“Where is the Sanders campaign getting this idea that he can win Michigan?” Vox’s Matthew Yglesias posed this question last week in a now-infamous tweet, before the upset victory of Bernie Sanders in Michigan’s Democratic Primary on Tuesday. Polls showed that he won with heavy support from members of the United Auto Workers, not to mention the overlapping enthusiasm of the historically politically engaged Muslim community. Widely deemed impossible by pollsters in the fevered coverage preceding the primary, this result breaks the media blackout on the outspoken “democratic socialist” candidate, as well as on an older idea: socialism. Since the days when the abstraction of countercultural “liberation” displaced the material project of “socialism” for the vast majority of the New Left across racial lines in the 1960s and 70s, interest in anything resembling non-capitalist solutions has been sharply limited. We would have to go back to the 1930s and the almost 900,000 votes for Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas, “Mr. Socialism,” in 1932 to find an equally popular socialistic figure.

But let’s dig a little deeper. The first consideration about Left history in the United States should begin with the context ignored by historians until very recent generations: for most of that history, a majority or large minority of activists and activities did not employ English as a first language. Think for a moment about the implications. Participation in elections had not been ruled out, but existed at a definitive disadvantage, long before the current era of seeming apathy. No wonder the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), responding to the socialist plea, ”Strike at the Ballot Box!” offered the humorous response, “Strike at the Ballot Box with an axe!” They had concluded that if socialist agitation in electoral politics may be a necessary educational effort, voting does not bring real change.

They had a point, those Wobblies, and momentum for their own movement—for a while. The vision of a strictly functional government, minus politicians, ruled from below by industrial councils, appealed to a desire to break the power of Washington, D.C. It also reflected the determination to encompass all working people, not just the (white, male, and privileged) craft workers of the American Federation of Labor, in the struggle from below. Wobbly theorists, most of them trained by Daniel DeLeon, the Caribbean-born sectarian leader of the small Socialist Labor Party, worked out a vision in which every mass strike hinted at the creation of a new society within the shell of the old, bringing the full and true working class into existence as a class for itself. By no surprise, the IWW faced overwhelming opposition from the AFL and massive repression during the First World War.

There is a real history to support their view. After the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, dozens of socialists were elected to local and state office, especially, but not only, in Illinois. By the next elections, Democrats had moved leftward and swept up the labor vote. In 1912, Democrats and Republicans at the local level formed joint tickets to defeat hundreds of socialists elected at various levels, and swamped socialists with redbaiting tactics not so different from those that are emerging today. No wonder that so many German immigrants of the 1880s—and, later, Italians, Slavs, Hungarians, Finns, and other communities where a kind of anarcho-syndicalism had great support—expressed indifference to political campaigns, turning all energies toward unionism, the building of social-cultural institutions, support of radical newspapers, and so on.

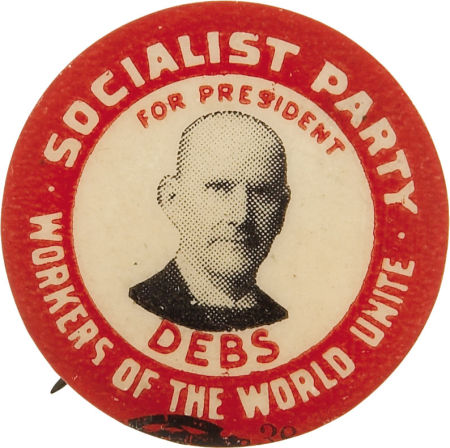

The difficult result of this overwhelmingly negative view has been the eagerness of many socialists, communists, and others toward the educational effort in the election process, and the expectation (or hope) that pressure can be exerted even when leftwing candidates are not elected. The aura of hope exerted by the personality of Eugene Debs still reverberated, among people in their eighties and nineties, when I interviewed them about their lives, around 1977-82. Debs offered a vision of what a cooperative society could be like, and his nationwide campaigns on the “Red Special” train electrified working class to lower middle class crowds, industrial workers to school teachers, everywhere he went. The effort to organize the unorganized was boosted enormously by his campaigns.

Perhaps there was never another such figure, and never could be, because the First World War ruined the optimism, the certainty of a socialist future, after that bygone age. Eugene Victor Debs, the former railroad union leader from Terra Haute, Indiana (named by his parents for French literary radicals Eugene Sue and Victor Hugo), had led the all-inclusive American Railway Union into the historic strike of 1894, and then into crushing defeat. He converted to socialism while in a jail cell. He represented the collective hopes of several generations, women quite as much as men, and for the first time in the socialist movement, thousands of African Americans, gathered mostly in Christian Socialist groups, but also in the burgeoning black community of Harlem. Imprisoned for calling upon Americans to resist the draft, he took nearly a million votes in 1920—behind bars.

But socialists behind Debs, running in local elections, galvanized something similar, or at least a sense of social solidarity. Although this memory seems almost vanished by now, they continued to do so in pockets of American society into the 1960s. What did they “deliver” in office? Genuine honesty for one, a rare thing in itself. But also city-owned utilities, where they could persuade city councils, better parks for working class leisure, good public transportation, and in some cities like Milwaukee, next to lakes, a ban on tall buildings that might block the enjoyment of ordinary citizens. Beyond the local, their opposition to most US foreign policy was no small matter.

If this seems like ancient history now, in the shadow of the Clintonian Third Way, think about this: there are now tens of thousands—over the course of the nomination campaign, hundreds of thousands—of people, disproportionately young, in motion, currently thinking about this strange idea called “socialism.”

Could it come at a better moment when, as John Nichols and Robert McChesney have explained in their new book People Get Ready, the era of upward mobility is over and disillusionment with capitalism at large is at a level unknown since the 1960s? Have we figured out how to transform these energies into an organized political form autonomous from the Democratic Party? No. But this is surely our opportunity to learn.

“We shall know more of what men want and what they live by if we begin from what they do,” wrote C.L.R. James in Beyond a Boundary. It was a thought he shared with me in many different iterations, as he observed movements of the 1940s-70s: watch what people are doing, stop theorizing for a moment to fit things into some preconceived formulation and…try to learn from them. The “Old Left,” Communist to Trotskyist to Socialist, could never grasp, at least until 1960s and often not at all, that the black movement had its own logic, its own moment, and its own language. Nor could they grapple conceptually with the culture (or counterculture) of the New Left, nor with the women’s liberation movement and so on. After all, small parties do not build movements.

We do not know the trajectory of the Bernie Sanders campaign, nor its longer-range implications. A skillful organizer with decades of work behind him in heavily blue-collar Rhode Island, a steelworker, human rights leader, and later radical preacher in multiracial communities, recently put the matter to me this way: “Think of Occupy, Black Lives Matter and the Bernie Sanders Campaign as waves, all of them leading to the next wave.” That’s a fine insight. Instead of measuring one against another, we would do better to see their connections and possible relations. In order to unite people belonging to different movements into a longterm, organized radical force in this country, we would do well to begin, as C.L.R. James advised, with what they do.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine