In this interview, conducted in Padua, Italy over the course of April-May 2019, veteran activist and militant theorist Ferruccio Gambino surveys fifty years of struggle on the Italian left. An introduction to Gambino’s work can be found here.

Dylan Davis: Who were some of your mentors, or the people who influenced you most, in your early political and intellectual development?

Ferruccio Gambino: I was born in 1941 to a family of small vineyard farmers in a village in Piedmont (Northwest Italy). My parents tried to protect my sister and me from the war and from its consequences, but the postwar hardships were everywhere for us to see. My early years at school were boring so I took refuge in reading the few books and newspapers that were available to me.

In 1955 I was admitted to the two preparatory years of Liceo1 in Asti. The Liceo bureaucracy in deferential Asti used to assign the sons and daughters of the city professionals to Course A, where teachers were rather conservative. Course B was mostly for students who came from the outskirts of the city, or the countryside, children of low-ranking bureaucrats, shopkeepers, workers, farmers, like myself. We in B got the left-leaning teachers, which was a stroke of luck, at least to me. Elda Jona was assigned to teach Course B. She was my unforgettable teacher in Italian, Latin, and Greek in my first year. She was Jewish and had narrowly avoided capture by the Nazi SS in 1943, while her sister Enrica Jona was deported to Auschwitz and was one of the few Italian survivors who returned to Italy, like her friend, the writer Primo Levi.

Among the teachings I received from Elda Jona I should at least mention that I learned how to coexist with my rising doubts about the Catholic belief in mankind’s ultimate salvation. Texts that we read in our classroom made it clear that human salvation was far from certain. As many teenagers have always done, I gave some thought to our probable cosmic loneliness and its consequent dilemma: should we lean on individualistic acceptance of the world as it is, in short quietism, or should we be for collective action in the absence of a savior? The books I borrowed from the Liceo library helped me feel that the materialists’ call to human action was much more widespread than I had imagined.

In the final three years of the Liceo my teacher in philosophy was Eraldo Arnaud, the Italian translator of Georg Lukács and Ernst Cassirer. Armando Fellin taught Latin and Greek, and in those years was translating Lucretius with materialistic passion, a work he published in 1963, just before dying prematurely. Both Arnaud and Fellin had been partisans. Although they never hinted at their participation in the Resistance to us, we knew about their exploits from former underground fighters in Asti. In short, I was in good hands during these crucial five formative years.

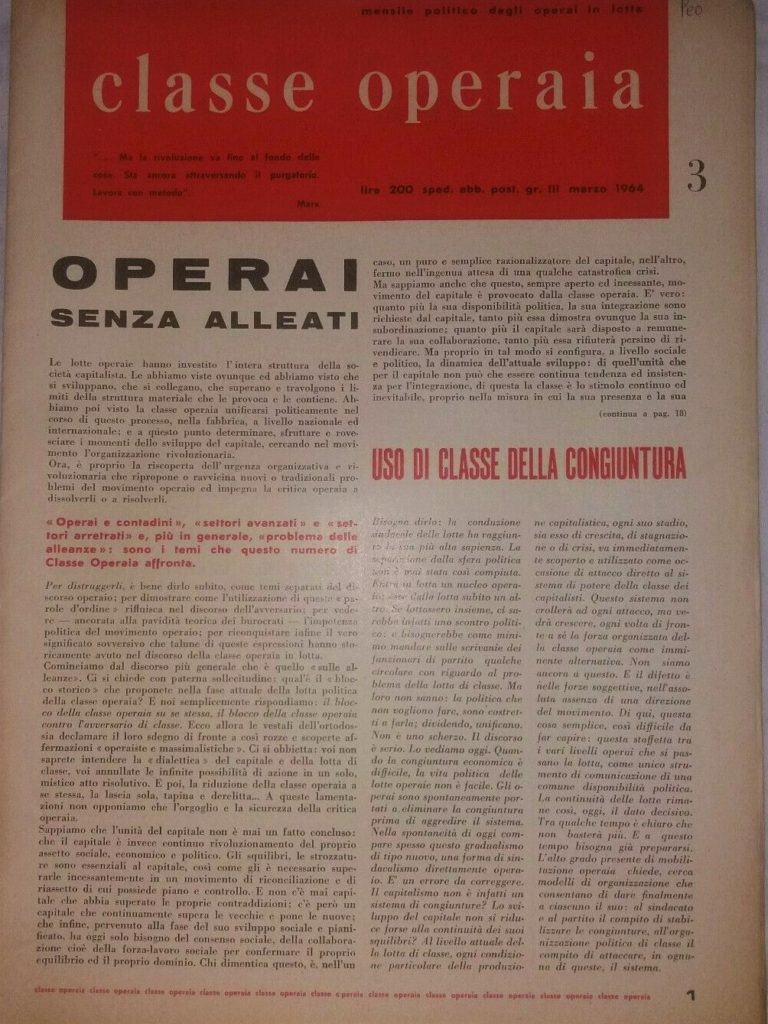

At the Liceo there were only three of us, all boys, who congregated near the church cathedral to discuss politics. That small group was my safety net, because Asti was a provincial city and not much happened there in those days. However, to Asti’s credit, the left formed an active minority. I could not pay any attention to it, because I was a daily commuter, forever pressed for time; I had to spend three hours a day of walking and trains. After the five years at Liceo, and at long last finding myself in a big city like Milan (since August of 1960), I was in the crucible of the Student House in Viale Romagna, or 550 young men from all over Italy and other countries crammed into one big building. While in Milan, and through one of my two friends in Asti, I heard about Quaderni Rossi in 1962, and later about the coming split into Classe Operaia. In early 1965 I began reading Marx’s Capital, and since then the world was no longer the same to me.

After graduation (July 1966) I received a Fulbright grant and got a job as an instructor in Italian at Columbia University in New York for a year (September 1966). I devoted a lot of time to reading at the Columbia libraries on U.S. history and sociology. I spent some long evenings with Murray Bookchin and young people around him discussing ecology and destructiveness at his apartment in the Lower East Side in the winter and spring of 1966-67. At that time Bookchin was in his anti-Marxist stage, but his animosity toward Marx and even more toward Marxists did not bother me. I owe him much for introducing me to ecology. I went to Detroit in late December 1966 and met the people in the Facing Reality group there. I participated in the April 1967 March against the Vietnam War in New York, and toured the United States (Detroit included) on buses for some 40 days in August and early September, before returning to Italy.

I must say that in the early months after I returned to Milan from the United States, Sergio Bologna’s help was indispensable to me. He was not yet thirty and already a well-known historian of contemporary Germany, of the working-class movement in the 20th century, and had gone through the experience of Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia. I had sensed that he had already a critical perspective about the Bolshevik tradition when I first met him in 1965. The same was true of Giairo Daghini, then an assistant to the chair of theoretical philosophy at the Università Statale in Milan. I met him in the fall of 1967. Giairo helped me to make ends meet with my translations and book reviews in late 1967 and early 1968, as he also knew the publishing world in Milan. He was knowledgeable about the Eastern world and understood the limits of actually existing socialism.

At that time few of the people from former Classe Operaia followed the news of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Most of us did not know much about it. When asked, we used to say that we wished the best for the Chinese people. But it was next to impossible for us to hold a down-to-earth debate on pressing Italian issues with the two tiny pro-Chinese parties in Italy, because we were neither prepared to idolize Chairman Mao nor to sloganeer accordingly, as they did at every meeting. I thought at that time that these people should have been an embarrassment to the Chinese representatives abroad.

In Padova in October 1967 I met Antonio Negri, Guido Bianchini, and the other comrades in Potere Operaio Veneto-Emiliano. I also met Manfredo Massironi, a visual artist and teacher whose design and graphics of Classe Operaia had impressed me as an innovative approach to the printed word of the left. The peculiar pale red color that he had selected for its headpiece and highlights harkened back to the pale red of the early farm workers’ and sharecroppers’ union flags and other symbols in 19th century Italy. When we first met, he was pleased to find out that I had got that message linking us to the origins of the working-class movement.

US Travels and Circuits of Internationalism

DD: You have described your early visits to Detroit as formative ones, and it was there that you established enduring friendships with Martin Glaberman and George Rawick, who were major influences on your subsequent work. Rawick was among many, including James and Grace Lee Boggs, Dan Georgakas, and John Watson of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, to visit Italy at that time. How were these visits conceived and received at the time? In what sense were you a kind of cross-Atlantic mediator between these milieus?

FG: As I said, I visited Detroit in late December 1966 for the first time. There I met the Facing Reality group whose leader – C.L.R. James – had been in exile since 1953, when he had been deported from the U.S. to England as a subversive Marxist. At that time he was in Canada and I could not meet him. I met Marty and Jessie Glaberman, Seymour Faber, Nettie Kravitz, William Gorman, George Rawick and other members in the group. The Facing Reality group in Detroit published a bulletin, Speak Out. We spent a lot of time in discussions at the Glabermans’ house. I did not know much about the history of the working class in the U.S. – from slavery through the 1950s – and George Rawick was careful enough not to inundate me with his immense knowledge of U.S. history. He used to suggest, correct, and hint at questions with great patience and interest. In August 1967 I received the promise that George Rawick and others would come to Europe soon.

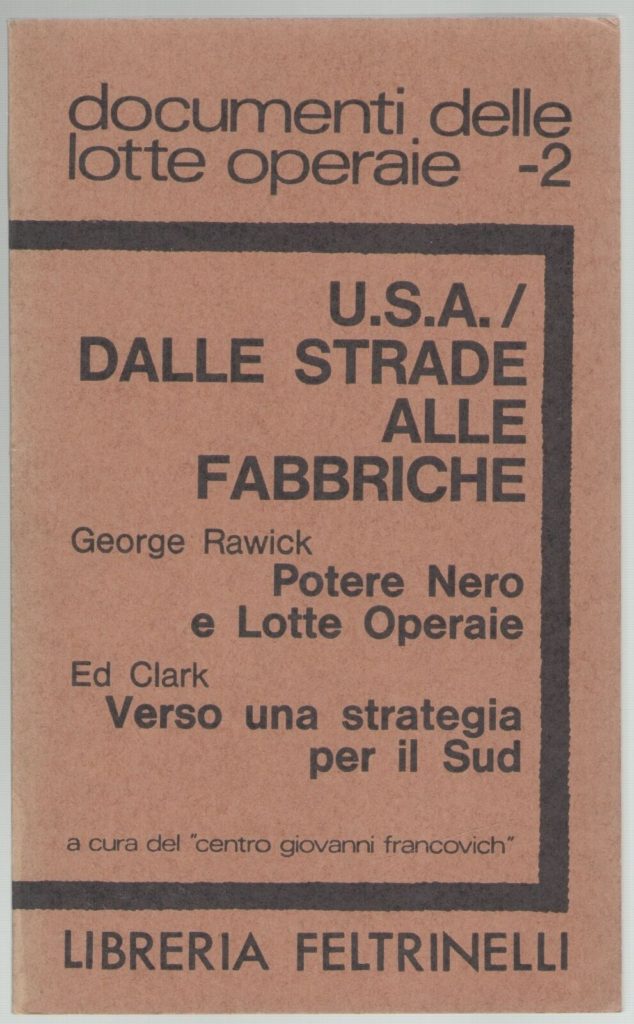

Rawick came to Università of Trento and to Università Statale of Milan in late November and early December 1967, during a break from his intense work in London on the early outline of his book on American slavery, From Sundown to Sunup. He gave a major speech on the desegregation movement in Milan with some 800 young people attending, most of them students. Later he gave a speech in Florence.

Visits to Italy by other advocates of revolutionary Detroit were organized by various groups. In the case of James (Jimmy) Boggs and Grace Lee Boggs, it was the Centro Frantz Fanon and the Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity (PSIUP) that organized their visit. That is when I met Giovanni Pirelli, whom I had not known before. I was just the replacement interpreter of Grace Lee Boggs and James Boggs in Milan. Their interpreter in Milan had given up, because she did not understand James Boggs with his strong Alabama accent. In other cities too interpreters could translate for Grace, but had a hard time with Jimmy. Dan Georgakas was in Italy in 1969 or 1970. He had been in Italy earlier on, and contributed to the journal Quaderni piacentini with his well-known “Lettere dall’America.” John Watson of the League of Black Revolutionary Workers came to Italy on two occasions. One was with PSIUP at their second national conference in Naples (December 1968). The second one was in 1970, when he came to Florence. I translated for him there. In September 1971 I met him again with two other comrades in the League who impressed me, Ken Cockrel and Mike Hamlin.

At the meeting in Florence in 1970 with John Watson, a group of German comrades from the extraparliamentary left was also present. There were moments when Watson just could not reach them. They could not understand what this “color-line” was about. “Why can’t the color-line be broken? Can’t you bring more class consciousness into this friction between whites and blacks?” were two of their many questions. I was just alarmed, as John looked at me and said “Now, we can split!” I said, “Hold on, John, let me have a few words with them,” and finally that meeting was set and we avoided disaster. But it was really difficult. Meetings like the one in Florence with militants who didn’t know much, or anything, about the situation in the U.S. or its history, proved really hard. It was no easy task to have them get some understanding of that “color-line” and how much it mattered.

Grace Lee Boggs was a very perceptive person. She understood quite well that it was not easy for an Italian audience to grasp the complexity of the United States. Probably offering much more than what she would have done in the United States, she really tried to convey not only events but a perspective of U.S. culture. Jimmy Boggs was a very warm person, one of the warmest people I have ever met. At some point, they even asked him about China. Now, it was probably the most pro-Maoist period in Jimmy’s life, and I must say that even then he was not very pro-Maoist. But he submitted an example that drew the applause of the audience. He said that at some point in China you may have to build a furnace in the courtyard in the process of ameliorating the Chinese working conditions, and it was almost as if Jimmy had been in that courtyard. Also, he had a profound understanding, which came to me as a surprise, of Martin Luther King. After being polemical with Martin Luther King for a long time, he said that MLK had been able to give coordination and discipline to a movement that might have gone anywhere; in short, we had to understand and appreciate his gigantic work. Although his admiration for Malcolm X was infinite, he knew also that there was another side to the story. James Boggs was right there; that’s somebody you call a fine political mind.

U.S. society had always been a challenging issue for Europeans, and for European leftists in particular. One had to remind European audiences of the fact that U.S. history is not just contemporary history. It had begun early in the seventeenth centuries for the Europeans and Africans, but much earlier for the First Nations. Probably another big tool was just repeating that, as in any conflictual situation, sometimes ordinary people’s struggles are visible and sometimes they are invisible, but even when one doesn’t see conflicts, conflicts go on. Surprise prevails among observers when a strike or riot or a revolt or an insurrection takes place. But conflict, no matter how deeply underground, goes on all of the time. Continuity, no matter how imperceptible, was George Rawick’s crucial point. And little by little, by insisting in those terms, it dawned upon people in Europe, mostly young people, that the struggles for desegregation in the 1960s in the U.S. were not improvised.

Young people in Italy took notes during those meetings; they read more, and they listened to more music than their parents. They soon understood that some link somewhere connected rock ‘n’ roll to black music. We had to insist that the United States was a subcontinent, not on the scale of a European country. We used to say “it’s like putting together Rostov on Don with Lisbon. You try it!” There was also a section of the young working class that had come back to Italy after migrating to other European countries, Latin America and Australia. The former migrants knew better, because they had been exposed to tense situations and discrimination abroad.

Like others, I was an interpreter for comrades visiting from abroad – and particularly for African-American visitors - with this sense that Italy was also the country that had begun its invasions in Africa in 1879, that had invaded Ethiopia in 1935 and committed war crimes there, backed by the approval of hysterical crowds in Italian cities, while those who didn’t approve had to keep quiet, unless they were ready to be beaten up on the spot or go to jail or both. It was the country that persecuted dissidents – mostly leftists – since the unification of the country (1861), as it had heretics, misbelievers and homosexuals for centuries, that passed anti-semitic laws in 1938, that joined the Nazi war in 1940. A rump fascist government in central and northern Italy was in cahoots with the Nazis in 1943-45. Together they set up concentration camps and even a crematorium in Trieste, the only crematorium south of Hitler’s Germany.

Most of these crimes came to be known to a vast public only in the ‘60s. But by the late 1950s an acting minority on the left understood the magnitude of this horror. However, the minute that one said in public that Italy since 1945 had closed both eyes on more than a thousand war criminals, one would risk being vilified as a rabid hothead. It became public discourse only in the 1960s, thanks to the relentless campaigns of the Italian left in opposition to the ruling government and conservative or outright reactionary media. As we grew up, I was just one of the many people in my generation who said “Never again.”

DD: You recently gave a talk in Brescia on the topic of Malcolm X, and have written on him in the past, including your piece,“The Transgression of a Laborer: Malcolm X in the Wilderness of America.” Can you speak about what initially interested you about him? What, in your view, might we learn from him today in the context of contemporary anti-racist struggles?

FG: My interest in Malcolm X began in 1964. At that time a teacher from the U.S. happened to say in passing: “There are racists, and then there are the racists in reverse.” So I raised my hand and asked: “What is a racist in reverse?” Well, he said, “you know, people like Malcolm X,” and he went on to explain his fears. I said to myself, that racism in reverse might be very interesting; it may mean no longer any deference to a boss.

Of course, when I was in New York in 1966-67, I read Malcolm X’s Autobiography. It was compelling to me, and I saw also that there was a lot of interest in his personality and his message. I leaned on Roberto Giammanco’s work on Malcolm X in the late 1960s in Italy. He had known Malcolm X personally, and translated his Autobiography into Italian brilliantly. Publications on Malcolm X in the 1970s in English and other languages (French, German, Italian) left me somewhat disappointed because they neglected telling his story as a precarious worker for fifteen years of his 39 year-long life. The FBI had constantly classified him as a laborer, before he became a full-time preacher for the Nation of Islam at the age of thirty (1955). I was trying to trace his working trajectory as a laborer since he was a teenager, and then an inmate. In the winter of 1981-82, while I was in the United States, I wrote an article on Malcolm X, “The Transgression of a Laborer” (later published in a 1993 issue of Radical History Review), in spite of the fact that the Massachusetts Department of Corrections denied me access to its documents, though it gave access to others.

That article left aside another topic in Malcolm X’s early preaching, his black nationalism and the issue of land, not a minor matter for African-American people who have been deprived of the land that they have cultivated for some 300 years. Land is an issue that seems to be out of fashion, but, I guess, not forever. The polemical tone against black nationalism (which has little to do with mainstream nationalism) has been harsh since the 1930s. There has been little understanding of the scope and consequences of the deprivation of land. Another aspect of Malcolm X’s world vision, his internationalism, has hardly been understood. It is part of a larger picture of proletarian internationalism, which he began understanding in the course of his expanding world vision beginning in 1957. In 1959 Malcolm X went abroad for the first time in his life. He traveled to Egypt and Saudi Arabia to meet dignitaries and rulers there. Six years later, in February 1965, he took his last flight, went to England, participated in a debate in Oxford, and then visited the working-class town of Smethwick, near Birmingham, where he denounced the ethnic and religious discrimination against West Indian and South Asian immigrants. No more dignitaries and rulers.

I don’t think that there can be any future internationalism without a deeper understanding of modern forced and voluntary migrations. If there is to be any significant working-class political movement in the future, I think that we should pick up where Malcolm was at, and redress the consequences of all forms of bondage, an issue that previous experiences of left internationalism was inclined to take lightly or neglect. In particular, modern slavery and servitude have structured both voluntary migrations and the abysmal class divisions persisting in our contemporary world. Those who – like the Republicans in the post-Civil War United States or the Bolsheviks in late czarist Russia – ignored or underestimated the depth of those class divisions, did fail.

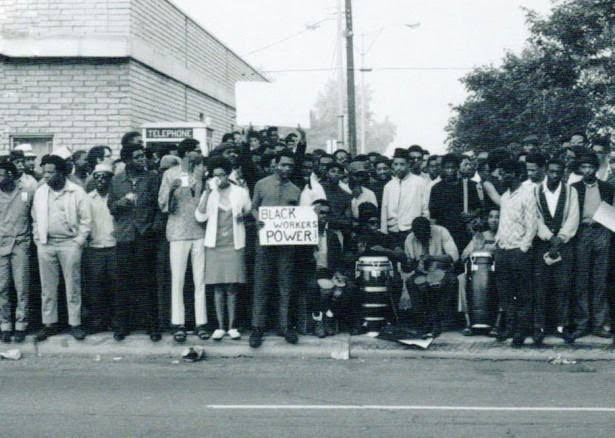

DD: How did W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction influence you? The workerists developed an important political reading of Black Power in the US – how was that movement viewed as an expression of political recomposition and working-class autonomy?

FG: I read Black Reconstruction for the first time in 1967. The book impressed me for two main reasons: First, because the history of Black Reconstruction demonstrated that the attack on the working class in the early period of large-scale industry was expanding worldwide. In the United States, as well as in other countries, it had the colossal peculiarity that it was linked to crass racist discrimination. Similar processes were going on in Africa, Asia, Europe, and in Tsarist Russia. Those who were considered non-white were bound to agriculture, some mining, menial and ancillary jobs. Black Reconstruction was a reflection on a case, the U.S. South, part of a wider process, usually called large-scale industrialization in the second half of the 19th century and in the early 20th century. Racial discrimination assisted large-scale industry, even more than it had assisted manufacture. To me Black Reconstruction revealed also the social fragmentation of its exploited and oppressed opposers after the end of the U.S. Civil War, and of the Paris Commune. The working-class response in the late 19th century was fragile. It was split along color lines, it was often geographically confined, it relied on capitalist development and technology, notwithstanding genuine socialist internationalists and feminists who were trying to open universal perspectives. Du Bois published Black Reconstruction in 1935, a disastrous year for exploited people globally. Yet in Black Reconstruction Du Bois proved that ordinary people who had been slaves could not be easily repressed.

We, the “workerists,” developed a peculiar reading of Black Power in the U.S in the late 1960s. There were two main different views of Black Power in Western Europe: one was more working class-oriented and looked at what was happening that suggested a renewal for the Left. The novelty for Potere Operaio (PO) and Lotta Continua, as well as other groups, was revolutionary Detroit, particularly before and after the ‘67 Detroit revolt. Others, such as Collettivo Politico Metropolitano in Milan tried to imitate the style of the Black Panthers, and even wanted to borrow their language. It was no big surprise that they later became a component of the Red Brigades. In brief, there were contrasting views. And a large part of the Italian extraparliamentary movement at that time was not much impressed by the Black Panther Party, and particularly by its alliance with the Communist Party USA.

In the mid-1960s Soviet books such as One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962) by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and by other opponents to the Stalinist regimes had already been translated into Western European languages. It was largely evident that the situation in the Soviet gulags and other concentration systems was much more serious and extensive than ordinary people had known in the late ‘50s. Also, opposition to the war in Vietnam did not require loyalty to any communist party. Marty Glaberman of Facing Reality in Detroit articulated this position for many younger leftists when he used to say that “we don’t have to adhere to Ho Chi Minh’s line to tell people that the U.S. military intervention is a rotten war.” There was a spectrum of positions in the extraparliamentary left that ranged from reservation to outright opposition to the Communist bloc. For instance, Malcolm X never visited Cuba. At a meeting in Paris in November 1964, Malcolm X is said to have claimed: “I know that not even in Cuba have the whites let the black man get to the top.”2 That he had renounced visiting Cuba impressed me. The people who were describing Cuba as a country suspended between fear of a U.S invasion and social harmony had perplexed many of us, although our sympathy went to a country facing the largest imperialist power in the world at close range.

In 1968 in London I again met George Rawick who introduced me to Selma James. C.L.R. James was still in North America at that time. I met him for the first time in 1969 in London. In reading his works I discovered that his line had been quite consistent since the 1930s, when it already diverged from the Stalinist course. He recounted the episode of his childhood friend George Padmore’s return to London from Moscow in 1933. Padmore knocked at C.L.R. James’s door and said that Stalin’s Third International had abandoned anticolonialism in Africa. Moscow was aligning itself with the colonial powers. Anticolonialist militants had to start all over again from scratch. C.L.R. James had not believed in the Stalin myth. Consequently, he and a few comrades in England were prepared to do whatever they could against colonialism regardless of Moscow’s policy. It was a crucial lesson for later generations, including mine. In the 1950s and even more in the 1960s there was a critical mass of leftist activists in the West involved in anticolonial campaigns, acting independently from the communist parties.

DD: On the other hand in the late 1950s and early 1960s there were broad sympathies for anticolonial struggle among Italians, with the Italian Communist Party (PCI) even devoting resources to diffusing texts by Algerian militants, a development obviously in contrast with the French Communist Party. Figures like Frantz Fanon, for instance, were very popular in Italy, whereas his works were censored in France. What did you make of this at the time?

FG: Activists for the Algerian independence abounded in Italy as in other Western European countries. In West Germany, for instance, a group of leftist militants organized an underground network of Kofferträger, or “porters of suitcases,” for the pro-Algerian clandestine centers in Europe and in the Maghreb. Sympathizers were a composite group of people and entities in Italy. The Communist Party and the Socialist Party were definitely for the National Liberation Front (FLN), and their press followed the news of the Algerian war closely. The Italian state-owned oil company Eni helped the FLN with money and weapons. The hub of the Italian support to FLN was Milan. It was there that former partisan and writer Giovanni Pirelli had founded with others the Centro Frantz Fanon and promoted Fanon’s books and many initiatives in favor of Algerian independence and of anticolonial struggles in Africa and later Vietnam. Even at the Casa dello Studente in Milan we organized debates with Algerian students, which were very well attended. There was a lot of sympathy in Italy for the Algerian fighters, and for the demise of colonial empires. At that time Milan was a point of transit for refugees coming from Africa, Asia, and the Eastern European countries, particularly from Poland. They usually did not stay for long in Italy; they tended to try and go to richer places, such as the Scandinavian countries, or the U.K. or Canada and Australia. There were also students from Iran and Iraq who were telling their stories about the harsh working conditions in the oilfields. In short, progress was not so rosy.

That international dimension, I think, was very important in the maturing not only of the group that later joined Potere Operaio and other extraparliamentary groups but for a lot of young people who were forming their own opinions about the real power relations in world politics. Also, that anticolonial worldview was connected to the Italian Resistance. Former participants in the Resistance understood anticolonial struggles, and supported them in the 1950s. Then, in the late 1950s the British and French decided to decolonize in Africa. Apparently it was a break from the U.K.’s war and concentration camps in Kenya and France’s war and concentration camps in Algeria. By formally decolonizing in Africa both governments were able to focus on their vital investments there, while leaving their former “colonial subjects” to their own destiny. As an early example of the treatment that France reserved to the countries that did not accept neocolonialism, we got the news in Milan of the plight of Guinea, thanks to a Guinean engineer who spent a year at the Milan Polytechnic. Guinea had rejected French President Charles De Gaulle’s offer in 1958 to join the “Communauté française,” a French-led umbrella association of its former colonies. The French armed forces retaliated against Guinea by destroying Guinea’s infrastructures before they left for good, a story that was largely ignored in the European press at that time.

There was both a sense of the real world, so to speak, in booming Milan, for people who wanted to understand, and clear evidence of the real relations of power, even in the visual dimension of the city. In the squalor of the outskirts of Milan, as early as 1962, three years before the official U.S. intervention in Vietnam, there was gigantic graffiti hailing “Viva i Viet Minh” on many walls. Those writers did not know that the fighters were no longer the Viet Minh of the Dien Bien Phu victory (1954), that now they were the Viet Cong, but they wrote in very large lettering anyway. That graffiti stayed there for years and years, a monument to Milan’s internationalism.

Class Struggles in Italy and Potere Operaio

DD: Where were you in 1969? Why did the events of this year mark such a significant turning point?

FG: Throughout 1968 and 1969 I was commuting between Milan and Padova every week. By that time I was involved in getting in touch with people in Milan and trying to organize small groups there, both in factories and universities, and even conducting small group discussions on Marx’s Capital. Then I spent a little over one week in Turin in May 1969. I saw how the PO group in Turin was structuring itself while welcoming motivated young people from all walks of life. There was no question that the main personality there was Mario Dalmaviva. It was in the spring of 1969 that Mario invented a new way of relating to workers at the factory gates, when they were getting in or coming out. With simple tools: word of mouth, and leaflets. He could really discuss with any other group in Turin, as long as their leaflets had some sense. I have never seen Mario lose his temper, even in tense situations. He knew every nook and cranny in Turin. He had two main aims: One was that the direction, or orientation, of the conflict that was already boiling had to be expressed as clearly as possible, in terms of demands, in terms of organization, in terms of self-activity, within the plants. His second aim was that, while this ferment was rising, a group of really dedicated militants, had to be built up, and that these people did not necessarily have to be intellectuals. At the same time, he was never offensive to the trade unions, or the PCI, or the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), or to anybody. He was not personally hostile to anyone. The aim was really to get out of this mess, and this mess was how Italian industry, and Fiat in particular, was run, which was basically a horribly authoritarian entity in the largest company city in the world.

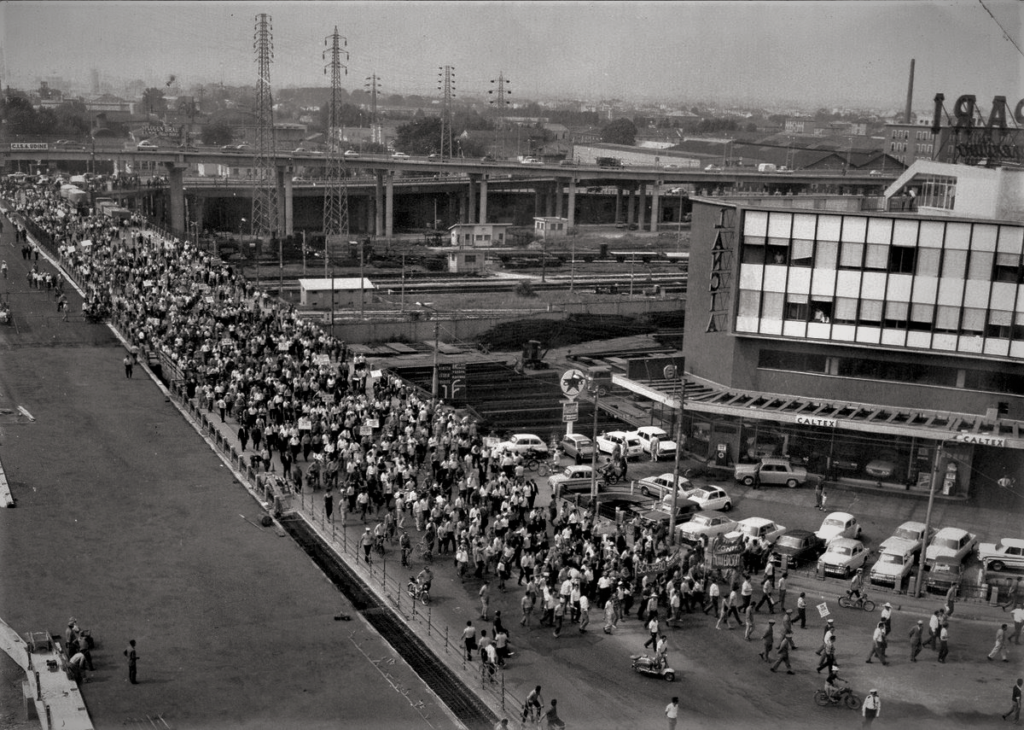

Mario could have been a billionaire, but had rejected a life in wealth. He had been a very important manager for antiques and art collections in Rome, dealing in luxury goods. In May 1968 he had suspended his activity at once, had gone to Paris, and by August he had quit his business, started a new life, enrolled in sociology at the Università of Trento, and put together a Turin group of student-militants. He was also able to organize debating groups among young people who understood the importance of the French and Italian events. A big turning point took place in early June 1969 when issue No. 5 of La Classe – a paper of “workers and students” – was distributed to the Fiat strikers in Turin, right on time at the factory gates. There is no question that the isolation the working class in that city had suffered for so many years was gone. The tragedy of 1962, with the Piazza Statuto revolt, was the fact that massive support was not available, apart from a few leaflets by the Quaderni Rossi people. The miracle of 1969? These workers no longer felt isolated. The support they experienced from young people made the difference. Once mobilization proves that it can be done, it becomes possible elsewhere too. And that is why the police on July 3, 1967, upon seeing a march that had been officially forbidden, and mistaking the marchers for students, attacked with tear gas and truncheons, not knowing that behind them were three thousand workers.

When we in Milan got the news of the dimension of this battle, that went on until the dawn of July 4th, we distributed a leaflet at factories and universities about the significance of the Turin revolt. On July 5th Le Monde published an editorial on the events. In the text of the article it was stated that it was “une journée de manifestations presque insurrectionnelles” [a day of nearly insurrectional demonstrations].3 In Italy the outcome was that in the parliamentary left the PSI split again, three or four days later. There was definitely a part of the political elite in Italy that said, “We are not going to allow this mess to continue for long,” a sentiment which was, as it turns out, at the root of the Piazza Fontana bombing and massacre [strage] on December 12, 1969. I remember that we were congregating in Milan, probably in September of 1969, and we were congregating at a rundown hotel just in Piazza Fontana, where there were meetings every evening, with activists from factories, universities, and schools. There was a strike at Pirelli that was going on and next to me were two workers from another factory. They turned to me and one of them said “Now, for the Pirelli workers the next few days are very hard because the strike is ending, and when the strike ends it is probable that some workers would be sacked.” The other worker turned to me and added: “I’m afraid of a strage.” Just two months later, in December, a bomb exploded, killing 13 people and injuring many others at a bank in that very same Piazza Fontana square.

Three days later, Giuseppe Pinelli, a leading anarchist, was dead after a fall into the courtyard at the police headquarters in Milan. Sergio Bologna and I were in Padua, and the first thing we said was “now, as he was a brakeman for the railroads, he must have passed some psychological testing, right? And it’s unlikely for a man who has undergone these tests to fall by himself that way out of a window.” Those who organized the explosion were in cahoots with those who accused the anarchists of the bombing. The pieces started to come together, like in a mosaic, although the official truth has never indicated the instigators of the bombing.

Protests against the Piazza Fontana bombing were subdued in 1970. There was a lot of uncertainty in the extraparliamentary left about who had planned the bombing. In 1971, PO, Lotta Continua, and Lotta Comunista (a left-communist group) decided that there would be a meeting in front of the Politecnico in Milan to protest the fact that no serious investigation had surfaced about the bombing. At that point the police were around all over downtown Milan. They found several young people in PO preparing Molotov bombs, but their arrests were really due to the fact that PO was isolated. Lotta Continua had announced early in the morning that they would not come to the demonstration. It was only later that people began to have the courage to challenge the official versions, as there were more than one, of what had happened at Piazza Fontana. For long months it was all fear and silence, except for a booklet that denounced the inconsistencies of police reports about the case. What authorities did in order to repress whatever rumors were spreading was incredible, and it’s only through so much hard work, publishing, and spreading the word around, that by the mid-1970s, at long last, some information surfaced on the responsibility of the extreme right with the connivance of the Italian secret state agencies. However, there are young people in Italy today who, in their history courses and elsewhere, happen to learn that the Piazza Fontana massacre has been committed by the Red Brigades!

DD: You have described Potere Operaio as a kind of incubator for the development of diverse political expressions, including what you call “a new wave of feminism” in Italy. What do you think was novel about this grouping, especially in the Veneto region, with all of its consequent tensions?

FG: First, the development of PO had more to do with a strain in the tradition of Italian socialism than with the PCI. While both the PCI and the PSI had considered industrialization as the only road out of the ruins of the war, they paid much more attention to the backwardness of the countryside than to the real condition of the working class. However in the 1950s the PSI was more open to a minority that intended to debate the heavy price that the working class was paying for the new Italian industrial development. Raniero Panzieri, the initiator and leader of Quaderni Rossi, was a prominent personality in the PSI who also knew the South – and Sicily in particular, where he had led land occupations of latifundia in 1950. Antonio Negri and Guido Bianchini came from the PSI. Moreover, when I began attending meetings in the Veneto region I noticed that the presence of women was larger than in northwestern Italy, and that most of them had been in or around the PSI.

Secondly, the idea of bringing together workers and students, though not an absolute novelty, involved only a very tiny minority of students up to 1968, nothing like the Italian scene in May or June of 1969. Was that transformation easy and spontaneous? As Marty Glaberman used to say: “spontaneity is others’ organization.” In fact, it was prepared over a long period, between 1962 and 1968 because the organizational network in Turin in 1962, with Quaderni Rossi and then Classe Operaia, and also with il Potere Operaio in Pisa, were evidence that it could be done, even though it was done on a small scale.

Third, the separation between parties and trade unions was crumbling down. The unions had been somewhat of a special field for people who were familiar with political work: a young activist could work within the Italian General Confederation of Labor (CGIL) no matter if one was in the PSI or PCI. One’s party was one’s tag, but in trade union activity party membership mattered a little less than in parliamentary politics. People with anarchist tendencies were accepted within the CGIL, tolerated within the PSI, although not within the PCI. In short, the CGIL was more comprehensive of the Italian political spectrum than the two left parties. For instance, in the CGIL, and particularly in the metal mechanics’ trade union branch (FIOM), the members of the FAI (the Federation of Italian Anarchists) and Lotta Comunista could be elected to become union representatives, although they were tiny minorities within CGIL.

Who were these “new” students? They did not belong to old dissident groups with few exceptions. Most of them shared at least two characteristics. One was that most of them lived quite far from their families, usually having moved from South to North or from North East to North West, or from the remote Northern countryside, like myself, to the big city. The other characteristic was that many of them were coming to the left after breaking away from the Catholic conservative tradition, which was very prevalent in the early 1950s. There were, of course, secularised universities in Italy too. The temple of secularization was the Università Statale of Milan, where I was a student. I must admit that Catholic students had a hard time there. I remember a professor of the history of philosophy who once called one of them “Lei dai capelli rossi” (you with red hair). He didn’t make an effort to call him by his family name. Of course we, the secularized ones, stayed away from the Catholic university in Milan, where students in the 1960s were still compelled to make a solemn oath of faith to the Catholic church before graduation. Later they abolished the oath. In the 1960s it was still a split society in that respect, to the point that the watershed was not an abstract alternative between being conservative or progressive. The watershed was one’s going or not going to Mass on Sundays, eating or not eating meat on Fridays, whom one was going to marry, and where – in a church or at the town hall.

Also students without support from affluent families were coming to the conclusion that they were not isolated in society and that they had to face problems of survival in a big city collectively, while their families could not really give them more than a minimum aid. All this trouble had some elements in common with the straitened circumstances of ordinary workers. The film Pelle Viva by Giuseppe Fina (1962) captured a strategy of minimal survival practiced by factory workers who had to commute between the countryside and the cities. And poor students too were living on an Existenzminimum, no matter how great their expectations were.

In August 1968 a motley group, myself included, tried to organize a Comitato operaio [workers’ committee] in the northern outskirts of Milan, near the big steelworking and rubberworks area. We could not find many students to come to the meeting. One year later it was a completely different story. A call at short notice during a student meeting could mobilize fifty, sixty, seventy people. Before spring 1969, if a dozen students were on a picket line it was some success. Still, in 1968 there was a critical mass of “intervention,” as it was called, that made the difference, that proved that the mobilization of students could be done; that it was minoritarian but not impossible.

As to the capacity of PO to mobilize people, the most numerous group was in the Veneto region, some fifty people in late 1968; there were some twenty people in Bologna, several in Modena, and Ferrara. The group in Milan was smaller, and had problems laying down roots in factories, and even at universities. By early May 1969, a group of some twenty people had formed around PO in Turin. It was an aggregation of students, mostly students in sociology in Trento (the only faculty of sociology in Italy at that time) and architecture in Turin. There were not more than 10 or 15 people in factories who sympathized with PO at that time. Of course, the personality of Mario Dalmaviva was important, crucial, as I’ve said. He had a feeling not only for the proper way to lead in front of the factories but also for supporting the maturing of younger students who were at high school. Genoa was a different story. One of the personalities in Quaderni Rossi and early Classe Operaia had been Gianfranco Faina, a historian. He had split from any Leninism in the early 1960s after working within the rigid PCI apparatus in Genoa. Leninism was alien to him and to the tiny group of people around him. PO in Genoa had to do without Faina, because Faina suspected some Leninism in PO. The PO people in Genoa exerted some influence in factories later on.

Florence was a different matter still. It was an old Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia place, through Claudio Greppi, Lapo Berti, and a very young intellectual, Giovanni Francovich who died in a car accident at the age of 24 in 1966, and who would have played a major role had he lived. There was also a strain of anarchist-libertarian tradition in the Florentine factories, which was personified by a noble comrade who was a worker at the Galileo factory, Luciano Arrighetti. He was born in 1920, the oldest member of PO nationwide, had circled around anarchism and libertarians, and was a union member of FIOM-CGIL. At one point he had joined the PSI. He had long been aware that something was rotten in the Soviet experiment, and did not want to have anything to do with it. When he heard of Classe Operaia and then PO, he joined. He exerted some real influence among workers at the Galileo Works, and also at other factories in Tuscany for decades. He was highly regarded as a “factory intellectual.” Friends at work used to make fun of him and say that “it’s not at every factory that ordinary workers show up at work with a copy of Le Monde or Le Monde Diplomatique in their pockets.” He kept an internationalist view of the working-class movement. At an international meeting of trade unions in 1966 or early 1967, he was the only one who called for a pan-European general strike against “the American war” in Vietnam.

These groups in northern and central Italy were able to organize with students and younger people. In Rome there were groups of students with little or nonexistent contacts with factories. Later, PO students found several factories outside of Rome where they had influence, but that influence mostly served as kind of an appendage for them. Basically PO in Rome was a student movement. In Naples there was not much before 1971-1972. Since around 1971 Mauro Gobbini and others went there, organizing around the steelworks and other workplaces on the outskirts of Naples. Elsewhere in the South there were individuals, around Bari, in Crotone in Calabria, people who got our leaflets and newspapers from the North, just contacts. Courageous militants from Rome PO helped to set up a group at the Gela (Sicily) oil refineries, while in Sardinia the extraparliamentary left, including PO, was active in new industrial areas.

Geographically it was a network. In the Emilia region three important groups should be mentioned. They were politically very close to the Marghera Comitato operaio: Bologna, Modena, and Ferrara. In 1966 in Bologna a few students, very young at that time, got in touch with PO

Veneto-Emiliano. Later some of them, including Franco Berardi, or Bifo, joined that group while Classe Operaia was folding up. The Bologna group grew and reached a critical mass that was large enough to have a real influence both at factories and at schools from late 1969 on. Paolo Pompei, Giuliana Picelli, and Marcello Pergola were active in Modena, where they established a few excellent contacts at the Fiat works. Giuliana Picelli also was one of the founders and authors of Lotta Femminista in the early 70s. In Ferrara the two senior activists were Guido Bianchini and Licia De Marco, with a following of many young students. The situation in Emilia-Romagna was composite, but I must say Franco Berardi’s presence was important in motivating the Bologna group.

In the early 1970s the spectrum of attitudes within PO to the feminist movement was as wide as those the feminist movement took vis-à-vis the extraparliamentary groups. It went from strong sympathy and mutual help to antipathy and estrangement. Personality, upbringing, as well as previous social and political experiences among the older militants suggested mutual respect and a “do not intrude” request in both camps. Among the younger feminists, however, there was a more pressing demand: “stay away.” Both camps knew that they were on their own, afar from the institutional left, and therefore that hostility should be banned. Although, regrettably, there was a failed attempt by young PO members to disrupt a meeting of Lotta Femminista in its early days in Rome.

DD: What was your role in the organization? How did it operate day to day?

FG: PO was at the same time an interventionist group and a training school. It organized training centers for people who not only wrote leaflets and distributed them but also debated a variety of issues. Discussions and debates took place inside and outside of PO proper. They permeated the students’ dorms and other venues in many cities. Younger people complained that we had too many meetings and the schedule was very grueling, but I must say – to Antonio Negri’s credit – that he also proved to us the importance of debating. On that issue he was tireless and absolutely right. He felt that the group was both a training school and a political group. If we did not get the opportunity to debate, many initiatives would just stop because of lack of motivation. In turn, without debates the people who wanted to speak and express themselves, to bring their proposals to the group, would have been frustrated. The “riunionite acuta,” or “acute meeting mania” (as it was quite often ironically called), meant that people had to move around during weekends. There was a national meeting every 15 days, in Florence or Milan, and to a lesser extent Rome. People had to come all the way from Naples or Trieste, for instance, or further. But meetings were almost a moral duty. Persons convened had to be present. There wouldn’t be any place where we were active that didn’t send at least one or two members to the national meetings.

At the beginning of PO I was part of a minority of maybe three or four people who wanted to get in touch with as many other groups as possible abroad. So it was mostly Lapo Berti, Sergio Bologna, myself and a few others who spoke several languages, who put together a group for the contacts abroad. I think that was a fruitful move, because we were able to get in touch with people in Germany, the Hamburg Proletarische Front, for instance, and the group around Cohn-Bendit in Frankfurt, and even collectives in France. At the end of the 1960s it was difficult to find really active groups in France. By 1970 the French extraparliamentary left was in pieces. However, we were able to get in touch with the right people. One of them was Yann Moulier Boutang, very young, but already a leader at that time. I met him for the first time when he had just finished his lycée and was not yet a university student. In England I was in contact with Selma James, C.L.R. James, and their group in London. They were in international contact with quite a number of people, particularly in the West Indian community in the U.K. and in the West Indies.

Our first aim in Europe at the time was to work with migrants. At the beginning it was just Italian migrants, people who had moved to Germany, England, Switzerland, France, and Belgium, but mostly Germany and Switzerland. Migration was not conceived of as any specialized, sectional, or worse, parochial field for intervening with Italian workers. On the contrary, our perspective was the new immigration from Spain and Portugal, from the Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa to France and from Turkey to Germany. There was a fraction of former soldiers from Africa who had been recruited by France and who had remained there after the colonial wars but mostly it was Maghreb workers who had migrated while their countries were obtaining their independence from France. By 1970, for instance, about half the workers in steel in France were migrants from the Maghreb. I insisted on the perspective that immigration was a rising trend, that it was growing in importance, and that we needed to begin our analysis from scratch, starting from the situation we knew best, which was of course with Italians abroad. The ambition was not only to reach Italians, but also other people, and that’s why we had several actions with activists in different countries.

Rethinking Migration, Imperialism, and Labor History

DD: Moulier Boutang has recollected in an interview that “the question of immigration interested our Italian comrades, especially those of Potere Operaio. Italian immigration was interesting as a mode of propagation, but it was not the theoretical problem of immigration as a fracture [spaccatura] within class composition, as a real problem of the latter. I remember that it was difficult to explain to our comrades at FIAT or to Romano Alquati that having 22 nationalities is not the same thing as having one Italian working class: even if there were Italians from the South, it was something different. And when 300 Tunisians were hired at FIAT in ‘73, I remember perfectly that I said to Alquati, to Toni [Negri], and to others that this phenomenon needed to be watched closely, because it was very important. That they did not was, I think, a great error[.]”4 How did you and other researcher-militants at Padua tackle the question of migration and the figure of the “multinational worker”?

FG: Yann is absolutely right on this point. It was not taken seriously within PO in Italy except for the few of us who did international work. PO in Italy believed that before migrants could arrive in Italy, the most recent Italian migrants in Europe would come back home. This hope was just wishful thinking, in part because those who wanted to come back had already done so, as industry was picking up in the 1960s, in part because there was no point trying to figure out who would come back to Italy in ten years time. Around 1977-78 it was already quite apparent that low-key immigration from Yugoslavia, the former Italian colonies in the Horn of Africa, and South Asia to Italy had started. After 1971-1972 Italian migration to other countries was slowing down, and the incoming flow was growing.

Now, Romano Alquati – who was never a member of PO but who sympathized with it – was not sensitive to the issue of migration. This attitude in Romano and others derived, I suppose, from their biographical distance from colonial situations. They probably didn’t see that the trend of migration from former colonial countries was a very serious and looming issue for the working class internationally, whatever “working class” meant at the time.

Difficulties and misunderstandings were not limited to Italy. I insisted that one could not speak about the American working class, but one could speak about the working class in the United States. We needed to stop using the adjective “American” for the U.S., because Mexicans and others get angry at it, and they are right to get angry. Don’t speak of the making of the English working class, although I admire E.P. Thompson’s work. The working class in England was not just the English working class between 1792 and the 1830s. It is the working class in Italy and not the Italian working class. At that time it was very difficult to explain what was at stake, not only difficult with Italian comrades. It was even difficult with George Rawick! I had to correct him all the time. And then he came here, I think in 1978, and finally referred to the “working class in the United States,” not the American working class. I thought at that time that my obsession had worked. In that respect I was on the same wavelength as the Sojourner Truth Organization in the U.S., a militant group that was courageously facing whiteness and racist prejudice, and one that I remained constantly in touch with, especially Noel Ignatiev, one of its leaders.

This attempt to move from the territoriality of the working class to its mobility, or its non-ossified location, was really a tough campaign in the 1970s. At the time, a mobile intervention that we organized was on trains bringing back Italian migrants who worked abroad in Europe. We printed leaflets for two or three years that went like pieces of soap. I remember there was a comrade from Vicenza who spent about 72 hours nonstop with others at the Verona railway station just before Christmas. He came back and reported: “you know, if we had had piles and piles of leaflets they would have still disappeared.” These were leaflets for migrant workers, attacking both the conditions they were going through and the government here in Italy. We basically covered every train arriving in Italy from Germany, Switzerland, and France in those three or four crucial days before Christmas. It was quite a lesson for everybody because the response was really incredible. Of course the authorities in the railways stations were very nervous about this mass distribution of leaflets but they could not do much because we were just distributing leaflets in overcrowded trains to exhausted long-distance travelers, nothing important there!

Around 1972 the situation in some cities abroad was getting more difficult than we had estimated because the Italian right wing was also trying to intervene on a nationalistic basis in Germany and elsewhere. The right wingers did not have much leverage in Switzerland because they basically had no tradition there, while the Italian migrant left had deep roots there. The Italian socialist and anarchist groups in Switzerland had been very strong since the late 19th century within the Italian immigration, which was constantly left-oriented. Traditionally people who were persecuted in Italy crossed into Switzerland, at least as a first step in their flight from aggression or incarceration, and Swiss solidarity with the persecuted had always been strong. However, in post-WWII Germany, when our comrades went to Volkswagen at Wolfsburg they had to deal with the so-called Comitati Tricolore which was an organization of neo-fascists trying to mobilize Italians as Italian nationals, against other migrants.

We also had contacts in Belgium. There were migrants who were interested in PO in Belgium, and they happened to work in mines right at the end of that coal-mining history. Mines were closing in earnest in the late 1960s. There were only a few pits still open there, particularly in the Limburg province. These were exhausted mines. It was heartbreaking, seeing fairly young people whose lives were still dependent on obsolete pits that were near exhaustion. Some of the miners kept themselves afloat by moving from coal mining towns to large Belgian cities. In short, those who quit the mines saved themselves.

At that time there was a blindspot among many militants in Italy on the issue of migrants in general. I for one had to push really hard in Marghera, where some of the activists and sympathizers understood, but others did not consider it much of a political issue. Their attitude derived in part from their daily treadmill. “We have enough problems here already.” My reply was a question: “why shouldn’t we think about what is going to happen in a while?” The blindspot was not just unique to people in PO. When Lapo Berti and I tried to introduce this kind of inquiry in public, it was as if we were dealing with a kind of luxury – an item that would be desirable in the future.

By late 1972, I must say, I was pretty much fed up with the conduct of PO in several cities in Italy, particularly in Rome. The space for debate was shrinking, little attention was paid to young people who joined PO, and even the rudiments of a political formation for new recruits were neglected. I kept the contacts that I had been able to develop over the years but at the same time I saw that PO had become a lost cause, as far as the international situation was concerned. It was not until PO was dissolved early in the spring of 1973 that a few people such as Mario Dalmaviva in Turin, Luciano Ferrari Bravo and myself in Padova tried to pick up some of the pieces.

Around 1975 Luciano edited a book on multinational companies with his long introduction, and several other articles (by James O’ Connor, Stephen Hymer and others, myself included). The book also sounded an alarm to the movement in Italy: the world was changing fast, the scramble for profits and the attacks on the working class internationally had intensified, and whatever movement was still active in Italy was now isolated in Europe, without Italian militants perceiving their isolation.

By the late 1970s several people on the left, including myself, began paying attention to immigration to Italy from abroad, a social phenomenon that Italy had generally not experienced since the so-called invasions following the fall of the Roman Empire. In the late 1970s immigration was still quite small, though it could not be a vanishing phenomenon. It would develop and become a process involving hundreds of thousands and later millions of people in the next thirty years. Shortly after the April 7, 1979 police roundup of Potere Operaio militants I wrote a short paper, “Alcuni aspetti dell’erosione della contrattazione collettiva in Italia,” on new trends in Italian society, prominent among which I considered immigration.5 It kind of summed up what could be seen already in the mid to late ‘70s. When I delivered it as a paper at a university conference on socio-economic trends in Italy, it was as if it had come from Mars.

DD: What was the significance of the journal Primo Maggio, which you worked on with Sergio Bologna, Bruno Cartosio, Peppino Ortoleva, and Ferdinando Fasce, among others. What was the aim of the journal’s interventions, and did they represent a continuation of the investigations opened up earlier?

FG: Primo Maggio was definitely an opening, particularly in two directions. The more neglected one at that time was how to settle accounts with Bolshevism. Sergio Bologna’s critique of the post-1917 Leninism in the fifth issue of Primo Maggio freed young readers of awe-inspiring Bolshevism.6 The other direction was the United States, and in general the countries that had a long history of capitalism, including of course Germany. These two directions left the post-1917 Communist experiences in Europe and in Asia on the edge. Primo Maggio was suggesting that the world was larger than Italy and that future trends could be detected if the left opened its eyes to an international scenario and, above all, if it was ready to detect movements from the bottom up. The first issue of Primo Maggio came out in mid-1973, shortly after the dissolution of PO, at a time when a small section of PO was not so distant in its perspective from leftist groups that wanted to organize some form of clandestine warfare in Italy. Primo Maggio tried to check the short-circuit rush of many young people to armed guerrilla struggle in Italy.

The perspectives of different groups were already divergent or took different directions at that moment. They diverged even more later on. Since 1971 the publication of il manifesto as a daily by a group of intellectuals who had split from the PCI in 1968 had already launched a constant warning against armed warfare in Italy. To do so, the il manifesto group had to walk a tightrope between the Cultural Revolution in China, and an institutional PCI in Italy. For some time the group underestimated the hostility to the Soviet Union that had accumulated in Central and Eastern Europe. In short, il manifesto still hoped that the Soviet Union could negotiate some presence there with the West. Consequently, 1989 came to il manifesto as a shock. The group and the daily had survived between 1971 and 1989 mostly because they had been on good terms with all components of the Italian left. Now they saw that in Central and Eastern Europe there was no room for good manners. Almost half a continent was turning its back to Soviet methods. There would be no reconciliation there.

Most of those who had been in extraparliamentary groups in Italy were not at all shocked by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Former activists in dissolved groups were not denying that the plight of people left astray after the fall of the GDR was rough. Former members of Potere Operaio in particular had not relied on the Soviet Union, an attitude that accounts for some of the animosity from the PCI against PO militants before and after the arrests of PO people in 1979. Regardless of the PCI, which crumbled down under the ruins of the Berlin Wall, political development was occurring in Central and Eastern Europe, far from decrepit experiences.

As to Primo Maggio (1973-1989), one of the aims of the group of people who initiated it was to bring in young people who had been around the extraparliamentary left since the early 1970s. My involvement was first of all an impulse to help them in the early stages of the magazine. The year 1973 marked also the first issue of Lavoro Zero (October 1973-April 1980), a workers’ paper in Porto Marghera in which I was involved since its first issue. Editing Lavoro Zero with others and daily militant activity was demanding. I could not be in the editorial board of Primo Maggio while I was engaged in Marghera.

Primo Maggio drew me into its editorial board in 1985, after my coming back to Italy, perhaps a gesture of consideration for the work I had been doing earlier, and definitely a call for further editorial sweat on my part. An evaluation so far of the impact of Primo Maggio on political thinking and historical research is to be found in the contributions to a special issue of Primo Maggio that DeriveApprodi publisher has published in 2018. Primo Maggio turned historical research to themes that academic historiography in Italy – and, more generally in Europe – had ignored or neglected: briefly, oral history from the bottom-up, research on the working-class movements in Europe and the Americas, and in particular in the United States, a critical attitude to the historiography still leaning on the PCI, history of ecology, new forms and contents of waged work, to mention a few of its themes.

DD: In 1975 you published an important essay, “Class Composition and U.S. Direct Investments Abroad,” that intended to displace a “victimist viewpoint” – which saw imperialist initiatives as purely active subjects – and advance the workerist perspective on an international plane. (It would seem that your criticisms of the Regulation School likewise want to cut against narratives that assume capital’s autonomy.) What was the relationship between workerism and anti-imperialism? And in what ways could this perspective-shift be helpful still today?

FG: At the time of my essay on class composition and US direct investment abroad (1975) there was no Regulation School. The regulationists emerged later, in the 1980s. In the mid-1970s there was a general understanding that one could write about imperialism only in a kind of vacuum, without real human forces acting in conflict. It was all Robinson Crusoe and no Friday, as Stephen Hymer had begun to say just before dying prematurely in 1974. A helping hand came from the writings by C.L.R. James, George Rawick and Marty Glaberman, and the Facing Reality group in general. We had to look at the limits to capital’s power but we had to name another power in that experience. That power was the working class internationally, in all of its connections. In Luciano Ferrari Bravo’s collection of essays Imperialismo e classe operaia multinazionale (Milano: Feltrinelli, 1975) where my text was featured, there were hints here and there by other authors of some contrasting forces, but they were disparate. I tried to bring the self-activity of the working class internationally into the debate.

The Regulation School has been a group of economists leaning on the moderate étatiste left to turn the clock back to a pre-C.L.R. Jamesian scenario of what has been going on in the relation between the state and capitalism. My essay was an attempt to distance myself from that large amount of economic publications, and to offer a contrast to the magnetic attraction that an abstract entity called capital exerted on the left. I purposefully excluded a discussion of the state. The issue for me was dead labor in the form of capital moving around and being fought by real human beings. It seems to me that in the long run, that exclusion of the state might even be fruitful. The question for us today? My tentative partial answer is another provocative question: will Amazon and Google (just to name two of the giant digital corporations) assimilate the functions of the state or will the state incorporate the vital points of Amazon and Google? I don’t know. A decisive factor for the future will be how ordinary people will transform and leave behind capital’s command on living labor-power.

I was in touch with Bruno Cartosio and Sergio Bologna throughout the 1970s and the 1980s. Both influenced me with the direction and contents of Primo Maggio and with their own writings. What almost interrupted our contacts and my work was the repression starting in 1977, the jailings of former PO members in 1979, and my moving abroad in 1980. By the late 1970s in Italy, the larger perspective was obscured by the debate for or against armed warfare. There were few people with whom one could discuss imperialism or the impact of multinationals, which became taboo words in the Italian press and in the rest of the media for a few years. Still, while abroad I was able to keep in touch with both Bruno and Sergio. Contrary to Italy at the time, I found opportunities for debate in the U.S., particularly with those around Marty Glaberman in Detroit, in spite of the fact that industrial repression had shut down plants and dispersed workers in Michigan. One could still talk to people there who had an international perspective and curiosity. In Italy it was all fear and whispering. In short, in the late 1970s the Italian debate on the real economic trend was dormant or, at least, not very vigorous.

In retrospect, one could say that under the “labor-friendly” Carter presidency the big downturn in the economy was dictated by the Federal Reserve’s increase of the interest rates in August 1979, a move that prepared the ground, or rather, laid the red carpet, for so-called Reaganomics. While there were many brilliant people on the left, few understood the vast anti-labor implications of the August 1979 economic freeze. The illusion they cherished was that the freeze was temporary, and that easy money would come back soon. I tried in vain to convey the idea to friends, that it looked like the Federal Reserve was dead serious. In fact, business and government had long decided to deal a big blow to the working class by starting in the US, and then moving to Europe and Japan.

The left should not have taken the nonchalant attitude it had taken vis-à-vis the right wing of the Republican party since Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1960. That campaign and its defeat should have given observers an idea that it was an early, premature rehearsal for “zapping labor.” I do not ignore that after the New Deal the unions in the U.S. had already been under attack. There had been the Taft-Hartley law, anti-leftist repression, the long battle to smother wildcat strikes. But still in the 1950 and 1960s some voices paid attention to the working people. By the mid-1970s the working class was under the sway of a counteroffensive. In short, The August 1979 Federal Reserve’s freeze was a milestone in a protracted reaction.

Italian exiles from all leftist extraparliamentary groups in the early 1980s discovered an international dimension, particularly in France where most took refuge at a time when French socialists under Mitterrand’s presidency were no longer able to resist the Reagan-Thatcher storm. When living in Italy they had generally neglected the international scenario. Now most of them renewed and expanded their worldview. They were still young enough to form their own opinions about the world. People who had never paid attention to what the colonialist and neocolonialist geography of Europe was, but who could tell the detailed history of a particular Italian factory, now were studying and analyzing the crescendo of that counteroffensive, and the World Bank’s neocolonial blackmail of African countries, a blackmail that was quite evident from the French scenario.

1989 and the Crisis of the Italian Left

DD: What did the situation look like after 1989?

FG: The story of the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 was subjected to different interpretations in different lands. I am of the opinion that its fundamental message was unequivocal: people in the GDR and in Eastern Europe in general claimed some space for their own individuation, which is not simply “individual freedoms.” It is also the necessary space to contrast the dull compulsion that was so evident in the Central and Eastern European countries long before the late 1980s. The most significant shock hitting those who were part of the Bolshevik tradition in Western Europe was the discovery that the individual sphere mattered not only at home but also in Central and Eastern Europe. For instance, PCI-inspired historicism attributed the lack of institutions for freedom there to imaginary customs and traditions. It was as if these peoples were immature for some freedom. That view from the West vanished into thin air in 1989, when ordinary people knocked the ruling parties off the pedestal.

The fall of “actually existing socialism” also revealed a generational divide. As already mentioned, the Western CPs in general but even the older founders of the il manifesto daily in Italy, people who had been PCI militants until 1968, interpreted this loss of a base as a terrible defeat. But the younger generation of people working at il manifesto, some of whom were former PO members, embraced the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

Probably no more than a fraction of the real events is known so far. For instance, not many people know that then-West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl outsmarted the defenders of the Wall by knocking down the Hungarian frontier with Austria in the spring of 1989. It was so early that Kohl secretly paid a billion DM to the Hungarian government to convince Budapest to open its borders with Austria, and let East Germans cross to the West, thus gradually making the Wall a pathetic relic.7 The formal fall of the Wall was a contradictory process, which closed in with fangs: Thus Germany became one country again, while Yugoslavia disintegrated into six countries plus a rump state. However, even just some freedom to migrate to Western countries was immensely significant, as the division between the nostalgia for the old regimes on the one hand and the search for a new process of freedom of expression on the other. The recognition here that also Eastern Europeans were entitled to individuation was a necessary step in the lives of young people who had experienced (or at least heard of) 1968. To some extent the division between nostalgia and individuation is still there, as it is apparent in some areas of eastern Germany. In Western Europe, there were those who had gone through a CP experience and had a nostalgic attitude to “actually existing socialism” while the leftist section of the younger generation saw the fall of the Wall in terms of a chance for renewal, although few had any illusion that big capitalism – first and foremost German corporations – would abstain from taking advantage of Central and Eastern European workers. The price the former citizens of the German Democratic Republic have paid has been high. It was not a reunification of Germany, so much as an annexation by which 85% of the productive sites in the East were taken over by the West.8

As to China, mine is nothing more than a tentative guess. The process of individuation in China may have gone underground but it is continuing. In 1988, 100,000 people inundated Beijing for free speech; and a year later at Tiananmen Square, a smaller aggregation of people claimed the end of one-party rule. At Tiananmen young people were determined to risk their lives for their demands. After 1989 that river has become a myriad of brooks that have not dried up. We should do much more to at least remind people in the West that the invisible movement in China is not stagnant.

Most people on the left in Europe have not cared about Africa since the end of official apartheid in South Africa. They have paid a little more attention to Latin America, but scant attention has been paid to Africa in general since the 1990s. The situation there is going to be an increasingly important subject for debate and action.

Moving closer to Eastern Europe, can we say that in Russia some decent form of government has won? Certainly not. Those who are sincere dissenters in Russia literally have to take their lives into their hands. So again, that seeming immobility probably has legitimated some old leftists in Europe to remain indifferent to the plight of the people living in the former “socialist” republics. A crucial problem in many of these countries, is to find ways to exert basic freedoms and to organize battles around feminism, working conditions, ecology, and land.

In general, when a crisis of identity hits, it hits from within. The ecological movement – most of its trends included – throws a sardonic look at capitalism. This perspective will have a big impact on the people’s confidence that accumulation has enjoyed for the last 400-500 years. If one observes what the young people in the ecological movement are doing, one can see that the endemic trust in accumulation is cracking. Their parents might have been confident in it but young people no longer are. People grow old and are tempted to remain indifferent to the future of the planet, but there will be younger people behind them, sowing doubt within every family. The issue is, on the first level, what to produce and how to produce, and inevitably the question will become: who will do the heavy lifting, and how, and, above all, why? Why should it be young Chinese workers in those mammoth factories under that inexorable work pace? If they were free of those heavy schedules, there would be enough time for people to better understand what is going on. Of course everything could go wrong, and go to ruin. Disasters are always possible, and the right wing’s solutions pose new threats, but at least there would be more time available, time as the material base on which it would be feasible to have not only discussions and public debate, but also some oxygen for everyone to take care of each other in a more collective and less self-centered, isolated way. Isolation is really what capitalism is betting on, these days: isolation will breed quietism, awe, fear, and generate a subservient attitude.

DD: The experience of the journal altreragioni in the early 1990s is little known outside of Italy. What were your aims with the journal? Did you consider this a moment of regroupment for the Italian left?

FG: The idea of a magazine or some kind of new journal had been around since the crisis of Primo Maggio in the late 1980s. It looked like the press of the traditional left was going through an identity crisis. When the PCI folded after the fall of the Berlin wall, there had already been several meetings in Milan about “a piece of paper,” as we called it, where people could write without any allegiance to any party. Some, such as the writer and poet Franco Fortini, saw a new journal as a tool to deny the monopoly of the parliamentary parties on the entire left and to contain the new euphoria of social democrats and liberals turned sweeping free-marketeers. The non-daily periodicals on the left were in crisis while the right was rampant with its private television networks. There were people, including myself, who thought that a new journal – altreragioni – would be necessary to limit the damages of repression in Italy in the late 1970s and 1980s, by transmitting some of the lessons of those years to younger people, and by encouraging them to get involved in a journal that could elaborate a perspective against the rehash of mythical self-interest, light state machines and the invisible hand that would supposedly take care of prosperity worldwide.