who use it to disavow our own latent credulity in images through insisting on a historical gulf separating they who shrieked from we who smirk. But this disavowal is made necessary by the fact that it must remain incomplete, because, in a fittingly horror-film twist, the sophisticated spectator can never truly get rid of the naive believer. That believer is “seated beneath the incredulous one, or in his heart,” some parasite of blind faith waiting to gnaw its way out of Enlightenment and into blinking day. 7

Gunning provides what remains an important rejoinder to this, not because “we” do or do not believe but because Metz’s version reaffirms a position that is just as ahistorical as the false image of the howling crowd. “Removed from place and time,” Metz’s model reduces the early film spectator into “a projection of an inner deception onto the mythical site of cinema’s ‘once upon a time” (the kind of maneuver one finds, for instance, in Jean-Louis Baudry’s analogy between Plato’s cave and the cinema). 8 What Metz misses, according to Gunning, is how neither the film nor the spectator was ever timeless or without predicate, never some transcendental ideal of viewing at its primal source. The spectators who came to those screenings did so in a context already thick with screens, composited images, animations, and optical tricks. Those sites of viewing were already suffused with dynamics of gender, race, and class expectations that delimited the public space of the screening and that worked to differentially determine the experiences of who was watching and how they were watched in turn. Such policed expectations would be continually transformed and fought over in the next two decades, by those who found ways to subvert the demanded uses of such a space and by the owners and theater operators who sought to turn the cinema into a bourgeois institution free of booze, public sex, and generally raising hell. 9

With a thicker media context restored, a different bunch of giggles, gasps, and shudders comes into view, especially when we remember, as Gunning points out, that the train was not presented as a moving image from the start. Instead, the screenings provided an object lesson in the medium itself: they started with the film’s first frame projected as a still, then began cranking it into motion. To start with a still image was crucial, because it engaged already-established familiarities with this new medium and used them to produce its shock. For instance, at a similar screening, Georges Méliès himself started to complain to a friend that he had “been doing [still projections] for over ten years,” before the projectionist started to crank the film, and the image slowly groaned into “all the animation of the street.” 10 Then, and only then, came those slack jaws, “astonished beyond expression.” Far from being naive viewers, the audience was already too canny, already up on, if not yet bored by, what to expect at such screenings. In that way, the real astonishment was neither befuddlement at the capacity for technical movement nor confusion about just how much a projected train can maim. It was a dislocation of slowly accreted media expectation, and it was an experience of gesture as such, a medium coming into view by revealing the process and limits of its construction.

We also have to note how quickly that supposed blow to cognition became available for a gag, like in Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show (1902), where the titular character is a country “rube” who doesn’t know any better, jumping in mock horror away from the screen’s approaching train – though not before getting in the way of the projector beam and goofing off for the audience, with no evident fear for his life. The fact that this works as a gag suggests a different kind of technological shock, one at work not when we allegedly shit ourselves in terror at a projection mistaken for a window, but when, in the space of only a couple of years, that same experience can become that fable of our old naivety, the outmoded viewer as rube and yokel all agog. Its shock is retroactive, then, and finds us split in time, divided by what has come into the world, as the way we used to be gets corralled into some prelapsian before, our anxieties left behind for archive or gutter or an over-cranked gag reel.

What’s especially important about Uncle Josh playing the fool is that this velocity of a shift to the familiar, with a slim four years separating the two films, suggests a timescale at fundamental odds with that of absolute novelty, yet which comes far closer to the everyday experience of it. Because when we live through these emergent media and technical forms, we don’t experience them as bolts from the blue. 11We detect them as a creeping sensation, as we become gradually strange to ourselves, accustomed to profoundly different relations of space, sight, time, and body without ever feeling the shift itself suddenly click into place. Real shudders of novelty take shape retroactively, as aftershocks, when a form becomes naturalized, expected, and unthought to the point that we feel alien to ourselves only without it. It becomes part of our extended assemblage, and we type without looking, reach over the pillow for glass bedmates, and arrange faces into vector planes before the camera flashes. Only then do we fully feel the interval between ways of life, there at the point just before invisibility, its last moment of appearance before it dissolves into normalcy and what isn’t even worth commenting on.

--

As scholarship gathered under that loose banner of media archaeology has done a crucial job of pointing out, it wouldn’t make sense to see such shifts as the result of a technology, given that media forms themselves draw omnivorously on disparate techniques and available procedures, just as we who engage them are slowly constituted by histories that exceed the narrower ambit of the moving image or the touchscreen. In this regard, the hint that Giorgio Agamben provides in “Notes on Gesture” is a compelling if incomplete one. There, in trying to situate the terrain of the early twentieth century, he suggests that “An age that has lost its gestures is, for this reason, obsessed by them.” 12A gesture, for Agamben, isn’t a means to an end, a successful supplement to language or a movement that enacts or communicates: it is instead “the process of making a means visible as such,” a gesturing that always points back to the limits of communication itself, that “muteness inherent in humankind’s very capacity for language.” 13 In this case, he also means something more tangible: the tics and frantic gesticulations that mark both the clinical “discovery” of Tourette’s and the staccato, flailing movements of early film actors. His argument is that during the massive cultural transformations gathering force in the Global North by the late nineteenth century, the understanding that individual experience might be communicable or that gestures had a stable grounding breaks down. As a result, “the more gestures lose their ease under the action of invisible powers, the more life becomes indecipherable.” It is this situation that cinema inherits, as in these films “a society that has lost its gestures tries at once to reclaim what it has lost and to record its loss.” 14

Whether or not one is convinced by his account, there’s a strange absence worth noting. In detailing just what marked that slow loss of gesture (other than the “action of invisible powers”), the only concrete references made are to clinical psychology and to breakdowns depicted in, and within the formal structures of, bourgeois subjectivity and culture. 15 What never get mentioned in this essay are the drastic shifts in gesture, motion, meaning, and selfhood that more and more of the world’s population underwent in the century prior to cinema: mechanized work and the emergence of the factory system. This omission might not be especially significant, particularly given the scope of Agamben’s work and its relative disinterest in labor history, were it not for the fact that it is incredibly common. In the majority of influential and compelling histories of the emergence of mechanical moving images, the factory goes just as markedly missing. 16

This signifies something worth pausing over: that accounts of what cinema might have meant, or might come to mean still, will turn their backs again and again on a form of intelligence, awareness, and contestation that did not come from bourgeois crises about the character of the human. It came instead from the experiences of those who worked in the factories and were forced to learn to become inhuman – to experience the concrete shattering and reconstitution of their gestures, to live through the difficult necessity of trying to make sense and sight of this new order and its distributed violence that their labor animated.

--

While factory apologists propagated accounts of child workers literally whistling while they worked, reformers and workers in Germany, Britain, France, and the United States framed this experience of mechanized work as a specific threat to the coherence of the human. An especially common variant was to focus on how the monotony and fatigue of such work might generate “bitter recriminations against the social order” (i.e. revolts) and threaten to erase the line that separates “the brain of the civilized from that of savage man.” 17But as the dual reference to the insurrectionary and “the savage” suggests, any attempted universality of claims about human nature was undercut by historically-specific social anxieties, especially as the labor itself was read as the bleeding edge of some serious gender trouble. (Including from those in favor of the extension of such work, as champions of mechanization hoped that rigorous and exhausting employment might help ward off bands of dissolute, unwed, and recently proletarianized women leaving farms to come walk the city streets.) In particular, such mechanized work was thought to destabilize the way that technical knowledge and capability was held in the body of the craftsman who displayed mastery over his prostheses, his tools. For instance, in German studies of die Schrecken des überwiegenden Industriestaats (“horrors of the industrial state”) that concerned work where both the human and the machine are mutually prosthetic for each other, the panic becomes unmistakably gendered: as the hand weaver transitions to a “technological weaver,” he is “transformed from a master into a hired hand [Handlanger], from a man into a maiden.” 18

In short, even as claims about machine experience address themselves to the idea of the human animal as such, they will be relentlessly worked out in terms of what it does to the stability of gender roles and family structure: specifically, to what guarantees the reproduction of those humans available for waged work and who gets tasked with it. 19But this isn’t just a side effect of the slow formalization of specifically capitalist modes of gender control. It’s also because one of the fundamental characteristics of increasingly mechanized work was to confound the boundaries between the production of goods for sale and the reproduction, care, cleaning, and maintenance of the hybrid systems involved in that making, the most replaceable parts of which are human. The monster must be mothered by someone, after all. As Lucy Larcom, a child worker in the Lowell cotton mills, would write later of the machine she tended:

Mine seemed to me as unmanageable as an overgrown spoilt child. It had to be watched in a dozen different directions every minute, and even then it was always getting itself and me into trouble. I felt as if the half-live creature, with its great, groaning joints and whizzing fan, was aware of my incapacity to manage it, and had a fiendish spite against me. I contracted an unconquerable dislike to it; indeed, I have never liked, and never could learn to like, any kind of machinery. And this machine finally conquered me. 20

As Larcom’s description suggests, that language of monstrosity isn’t my own recasting of industrialization in horror-flick terms to match Metz’s parasitic demon of faith. It was one of the most common modes of depiction from those who witnessed and worked amongst these transformations. Diaries, inquiries, sermons, and broadsheets bristle with these “half-live creatures,” demons and “rattling devils,” “little hells” and tongues of flame, soundless “giant levers” that heave “upwards once in half a minute with a slow motion, and seemed to rest to take breath at the bottom.” In these texts, factories “burst in our view […] as though by magic.” 21 “Had our ancestral grandmothers witnessed the antagonism sometimes manifested by machinery,” one woman writes, “they would have pronounced it bewitched and punched it with red hot irons.” 22

Yet if the broadly supernatural and primeval language gives one indication of how little frame of reference workers had for what awaited them in the mills and workshops, the structure of such writing itself belies this lived category error all the more, as it searches relentlessly for adequate comparison but settles on none. In a single paragraph from British ecologist Richard Jeffries, for example, a metal works is described as a “vast incongruous museum of iron”; Proteus, the shape-shifting aquatic god; a “vast wilderness”; “a temple of Vulcan”; the heavens, as “the sparks fly in showers from the tortured anvils high in the air, looking like minute meteors”; and, above all, the figure underwriting not just his but so many nineteenth-century descriptions: Pandemonium and Hell itself. 23

One might blame this breathless swapping of site and sense on bad writing, at least according to some MFA swill about the dangers of mixed metaphors. That would wholly miss the point that, like Larcom, Jeffries is grappling with a terrain that had yet to become a texture and fixture of daily life, not yet available to be conjured in a reader’s mind with the words the factory, the mill, the assembly line. So as David Zonderman suggests, this “cultural or conceptual lag in the language” makes sense, because “there were no terms of reference readily available to describe labor that produced no sweat but was nonetheless exhausting.” 24 The only language ready at hand had been forged by grappling with a different mode of work, one where movements don’t have to match their rhythm to a lurching synchrony of metal and force, and where it might be maintained with some degree of plausibility that it is you who hold the tool – and not vice versa.

--

But what exactly did Larcom mean when she wrote that the “machine finally conquered me”? It isn’t that she grew to like her “overgrown spoilt child” – she’s writing decades later and still “never could learn to like […] any kind of machinery.” Conversely, it would be wrong to see it as a simple domination, of being bested by and made subject to. In an anonymous 1844 letter signed as the “Lowell Factory Girl,” a more triumphal account of mechanized work’s liberating potential, the author claims that she was “allowed to make more and more money, by the accommodation of the speed of the looms to my capacity.” 25 Whether one’s pace was met or dictated by the machinery, the crux is that one adopted a set of rhythms and gestures that weren’t operative before and only make sense within a total assemblage that’s simultaneously mechanical and human. In this space, concepts and explanations find themselves outpaced not just by the manifest strangeness of a situation but also by one’s own physical self, the fingers forced to quickly figure what the mind doesn’t yet know it knows.

All gestures are perhaps inhuman, because they enact that hinge with the world, forging a bridge and buffer that can’t be navigated by words or by actions that feel like purely one’s own. In Vilém Flusser’s definition, a gesture is “a movement of the body or of a tool connected to the body for which there is no satisfactory causal explanation” – that is, it can’t be explained on its own isolated terms. 26The factory will massively extend this tendency, because the “explanation” lies not in the literal circuit of production but in the social abstraction of value driving the entire process yet nowhere immediately visible. We might frame the difficulty of this imagining with the concept of “operational sequence” (la chaîne opératoire), posed by French archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan, which designates a “succession of mental operations and technical gestures, in order to satisfy a need (immediate or not), according to a preexisting project.” 27 In archaeological terms, operational sequences function as total maps of how materials and processes are shaped to human ends, zooming out, for instance, from a single chipped stone arrowhead to the gesture needed to strike it, the gathering of the stone, the construction of the tool used to hammer at it, the wood, the fire, the food consumed to have the energy to raise the arm… and out from there. In short, the operational sequence moves us away from excessive focus on the visible moment of production to an obscure but still material network, one whose juncture points are each constituted by a distinct gesture that alters the material moving through the web. These gestures form the essential pivots of the chain, crystallizing a social intelligence only in view when taken in aggregate. It impels us to look far beyond what appears to be the purview of a site of production, like the factory, toward the full network that folds in the slave labor that provides the cotton, the logging and carpentry that makes the looms, and the homes where the workers are cleaned and rested and cared for by mothers, partners, and friends.

Obviously, we’re far from the only organisms to be characterized by this transformation of materials to our ends. (The nests of birds, the burrows of badgers, the mycelium network under the forest floor, the hives of bees…) For Leroi-Gourhan, the difference is that rather than genetically internalizing our species memory as instinct, we externalize our memory of how to gesture and interact with the world, as “only with humans do we see these operational sequences take material form and become more-or-less permanent constituents of the human environment.” 28 In this way, we evade “organic specialization” in favor of a biological non-adaptation, as our prostheses allow us to shapeshift across forms – “a tortoise when we retire beneath a roof, a crab when we hold out a pair of pliers” – and construct a materially transformed world in order to match our needs (or, perversely, to make them impossible to meet). 29

Which is to say: we build factories. And in those factories, the process of the exteriorization of memory and muscle becomes almost total, as “the hand no longer intervenes except to feed or to stop” what Leroi-Gourhan, like Larcom, will call “mechanical monsters,” “machines without a nervous system of their own, constantly requiring the assistance of a human partner.” 30 But along with engendering the panic of becoming caregiver to the inanimate, this also poses the problem of animation in an unprecedented way. Because if a “technical gesture is the producer of forms, deriving them from inert nature and preparing them for animation,” the factory constitutes us in a different network of the animated and animating. 31 It’s a network that can be seen in those writings of factory workers, with their distinct sense of not just preparing those materials but becoming the pivot that eases, smooths, and guides the links of an operational sequence. In particular, a worker functions as the point of compression and transformation between tremendous motive force and products made whose regularity must be assured. The human becomes the regulator of this process, the assurance of an abstract standardization.

Because as has long been observed, the point of a factory is to produce not only goods but also the persons involved in the process, to enforce and naturalize a lived category of abstract labor. This is captured in a startling poem from Larcom, as she zooms back, as if a floating camera, from her place at the loom to the entire setting:

And in a misty maze those girlish forms,

Arms, hands, and heads, moved with the moving looms,

That closed them in as if all were one shape,

One motion… 32

The ability to pull off that move isn’t just a mark of her capacious imagination and lifetime of experience in the mills. It is also part of what the factory means and meant, both the sensation of getting folded into a scattered, synchronized web of gestures and the material production of an image of this process. If any operational sequence forms a map of how gestures are never singular, always just one junction in a dizzying collective interchange of action and substance, then the factory has the distinct capacity to make this evident in any given moment. It is a freeze-frame unmistakable to those involved in it, compressing the whole sequence in miniature into a single “misty maze.”

--

However, if the factory sculpts a physical diagram of these disparate forces, the literal images of them made in the nineteenth century, whether by human hand or with camera, showed themselves distinctly resistant to grappling with this tangle of gestures. A Giovanni Migliara painting from 1820, The Sala Silk Factory at Castello di Lecco, shares some of Larcom’s pull backwards, depicting a factory floor receding away from us, its high timber ceiling angling in linear perspective, matched by the bobbins below. But unlike Larcom’s writing, which passes from intimate knowledge of the process to this removed position, the spate of paintings, etchings, drawings, prints, and photographs made of such spaces in the nineteenth century follow Migliara’s lead: they keep their distance. With few exceptions, all share that same perspective, raised above the floor and angling down, so that the space is both expansive and yet manageable, architecture and machine and worker all present but never commingled or up close, looking down at the blur of chaff and solder and fingers. This holds even in the rare canvases willing to show the worksite as a sputtering hell, like Adolph Menzel’s Iron Rolling Works (1872-75).

Later photographs, like those of Lewis Hine, capture some of the mess, at least at break time, while Jacob Lawrence’s remarkable 1960s studies of a textile mill in Bedford, Massachusetts, forge a scattered graphic dissolution of elements into a chaos where bodies and looms alike are open volumes and ragged lines. But in the images made in the years when this was creeping into prominence as a lived reality across Europe and North America, the distance remains. It is the perspective and position of the boss, he whose hands never enter the frame of the loom, whose gestures are not remade in the process of making. The only trace of such entanglement that appears in these images and photos is the rare presence of the scavenger, the child worker who crouched beneath the threads, body ghosted white by the interference. Above them, the machines seethe and do not rest, leaving stray fibers and dust to be snatched and cleaned, the small proof that they too generate friction, that even what will mangle a hand must still be tended to.

--

If cinema steps into a world shaped by “invisible forces,” it isn’t because those forces are immaterial or purely conceptual. It is because they confounded any such possibility of critical distance, demanding that thought confront abstractions on the ground and alienation in the flesh, produced physically and tangibly in the repetition of gestures. The factory itself, and the forms of intelligence and resistance gathered there, will prove doubly resistant to imaging because it already is an image of itself, a material diagram of flows drawn by the workers who are necessary for its motion but always fungible, always subject to replacement. This is the lived terrain that cinema takes shape in and draws its force from. And unlike the impasses that still images kept hitting when trying to depict the factory, cinema will be able to do something particular with that motion, in no small part because it makes it possible for vision to literally track from that distanced view to the close-to-hand. It can bring the farthest-flung paths of the operational sequence into montage’s proximity, from the mine to the machine, the plantation to the bank to the bed to back again, even if it too rarely makes use of this ability, even – or especially – still.

A full exploration of how moving images both open up this possibility and yet consistently miss their chance to explode the diagram is for another essay, if not a whole other book. Instead, what I’m sketching here in this passage through scattered materials of the century prior to filmed moving images is something simpler, a small corrective to insist that by the time cinema was becoming a medium that seemed to offer a novel form of mechanical time, motion, and vision, one that historians and theorists will fixate on as the unique province and promise of film, many of its viewers had themselves already been enacting and struggling against that form for decades, day in, day out. The point is to place the human operator back in the frame, to ask after those who tended the machine before it was available as a spectacle, and to listen to how they understood what they were tangled in the midst of. But this is neither a humanist gesture of assuring the centrality of the person in the mesh that holds them nor a historical rejoinder to the forgetting and active dismissal of many of these personal accounts. Rather, it’s an effort to show how only with the operator’s experience made central can we see the real historical destruction of such illusions of centrality and, in their place, the novel construction of the human as tender and mender of a flailing inhuman net, the pivot who forms the connective tissue that enacts the lethal animation around her. In short, to see how the real subsumption of labor to capital is not only a systemic or periodizing concept that marks the historical transformation of discrete activities in accordance with the abstractions of value. It also is the granular description of a lived and bitterly contested process by which those abstractions get corporally and mechanically made and unmade, one which we can understand differently if we shift our angle from the boss’ POV to those unable to get any respite or distance from the situation.

To come back to that infamous projected train, I have no doubt that many viewers of the first photographic moving images gasped and marveled at them, if only because I know how often I do the same 120 years later. But the marvel isn’t and wasn’t because the technology feels alien or provides a magical reconstitution of halted life or offers an unthinkable shock of the new. It’s the inverse of that. It’s because it is made from the same circuits and paths – in and out of the animal, the mechanical, the calculated, and the contingent – that constitute not just everyday life but many of its most crushing forms. In this sense, I think it was and remains right to speak of the “magic of cinema,” just as it made total sense to speak of power looms as demons beholden to an infernal project. After all, both claims begin with the complication of, and a subsequent refusal to flee from, the limits of gaining that clear critical distance. Both admit what it is to be too close and to be unable to begin otherwise, to wish it away. In that sense, the magic of cinema is that it gave image not only to but also through these animated sequences that had proven so hard to imagine and had so frustrated available language and style even as they slowly remade what it meant to see and to move, erasing the borders between a self and a world with a vested interest in reaping the profits of that erasure.

References

| ↑1 | A short, early version of this essay first appeared in the Lucy Raven: Edge of Tomorrow, a catalogue accompanying the exhibition of the same name at the Serpentine Gallery. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a classic but still essential study of this dynamic, see Michael Adas’ Machines as the Measure of Man: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989). |

| ↑3 | The film would be reshot in 3D four decades later and screened at the French Academy of Science in 1935, where that imagined moment of the train “coming through the screen” finally got realized, at least stereoscopically in negative parallax. |

| ↑4 | And in many ways, it isn’t wrong to identify that as a beginning, given cinema will be so much about that problem of how to economically animate the already built, the already screened and seen. |

| ↑5 | As Ben Singer draws out in Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and its Contexts (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), these same years would be full of spectacles that came much closer to this threat, in stage-spectacle melodramas full of live horses, buzz saws, and, “real fire engines, real patrol wagons and real locomotives” (in the words of a brilliantly acerbic 1894 review of a stage melodrama that “was evidently written to appease the yearning among playgoers for a drama with a real steam pile-driver in it”) (p. 51). Singer also details a 1906 play that featured, in his words, “a four-way race between two automobiles, a locomotive, and a bicycle, as well as a motorboat race, fire engines speeding toward a burning building, and various torture scenes” (p. 152). |

| ↑6 | What Furio Jesi would call a “technicized myth,” following Károly Kerényi: a myth that has been taken out of spontaneity and change, fixed, and pressed into service of a larger historical-narrative assemblage. See: Furio Jesi, Spartakus: The Symbology of Revolt, trans. Alberto Toscano (London: Seagull Books, 2014). |

| ↑7 | The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), p. 72. |

| ↑8 | Tom Gunning, “An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator,” in Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film, ed. Linda Williams (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1995), pp. 115-16. |

| ↑9 | One of my favorite texts on these shifts is undoubtedly The Perils of Moviegoing in America: 1896-1950, by Gary D. Rhodes (New York: Continuum, 2012), which exhaustively details ticket money theft, in-theater sex work, the legitimate fears of projector fires, and a whole slew of other “perils” (real or perceived) that shaped what came to be understood as the space of spectatorship. Another crucial text on the specificity of Black early cinema experience, set in the wider context of urban transformation (especially Chicago’s Black Belt movie theaters) is Jacqueline Stewart’s Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Urban Black Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). |

| ↑10 | Ibid, pp. 118-19. We should note also how much the entire experience shares with, and draws from, other available media. Its novelty only works because of audience familiarity with projected photographs in magic-lantern shows – the gag is to have that still start to move. It also shares a gesture with personal modes of moving-image viewership, like the Mutoscope. As Erkki Huhtamo notes, such cranking is “actually not so far removed from that of (male) Mutoscope viewers who would arrest the reel to have a better look at a ‘particularly interesting frame (perhaps a half-naked lady)’.” Erkki Huhtamo, “Slots of Fun, Slots of Trouble: An Archaeology of Arcade Gaming,” in Joost Raessens and Jeffrey Goldstein (eds), Handbook of Computer Game Studies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), p. 9. |

| ↑11 | The major exceptions to this timescale are military technologies as experienced by those in zones where such weapons haven’t previously been deployed, like that of napalm in Vietnam, for which there were no equivalent experiences. |

| ↑12 | Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture,” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), p. 53. |

| ↑13 | Giorgio Agamben, “Kommerell, or On Gesture,” in Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), p. 78. |

| ↑14 | Agamben, “Notes on Gesture,” p. 53. |

| ↑15 | This skewed causality haunts other accounts that draw on Agamben’s essay in order to give related theories of fin de siècle shifts in human perception and experience. For instance, in Pasi Valiaho’s Mapping the Moving Image: Gesture, Thought, and Cinema Circa 1900 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), a compelling (and hyper-Deleuzian) account of rhythm and early cinematic gesture, he inverts the causality latent in Agamben’s argument to argue that, “these nervous gestures are not solely a matter of medical history, but more fundamentally, also embody changes in our cultural being brought about by cinema” (p. 17). |

| ↑16 | It is a genuinely widespread omission. Consider the aforementioned Valiaho text, for instance. Given how Deleuze-inspired it is, the book is expectedly full of machines, both literal and figurative. We get hints of automata and important suggestions of how machinic encounters create “a zone of indetermination or indiscernibility between spontaneous and automatic, the living and the machine” (p. 27). There are “graphic self-recording machines” (p. 34), simulation machines, machinic understandings of the body, a tachistoscope, Freud’s understanding of the psyche as a machine that “in a moment would run of itself,” an “interpretive machine,” a desiring-machine, calculating machines, a train, and a ship. But no real sense of the factory: it’s only by way of Gilbert Simondon that we get anywhere close, in the presence of a Jacquard loom. In Lisa Cartwright’s absolutely fundamental work on cinematic imaging, especially in relation to medical and scientific forms of image-production, these “self-recording machines” are set within the larger category of motility, with a particularly sharp grasp of the underpinning shift in pathology and anatomical understanding, that “did not simply uncover but also produced the body as animate, as process incarnate” (Cartwright, “The Hands of the Projectionist,” Science in Context 24(3), p. 445). But there too, the medico-technical and scientific remains bracketed from the factory (or even the industrial more broadly). And this holds in all the major works of Friedrich Kittler, Siegfried Zielinski, Giuliana Bruno, Charles Musser, Mary Ann Doane, and others. In all, a significant investigation of the way in which factory experience had shaped the audiences who came to watch is thoroughly missing, even as the same texts suggest at length how the cinematic apparatus itself echoed the machinery of mechanical reproduction, warfare, medical treatment, transportation networks, and scientific experimentation. |

| ↑17 | Angelo Mosso and Marius Carrieu, both cited in Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (New York: Basic Books, 1990), pp. 43 and 38. |

| ↑18 | Robert Wilbrandt, quoted in Kathleen Canning, Languages of Labor and Gender: Female Factory Work in Germany, 1850-1914 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), p. 35. |

| ↑19 | In this way too, the figure and reality of slavery was absolutely crucial for the construction of ideas about what “free” waged work should be, especially as unions and socialists drew insistently upon the example of Black slaves to try and sort out what separated “wage slavery” in the factory from plantation regimes of racialized terror. For instance, consider this passage from “Yorkshire Slavery,” published in the Leeds Mercury, October 16, 1830: “Thousands of our fellow creatures and fellow subjects[…] are this very moment existing in a state of slavery, more horrid than are the victims of that hellish system “colonial slavery.” […] Poor infants! ye are indeed sacrificed at the shrine of avarice, without even the solace of the negro slave. […] Ye live in the boasted land of freedom, and feel and mourn that ye are slaves, and slaves without the only comfort that the negro has. He knows it is his sordid, mercenary master’s interest that he should live, be strong and healthy.” I address this history of comparison more at length in a forthcoming e-book, titled The Grid Aflame (from ICA Miami, later this year), which deals with analogy, infrastructure, and colonial networks. |

| ↑20 | Lucy Larcom, A New England Girlhood, Outlined from Memory (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1889), p. 226. |

| ↑21 | George Crabtree, quoted in Robert Gray, “The languages of factory reform in Britain, c.1830-1860,” in The Historical Meanings of Work, ed. Patrick Joyce (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), p. 148. |

| ↑22 | Mrs. Ephrain Holt, on women working in textile factories in Petersborough, NH, 1820s, in David A. Zonderman, Aspirations and Anxieties: New England Workers and the Mechanized Factory System, 1815-1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 21. |

| ↑23 | From Jeffries’ Land: A History of Swindon, published posthumously in 1896 (Jeffries died in 1887) and written in 1867 (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co, Ltd.), pp. 67-68. |

| ↑24 | Zonderman, Aspirations and Anxieties, p. 24. |

| ↑25 | Quoted in Helen L. Sumner, History of Women in Industry in the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910), p. 111. |

| ↑26 | Vilém Flusser, Gestures (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), p. 2. |

| ↑27 | Catherine Perlès, Les Industries Lithiques Taillées de Franchthi, Argolide: Presentation Generate et Industries Paleolithiques (Terre Haute: Indiana University Press, 1987), p. 23. |

| ↑28 | André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, trans. Anna Bostock Berger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), p. xviii. |

| ↑29 | Ibid, p. 246. |

| ↑30 | Ibid, p. 246. |

| ↑31 | Ibid, p. 313. |

| ↑32 | “The Idyll of Work.” Available online through the University of Michigan library at: http://library.uml.edu/clh/all/lu01.htm |

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine